Penman for Sunday, March 8, 2026

ASK YOUR Boomer uncles and aunts what period of life shaped them the most, and I’ll bet you anything I have that their answer won’t be grade school, when they were still wetting their pants and wondering why God had to make the other, completely unnecessary sex as well. It won’t be college, either, by which time you were convinced you had the world figured out and that it was obliged to conform to your vision for it.

No, it’ll be that time of our lives that never seems to lose its vividness—not the metamorphosis of one’s body and of its most secret parts, not the quivering thrill of a first kiss or the crushing finality of a rejection, not the ecstasies and the embarrassments. That period, of course, is high school, when we all suddenly grew up, perhaps more in body than in mind.

If there’s any doubt that high school stays with us longest for the rest of our lives, just take a look at Facebook—today the social dominion of Boomers and Gen Xers, deserted by the young ones for Instagram, TikTok, and Discord. Some days you just don’t want to open Facebook because of all the flickering candles you’re bound to see—but you do, anyway, because you’re curious to know if Classmates X and Y are still together, how Classmate Z surely must have botox’ed or AI’d her way to that profile picture, and—on your Messenger or Viber group chat—when and where the next batch reunion is going to happen.

Ah, the high-school reunion! Time to look one’s best, to line-dance and to cha-cha, to trot out the family pictures, to share stories of doing the Camino and of struggling with sciatica, to scan the poundage on one’s old crush, to revive rumors and recriminations dormant for fifty years, to compare maintenance meds, Holy Land tour packages (well, maybe not right now), dermatologists and urologists, and adobo recipes. Most reunions are fun and happy, but not a few end up with someone grumbling, “I knew I should’ve stayed home!” While they say that time heals all wounds, nothing will tear the scabs off like a class reunion.

But then of course it all depends on the class chemistry, and I’m glad to report that mine has been blessed with extraordinary goodwill—maybe because, unlike many alumni batches, we don’t have class officers, we never published a jubilee yearbook (a surefire prescription for High School Horrors Part 2), and we don’t handle money beyond pooling it for impromptu causes.

