Penman for Monday, Dec. 10, 2012

Penman for Monday, Dec. 10, 2012

A FEW weeks ago, in Melbourne, I had the pleasure and privilege of speaking before a global audience of experts in and practitioners of nonfiction—that broad branch of writing that straddles everything from journalistic reportage, history, and philosophical essays to personal memoirs, travelogues, and cookbooks. I gave one of the four keynote addresses in that three-day-long Bedell Nonfictionow Conference; the other speakers were David Shields, on collage and appropriation; Helen Garner, on the central place of the interview in nonfiction; and Margo Jefferson, on the boundary between criticism and nonfiction. I chose to take a less technical and more social tack, and talked about why, more than ever, there’s a need for nonfiction in this age of the Internet, particularly in places off the global literary centers like the Philippines.

I wasn’t alone in representing the Philippines and its literature. Lawrence Ypil, one of our brightest young poets who’s doing a second MFA at the University of Iowa, this time for nonfiction, spoke about using family photographs to solve a mystery, and also introduced the work of Resil Mojares and Simeon Dumdum Jr. from his native Cebu. Longtime activists Bonifacio Ilagan and Marili Fernandez-Ilagan discussed the political possibilities of nonfiction in print, film, and theater; Boni also gave a comprehensive overview of recent political nonfiction from the Philippines. Their talks provoked much interest, and reminded me of just how far ahead of the curve our writing is in many ways, despite the obvious obstacles to writing in a society that doesn’t seem to value books much.

So I used my keynote as an opportunity to reintroduce contemporary Philippine literature to others, highlighting our work in nonfiction, particularly that of the late, great Nick Joaquin. Below is the full text of that 40-minute talk (because of space limitations, I was able to provide only an excerpt for the newspaper column version of this piece):

Thank you all for this great honor of having me as one of the keynote speakers for this conference, and for this opportunity to introduce another literature and another literary experience to a global audience, from which we Filipinos have been largely removed. And who, exactly, are we Filipinos? Just two days ago, a Gallup poll revealed that Filipinos were the most emotional people on the planet. We laugh and we cry with equal facility—so don’t be too surprised if this talk descends from the sublime to the ridiculous within a paragraph of each other.

This being a keynote, let me assure you that this talk will be about more than our domestic literature, and that it will connect to the greater issues of nonfiction in the world. But I have chosen to begin on a point of disconnection, from the periphery, because our vagrant experience presents some interesting possibilities for looking at how nonfiction—if not literature itself—has served self and society outside of the West.

Indeed, these past few years, I’ve traveled around various literary conferences around the world with a stock speech titled “Why You’ve Never Heard of Me,” by way of addressing the relative obscurity in which the Filipino writer has labored—even and especially in the company of our fellow Asians such as the Chinese, the Japanese, and the Indians who have understandably gained much greater international attention and prominence.

In sum, my thesis is that we Filipinos don’t write enough novels, and the novel has been the ticket to literary fame and consequence in 20th century publishing. It also hasn’t helped that, as a former colony of Spain and the United States, we are out of the Commonwealth loop. We no longer write in Spanish, and as for our writing in English—a thriving, century-old literature—the Americans (with the notable exception of Robin Hemley) don’t quite know how to receive it, despite its troubling familiarity, like the bastard child who suddenly appears at the door with an expectant smile. We also have a robust literature in our other national and regional languages, but again they hardly connect to the other native literatures of Southeast Asia, in gatherings of which the non-Bahasa-speaking Filipino has often been the odd person out.

That’s all the more strange when we consider the Filipino diaspora which—like that of the Indians, the Nigerians, and many other ambulatory nationalities—has taken our workers all over the planet. We are you maids, your nurses, your sailors, your entertainers. One-tenth of our population of over 90 million people now live and work overseas, in places as remote to us as Iceland, Angola, and Syria, providing not just the foreign remittances that keep our economy afloat but also a wealth of material for our literary imagination. Indeed it often takes the literary imagination, more than journalistic reportage, to sort out these experiences of dislocation.

