Qwertyman for Monday, November 14, 2022

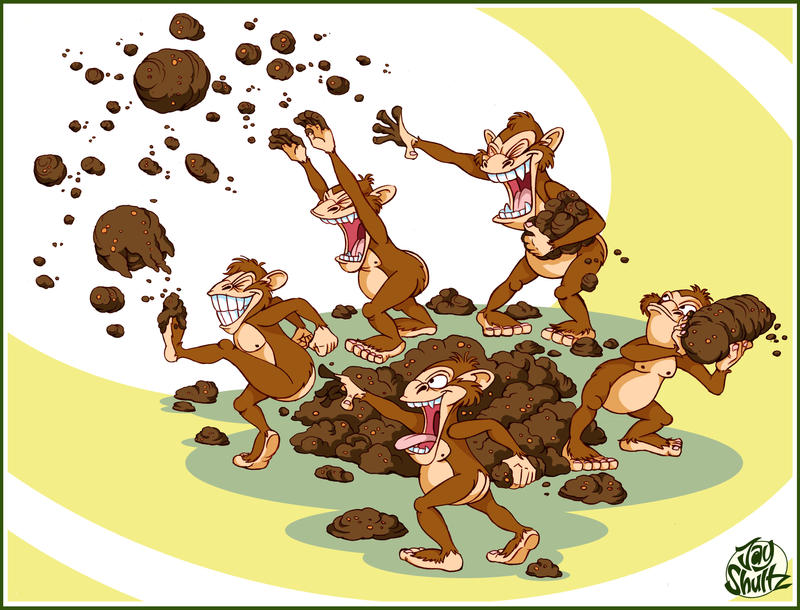

AFTER FOURTEEN straight Mondays of producing what I’ve called “editorial fiction”—make-believe vignettes meant to poke fun at the issues of the day, the prose version of editorial cartoons—I’ll take what will be the occasional break to engage more frontally with a concern of deep personal and professional interest.

Over the next few weeks, the Board of Regents of the University of the Philippines will select the 22nd president of our national university to succeed President Danilo L. Concepcion, whose six-year term ends in February next year. (Let me add quickly, for full disclosure, that I was President Concepcion’s Vice President for Public Affairs until I retired in 2019, and held the same position under former President Francisco Nemenzo in the early 2000s.)

Whether or not you graduated from UP or have a child or a relative there, this is important for every Filipino, because—like it or not—UP produces an immoderate majority of the people who make up our political, economic, and social elite. Its leadership, therefore, is a matter of national consequence. Since its birth in 1908, UP’s alumni roster has counted presidents, senators, congressmen, CEOs, community leaders, artists, writers, scientists, and, yes, rebels and reformers of all persuasions.

There are six candidates on the BOR’s ballot, some of them, to my mind, more qualified—beyond what their CVs say—than others. The Board of Regents has eleven members—the CHED chairman, the incumbent president, the chairs of the Senate and House committees on higher education, the alumni regent, three Malacañang appointees, and three so-called sectoral (faculty, student, and staff) regents; it will take six of them to elect the next president.

Whoever that choice is, he will be certain to have a challenging six years ahead, especially considering the present political regime, which he will have to contend and to some significant extent work with. UP remains dependent on the national government for its budget, for which it has to make its case before Congress every year, like any other agency.

Prickly issues will face No. 22. There’s been a lot of loose talk lately about UP’s standards supposedly falling, with too many cum laudes graduating even as its international ranking has reportedly dropped. Indeed these should give rise to public concern, but there’s more to it than meets the eye, and UP’s level of service to the nation (think PGH in the pandemic) hasn’t flagged.

Historically, the relationship between the Philippine president and the UP president has been a testy if not an acrimonious one—most notably that between Quezon and Palma—because of the university’s role as social critic. But Malacañang now has much to do with choosing the latter through the power wielded by administration representatives on the BOR. What the Marcoses will do with UP remains to be seen; will the next UP president, for example, be given free rein to pursue the martial law museum project that’s already been approved for construction? It may not be the most important item on the agenda—more support for research and faculty development should be, if we want to shore up our ratings—but it will be strongly indicative of how the Palace will deal with Diliman.

What I’ve observed is that the role of the UP president has greatly evolved since Palma’s time. While many of us would like to see an ideological firebrand at the helm, UP is a broad and diverse community whose survival and growth will require keen diplomatic skills to negotiate between the university’s external and internal publics. (And yes, even firebrands can do that, against all expectations; Dodong Nemenzo did.) University presidents worldwide have increasingly been more of resource generators and managers than thought leaders—perhaps boring, but they deliver the goods. What’s important is for them to be able to practice and defend the academic freedom that also allows the university to become the best it can be. I pray our regents will bear that balance in mind in its deliberations.

ALSO, A word on my chosen approach to editorial commentary. I know that some of you can’t make heads or tails of my fictionalized renditions of our political and social culture, but I think you will, with just a little more effort. Maybe it’s the literature professor in me, but I believe readers should be challenged to figure out the sense of things, and not just have it served to them on a platter.

We’ve fallen into the groove of letting others reach our conclusions for us, so all we need to do is nod affirmatively. Whichever side of the political fence you’re on, that only contributes to sloppy, second-hand, copy-paste thinking. In my pieces, I try not focus on just one person or one target—other and sharper columnists can do that. I’m more interested in the culture of our politics—in the way groups of us think and feel about what’s in our best interests—and in our complicity in bad governance. Sure, we have rotten eggs in high public office—every administration has had them. At this point, I’m much less bothered by the fact that we live in a world of despots than by the fact that we (or many of us) put them there, we keep them there, and we just pinch our noses when they stink.

Another columnist (who actually writes wilder fiction than me and my feverishly imaginative friends) even complained that fiction has no place in the op-ed page. Excuse me? All fiction is opinion, and always has been; the critical commentary of fiction even preceded journalism. In earlier times, our op-ed pages even offered poetry—political commentary in verse—at a time when our poets were patriots, and our patriots were poets. Sadly those times and those exceptional commentators are gone, replaced by hacks producing not only dishonest and soulless but dishwater prose.

I’m not a poet, so the closest I can get to that is fiction, which pretends that some things happened that didn’t (but then again, in another sense, really did—and that’s what some readers find confusing). One thing I must confess I do like about fiction is that, unlike factual commentary that readers today tend to forget after a week, a good story sticks around. Sadly for its implicit targets, fiction is forever. You can shoot me dead, but my work will survive me—and, for that matter, you.