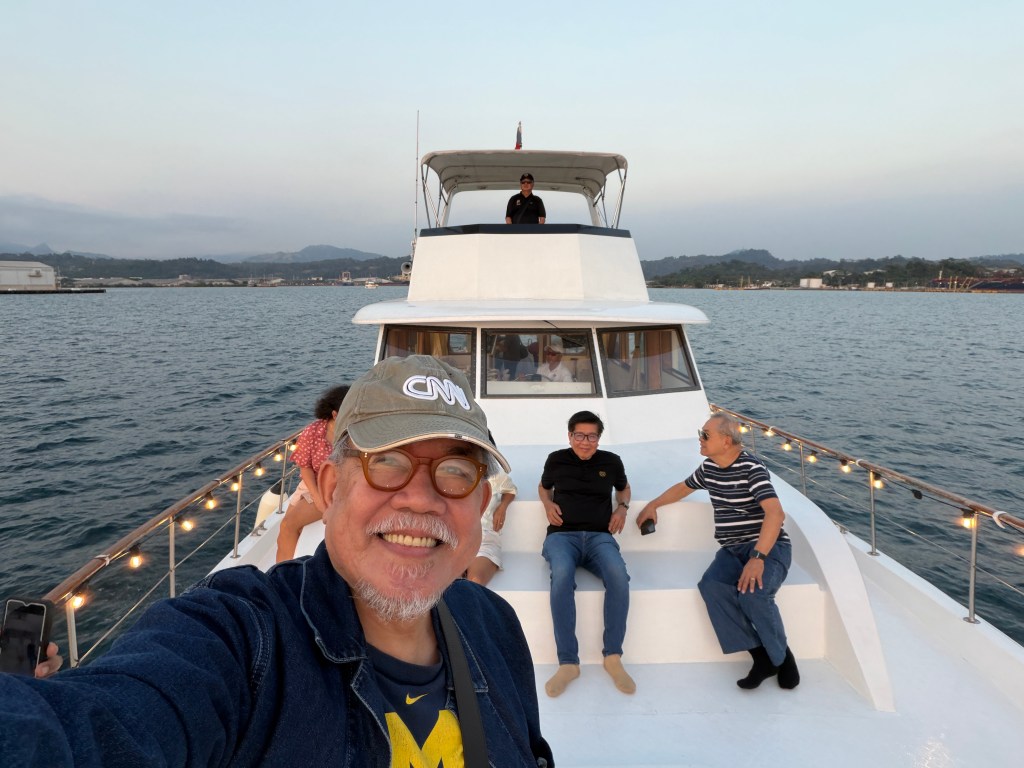

A Subic sortie last weekend with my batchmates in the third cohort of the Philippine Science High School, which we entered in 1966, proved exactly that—get together for fun and food, no great overarching agenda like “Let’s contribute our talents to the betterment of the Filipino future!” (we’ve been doing that for half a century), just spend time chilling out, healing and commiserating, and feeling good to be alive, given that class reunions never really get larger over the years.

If there’s a group of people I know I should speak plainly and humbly with, it’s these guys and gals. If I think I’m smart, well, many of the folks I went to Subic with are certainly smarter—not just in math and science but in the complicated business of life itself (and I don’t mean just in making money—although some of them have done that quite nicely—but in such existential decisions as spending years in the revolutionary resistance and resurfacing to seek social justice in other ways). My friends are engineers, chemists, physicians, managers, educators, pastors, etc., all achievers and leaders in their own ways. But what I appreciate about them is that, in each other’s presence, no one feels obliged to boast about this and that—except perhaps about grandchildren. (Fair warning: if you start a bragging war in this company, you will lose.)

The thing about high school is that forty years down the road you could become a hotshot CEO or a senator, but your classmates will never forget when you were caught caricaturing the teacher or were busted by a crush or locked yourself in the restroom. High-school truths are for life, and you will never outlive your high-school self. That weekend in Subic allowed us to revert to those younger selves, albeit burdened by excess avoirdupois and challenged memory.

My PSHS life was anything but studiously boring. I came in as the entrance exam topnotcher in 1966, almost got kicked out after our freshman year (my grade in English was 1.0 but in Math was 5.0, saved only by a letter of appeal in my best 12-year-old, 1.0 English).

Having gone to an all-boys elementary school, girls were an exciting mystery to me and I became something of a party animal and I jerked, boogalooed, and shingalinged to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, DC5, the Bee Gees, Herman’s Hermits, the Monkees, Spiral Starecase, Procol Harum, the Hollies, Freddie and the Dreamers, Gerry and the Pacemakers, etc. etc. I sometimes came to these dances in a green-and-white striped turtleneck and red-and-green checkered bellbottoms.

We watched “Woodstock,” “The Graduate,” and “Camelot” in the moviehouses of Avenida and Cubao, huddled around a black-and-white TV in a boarding house on Maginhawa Street to watch the moon landing, and marched in the streets shouting “Student Powah!” Our eyes popped when we stumbled on a cache of Playboy magazines in a friend’s house. We bought Lumanog guitars in Raon and followed “Shindig” and “Combat” and “Ang Hiwaga sa Bahay na Bato” on TV. Despite the Vietnam War and the stirrings of activism in our ranks, there was an innocence about the ‘60s that vanished in a poof when the ‘70s opened and the tear gas and the truncheons began to hurt us more than heartbreaks.

That weekend we didn’t talk about anything much more serious than ER and OR survival stories—followed by the familiar catalogue of metformin, statins, saw palmetto, vitamin XYZ—the sort of chatter that would turn Gen Zers catatonic.

A war broke out above our heads and we all sadly agreed that the world we were leaving was worse than the one we entered. We knew something about wars, but thankfully also knew something about having a good time, in spite of time. We went home thinking that indeed, like it or not, high school is forever.