But why even go abroad for alienation? If there’s anything colonialism does to the colonized, it’s to leave behind two states of mind, often manifested in two or more predominant languages, one of which represents the colonial elite. That’s American English in our case, and while it’s given us a global edge in the BPO or call-center industry—in which we now rank second, next only to India—it has produced no comparable literary dividends, with our literature in English trailing far behind India’s, and even behind translations to English from the Chinese and Japanese, in the attention of the world.

Thus we represent an insular experience. But like exotic species which—after a geological point of separation—have survived and mutated on their own in some tropical plateau or some literary Galapagos, literatures like ours can be interesting and useful objects of study, because they manifest both fundamental similarities to and striking departures from the biological mainstream. They speak back to the mainstream, as I am speaking today, and offer up a mirror—perhaps a somewhat distorted or distorting mirror—in which others can see versions of themselves.

Our insularity has resulted in some interesting courses of evolution. Given the absence of a market for novels, we have developed our strengths in poetry and the short story. Given further that there is no money to be made either in poetry or the short story—but also that these genres require little material investment—our writers have focused on producing the best art they can, rather than on satisfying a market (and there was, arguably, a market for these in our newspapers and magazines of the early 20th century, when they were part of the entertainment mainstream).

In the case of Philippine nonfiction, curiously enough, more titles have been emerging over the past 20 years—memoirs, biographies, histories, essays, travelogues, cookbooks, and motivational materials for business and religion. Most it not all of this production has been in English rather than in the national language, Filipino—not surprisingly, since books are expensive and considered non-essential items in a country still largely poor, and the people who can buy books at and for their leisure speak and write in English. (Parenthetically, this introduces another interesting element for further thought: if translating language means inevitably translating experience, what goes on in nonfiction in a foreign or borrowed, and especially a colonial, tongue? Whose stories tend to get told, and how, from what perspective?)

There has also been a perceptible rise in enrollments in courses and workshops for nonfiction, seen by many—correctly or otherwise—to be a less formidable and more accessible entry point to writing than fiction or poetry.

The rising global popularity of nonfiction is manifest in the region. A quick glance at the recent titles taken up by the Hong Kong-based Asian Review of Books will reveal a clear preponderance of nonfiction, covering such diverse topics as the undercities of Mumbai, Christianity in Communist China, the Thai monarchy, the Amritsar Massacre, the Jewish community in Shanghai, and Japanese ninjas. Not surprisingly, much of this nonfiction deals with China and India, being both the largest sources of and markets for such work. There is great interest in the West in these two countries, as well as in Japan and Korea, because their economies are umbilically tied to those of the West.

But let me go beyond money and markets, and talk about the necessity for nonfiction in less familiar and less mediagenic countries such as ours.

To state the obvious, nonfiction provides an alternative to fiction and of course to itself. In the first instance, I don’t simply mean the choice the reader faces at the bookshop at any given moment between buying a novel or a book of essays, but as a means to appreciating the truth, in which everyone is presumably interested and invested.

That truth can be particularly elusive in a country and society where there has been a longstanding tradition of suppressing it—in our case, the nearly two decades of the rule of Ferdinand Marcos, carrying over to his successors, one or two of whom turned out to be even more adept than Marcos in kleptocracy and in hiding the truth.

In this experience we Filipinos can hardly be alone, given the emergence and in many cases the continuing rule of autocrats, despots, and demagogues around the world, from Asia and the Middle East to Africa and Latin America. Personal accounts and testimonies are important in such places where an “official version” of events is often promoted, if not enforced.

While fiction might best capture the grotesqueness of life and the absurdity of the truth in many of these places—and I’ll get back to this later—it is nonfiction that bears the burden of presenting the facts on the ground, often at great risk to the author and even to the reader.

It was just a little over a week ago when PEN International marked the Day of the Imprisoned Writer—an issue I could personally relate to, having been imprisoned for seven months in 1973 at age 18 not for writing any earth-shaking novel but rather political flyers and such ephemera. Among those on PEN’s list of “focus cases” was Ericson Acosta, a young poet and activist who had been writing and filing reports on human rights abuses in the Philippine countryside. He has been held without trial since February last year—ironically, under the regime of President Benigno Aquino III, whose family has been canonized for its espousal of civil liberties.

The authoritarian State not only seeks to stifle the truth: it is an active and imaginative producer of fiction. In the Philippines, this was never more palpable than during the long years of martial law, from 1972 until the expulsion of the Marcoses—at least for the time being—in 1986. Let me share a few stories in this regard.

In 1964, just before he first ran for President, Marcos commissioned Hartzell Spence—an American author and editor of Yank magazine, who contributed the word “pinup” to the vocabulary—to write his biography, titled For Every Tear a Victory (later reissued as Marcos of the Philippines), of which a film version was later made. These biographies touted Marcos’ wartime heroism, for which he supposedly received 27 medals, thus becoming the most highly decorated soldier of the war on the American side. Most of these decorations were subsequently proven to be fake. Spence reported that Marcos sustained wounds from singlehandedly engaging 50 Japanese soldiers in a gun battle, a claim Newsweek later disproved. Marcos also claimed to have led a guerrilla force of more than 8,000 men, which the US Army dismissed upon investigation as “fraudulent” and “absurd.”

There was no doubt that Marcos was a brilliant fellow—he topped the bar examinations in 1939, having reviewed for the exams while in prison for allegedly shooting his father’s political enemy at night between the eyes; the young Marcos had been a sharpshooter with the ROTC, and was the natural suspect. He defended himself before the Supreme Court and was acquitted, and the legend was born. Indeed, it was easier to create and to promote the myth because the known facts in themselves seemed incredible enough.

Sometimes the myth was not about himself, but about the nation and its prehistory. In 1971, one of the biggest stories to rock the anthropological world was the discovery of the Tasaday, supposedly a Stone Age tribe that had somehow survived in the Philippine South in benign innocence, well into the 20th century. They made the cover of the National Geographic and were hailed as if Adam and Eve themselves had stepped wild-eyed out of Eden, until skeptical parties spoiled the fun by decrying the Tasaday as an elaborate hoax. As chronicled by Robin Hemley, more responsible investigation has since established that the truth very likely lay somewhere in between—that the Tasaday were neither quite that ancient nor that synthetic, but had lived largely by themselves for a long time. The Marcos government, however, felt deeply invested in validating the notion of a lost tribe, as it seemed to extend the arc of development even farther back, as if to say, “Look how far we’ve come.”

To make sure that the future got things right, in 1977, Marcos published a multivolume history of the Filipino people under his own byline, titled Tadhana, or “destiny,” for which he had actually commissioned some of the country’s most eminent historians.

To reach beyond the range of books, the Marcoses ventured into film. One of the most memorable projects I’ve ever worked on—if only because of its intentions—was an abortive film epic conceived and commissioned by Imelda Marcos, circa 1978, involving the production of a four-hour extravaganza on Philippine history from Ferdinand Magellan to Ferdinand Marcos. This was to be the Marcoses’ version of Hitler’s Triumph of the Will. But instead of having just one Leni Riefenstahl, Imelda wanted eight of the country’s top film directors and their scriptwriters to stitch the opus together, dividing four hundred years of Philippine history among themselves into a half-hour segment each.

As it was the height of martial law, there was no saying no to the Madame, and film director Lino Brocka took me along, as a 24-year-old rookie scriptwriter, to a meeting with Mrs. Marcos in a State guesthouse near the presidential palace where, over bottomless cups of coffee and increasingly crumbly cupcakes, she lectured us for at least six hours on how to make a good movie. The meeting lasted so long that we had to be issued special passes, because a 10 pm curfew was in effect, and we staggered home around 2 am. The movie was done, but for some reason was—and I should probably add thankfully—never shown and never seen in its entirety, not even by its makers. It remains one of the great mysteries of mythmaking under martial law—all those reels of footage devoted to the historical inevitability and apotheosis of Marcos, which must now lie in a warehouse somewhere in Manila and have themselves become historical relics.

But this kind of mythologizing did not begin nor end with Marcos, and it would be naïve to think that other Filipino leaders did not avail themselves of the power of fiction—or, otherwise, the power of silence.

Let me point out here quickly that while repression remains a very real threat in our society, Philippine literature and journalism are wonderfully wanton—we have no sacred cows, no taboos. We feel free to write as we please, if only because we suspect, with some justification, that the government is functionally illiterate, and doesn’t give a rat’s ass about what you say in your obscure novel or inscrutable poem. But this doesn’t mean that there’s no political backlash, when someone upstairs does read or misread your report in the newspaper, the magazine, or online.

Those genres tell us something, by the way—that, at least in the Philippines, nonfiction is a far riskier enterprise than fiction. Statistics kept by the international Committee to Protect Journalists show that 73 Filipino journalists have been killed since 1992. So far, no novelists or poets have figured on the death list.

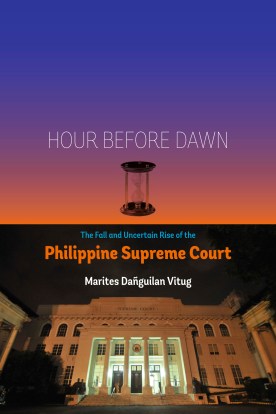

Some of our journalists eat death threats and libel suits for breakfast. One of them has been Marites Vitug, a groundbreaking magazine editor and investigative reporter whose two books on the Philippine Supreme Court—and the shenanigans within, which culminated in the recent impeachment of the Chief Justice—have become two of the hottest nonfiction titles in town. I copyedited both books—doing the first one anonymously, asking my name to be left out of the acknowledgments—not necessarily because I feared for my life or freedom, but because I knew that the book would result in a libel suit which would be more an annoyance than anything; I had many foreign engagements lined up and a libel suit (two of which I’d already faced myself, one from the former President’s husband) would mean that I would have to secure permission from the court even to spend, say, a weekend in Hong Kong. Sure enough, Vitug got slapped with a libel suit and a death threat, which thankfully went nowhere.

But speaking of journalists, let me introduce a name that will be unfamiliar to most of you, by way of celebrating the indigenous explosion of creative nonfiction around the world.

Born in 1917, Nicomedes Marquez Joaquin, better known as Nick Joaquin, was, by popular acclamation, the greatest Filipino writer of his generation, a man who effortlessly straddled the worlds of street-level journalism and highbrow fiction. He practiced New Journalism well before the term was coined, and wrote true-crime fiction well before Truman Capote put it on the publishing map. To Nick—and to use his own words—journalism was “literature in a hurry,” and Nick Joaquin seemed to be in an awful hurry, producing an average of 50 feature articles a year, according to his biographer. He wrote these under a pseudonym that was also an anagram of his surname, Quijano de Manila. He would also write some of the most memorable Filipino short stories and plays of his time, in an English inflected with the exuberance of the Spanish he also knew and loved, but it was his unique reportage that made him accessible to a broad public. He took on all subjects—politics, crime, showbiz, and sports.

According to critic Resil Mojares, “He raised journalistic reportage to an art form. In his crime stories—for example, ‘The House on Zapote Street’ (1961) and ‘The Boy Who Wanted to Become Society’ (1961)—he deployed his narrative skills in producing gripping psychological thrillers rich in scene, incident, and character. More important, he turned what would otherwise be ordinary crime reports (e.g., a crime of passion in an unremarkable Makati suburban home or the poor boy who gets caught up in a teenage gang war) into priceless vignettes of Philippine social history.”

I’m going to read you a few short paragraphs of his prose, just to suggest his treatment of his material, and also his language:

In “Flesh and the Devil,” published in January 1962 in the Philippines Free Press, Joaquin introduced a story of white slavery by harking back to ancient mythology:

Proserpine, in classic myth the daughter of the earth mother, was kidnaped by the lord of the underworld and carried to hell. Rescued and brought back to earth, she found herself alien to its light and flowers; half of her heart had turned dark; she had eaten of hell’s pomegranates and must ever partly dwell in shadow.

The pomegranates of hell were news last week in the story of four girls who said they had escaped from hell after several months of an evil bondage; their flesh had been made merchandise. Three of the girls are 19 years old, but the fourth is a child of 15, and her name is Proserpina.

But he could be as hard-boiled as they came. In “The Mystery of the Murdered Bigamist,” published in May 1961, he reported on the discovery of a corpse:

He had been stabbed eight times in the left breast, his throat had been slashed, and he had been hit so hard in the face his left eyeball had sunk. He had been trussed up with a rope, his hands and feet bound together behind him, and he had been stripped of his wallet, watch, ring, and shoes…. In the ditch where he was found, the police found the bloodstained fragments of a letter in Pampango. The writing was almost illegible, but the signature was clear: Felino.

And always, Joaquin sets the piece in its larger context, as the enactment of an ageless drama. Reporting in 1963 on the bloody assault of a government office by private security guards gone rogue who had axed the skulls of their victims—also security guards—he would write that:

In the August 26 robbing of the Rice and Corn Administration’s main office in Manila, the security-guard culture, long a-ripening, has burst into saga and epic. The eyer is now the eyed, and the figure that has so long lurked at the edges of our consciousness has moved into the center of our attention. We stare at the symbol of our unsafeness.

Security guards were the victims, security guards were the villains… The tragedy happened within a special sphere, among an esoteric society or knighthood of men bound by their own codes, their own private rituals, a shared lore…. A couple of the invaders had been false to the code of the brotherhood and had been ousted, and returned in stealth and were let in, because they knew the secret words and rites.

Joaquin goes on to chronicle sundry acts of mayhem and mésalliance: the murder of a movie star’s delinquent son; the affair between a Filipino ambassador and a German baroness; an abortive shooting of an actor who later became President of the Philippines. Despite his many awards for his fiction and drama, he never considered journalism beneath him. In 1996, he said that “Journalism trained me never, never to feel superior to whatever I was reporting, and always, always to respect an assignment, whether it was a basketball game, or a political campaign, or a fashion show, or a murder case, or a movie-star interview.”

In 1977, his best journalistic pieces were compiled in several anthologies, under the titles Reportage on Crime, Reportage on Lovers, and Reportage on Politics, and eventually these selections grew to more than ten books; in addition, he wrote histories, almanacs, and a dozen biographies.

I brought up Nick Joaquin (who died in 2004) not just to introduce a name, but also to show that the New Journalism and creative nonfiction were laying down native roots in other parts of the world outside of the West—certainly not only in the Philippines—before we knew them by these terms. Joaquin’s Free Press pieces, which began in 1957, antedated Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, which was published in 1966. Of course Capote never claimed to have invented the true-crime genre, and neither did Joaquin, and more thorough investigation will easily turn up far earlier examples from all around the world.

Indeed, we are often referred back to the Scotsman William Roughead, who began attending trials at age 19 and, in 1913, published the first of many collections, Twelve Scots Trials, which he called “adventures in criminal biography.” It’s instructive that Roughead lamented his publisher’s choice of that title, which he thought was too dry. He said that “Trials suggested to the lay mind either the bloomless technicalities of law reports or the raw and ribald obscenities of the baser press.”) You’ll note that in this desire to eschew “bloomless technicalities” and “raw and ribald obscenities” lies the fundamental impulse for creative nonfiction.

The highest crimes, of course, are often perpetrated by the State, and this again is where the greatest value of nonfiction lies, in unraveling the truth where the outcome could affect the lives and fortunes of millions. Sometimes the most significant outcomes are no more immediate and practical than an understanding of the past, especially when alternative histories face off against each other.

This is where nonfiction competes against itself, one version versus another. We often speak of nonfiction in the same breath that we say “the truth,” as if nonfiction and the truth were interchangeable, but this is something that everyone in this conference should know cannot always be so. Nonfiction is, in a sense, a process rather than a product, a way to establishing certain verities most of us can accept or agree with or recognize, albeit with some resistance.

Most notably, nonfiction is an arena for competing histories or interpretations of history. This again is particularly important where the formation of a people’s self-image is involved, especially in a colonial or postcolonial context.

Traditional historians, for example, have viewed and represented the uprisings of poor peasants in the Philippines as the epileptic seizures of cultist fanatics, rather than legitimate and inevitable revolts of the feudal oppressed. The communist guerrillas who fought the Japanese in the Second World War and struggled on against the American-supported postwar regime—much like the Vietnamese resistance—were presented as power-hungry troublemakers and stooges of the Soviet Union and Red China, disregarding their deep nationalist and anti-imperialist orientation.

These histories and their alternatives continue to be written in my country and, I’m sure, in yours. In my own nonfictional work, I’d like to think that I’ve contributed to this conversation through the biographies and institutional histories that I’ve been writing, about which I’ll say more in this afternoon’s panel discussion on nonfiction from the Philippines. Nonfiction is even more essential in this age of Facebook and Twitter, when every event is deemed newsworthy within five seconds of its occurrence, for even the worst—or some would say the best—of gonzo journalism bears some of the composure and the composition of art.

Nevertheless, the argument can always be made that sometimes the best response to fact is fiction—not the fiction of the State, but the fiction that emanates from deep within the individual’s heart and conscience, bodied forth by the free imagination. Fiction—especially the kind of realist, pre-postmodern fiction that still predominates in Asia—is relentless in its effort to make sense of events and of the characters who impel them. Our narratives tend to be straightforward, transparent or at least translucent rather than opaque, trading cleverness of presentation and virtuosity of language for what is seen—or hoped to be seen—as honest, heartfelt storytelling, the object of which is the understanding of character and the improvement of community.

Our national hero Jose Rizal was an excellent polemicist who scored the abuses and effects of Spanish colonial rule in one essay after another—but it was his two novels from the 1880s, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, that captured both the obviousness of the need for some kind of revolutionary action and yet also the complexity and difficulty of making this choice. His farewell poem, supposedly written in his prison cell on the eve of his execution by firing squad, is impressed in the national consciousness.

Under martial law, when our presses were shut down and all the newspapers and magazines were producing hosannas, it was poetry, fiction, and drama that took up the fight—slyly, stealthily, employing such disguises and devices as we knew would escape the regime’s eyes and yet catch the public’s. In 1983, when Sen. Ninoy Aquino returned from exile in the US, only to be gunned down by an assassin at the airport—thereby precipitating a chain of events that would ultimately lead to Marcos’ downfall and departure—my reaction was to write not an essay, but a novella set in 1883, with a revolutionary agent returning from Hong Kong being assassinated on his homebound voyage.

I’ve also written a novel about those years, about growing up under Marcos and about our complicity in the whole project; but one of these days I’d like to embark on my dream project, which is an oral history of our martial-law experience through the eyes of various protagonists from all the sectors involved—the resistance, the government, the military, the businessmen, the citizens.

And then perhaps we will understand why, 40 years after they virtually proclaimed themselves rulers for life over one of the happiest and yet also the most dolorous people on the earth, and even long after the downfall and the death of their patriarch in 1989, the Marcos family remains staunchly embedded in our political firmament, with Imelda Marcos in Congress, her daughter Imee in the governor’s mansion, and her son Ferdinand Marcos Jr., now a senator, being groomed for the presidency. It was as if martial law never happened—and to many Filipinos, especially the young, it never did.

Simply put, the full story of this most traumatic episode in our modern history has yet to be told. Most of us never knew what happened behind the barbed wire; most of us never understood that the prison began well before the barbed wire, and extended into our homes and our subconscious. We cannot remember what we never knew, and we can never learn from what we cannot remember.

And this, ultimately, is the necessity for nonfiction—whether it comes in the form of personal memoir or national history, of comic musing or tragic reflection, of travelogue or cookbook, of political polemic or erotic encounter: it constrains us to confront the tangible world, reminds us of our vulnerable, mutable, insurgent physicality, and connects us to a shared past, present, and future. Today it connects me to you and our literature to yours, for which opportunity I once again am deeply grateful.

14.662584

121.070148