Penman for Sunday, December 3, 2023

A FEW months ago, I had the good fortune of coming into ownership of four watercolors by Juan Arellano (1888-1960), the famous architect of such landmarks as the Metropolitan Theater, the Post Office Building, and the Legislative Building (now the National Museum). Less known to many was that Arellano’s first love was painting, and it was a passion he pursued throughout his life.

My inquiries into the background of my paintings led me to cross paths—initially online—with Juan’s grandson Raul Arellano, who turned out to be an accomplished painter in his own right. Born in Cagayan de Oro, Raul has been based for almost 30 years now in the United States, but he has recently been returning to the Philippines more often. When, one day, he messaged me to ask if we could meet up, I said yes, eager to learn what he could recall of his grandfather but also to get to know him and his art.

I’m by no means an art critic, but my wife Beng (a professional art conservator and watercolorist) and I are museum rats and enjoy both traditional and modernist art, and peek into the local art scene when we can. There’s a lot of brilliance and energy out there to be sure, but also much safe and tiresome repetitiveness from artists who’ve settled on a commercial formula, such that their work no longer exudes emotional power. Many young painters—like their writing counterparts whom I meet at workshops and teach in school—also seem to think that the only worthy subject is death and despair, which invariably means dark canvases devoid of any suggestion of wonder and mystery, let alone delight.

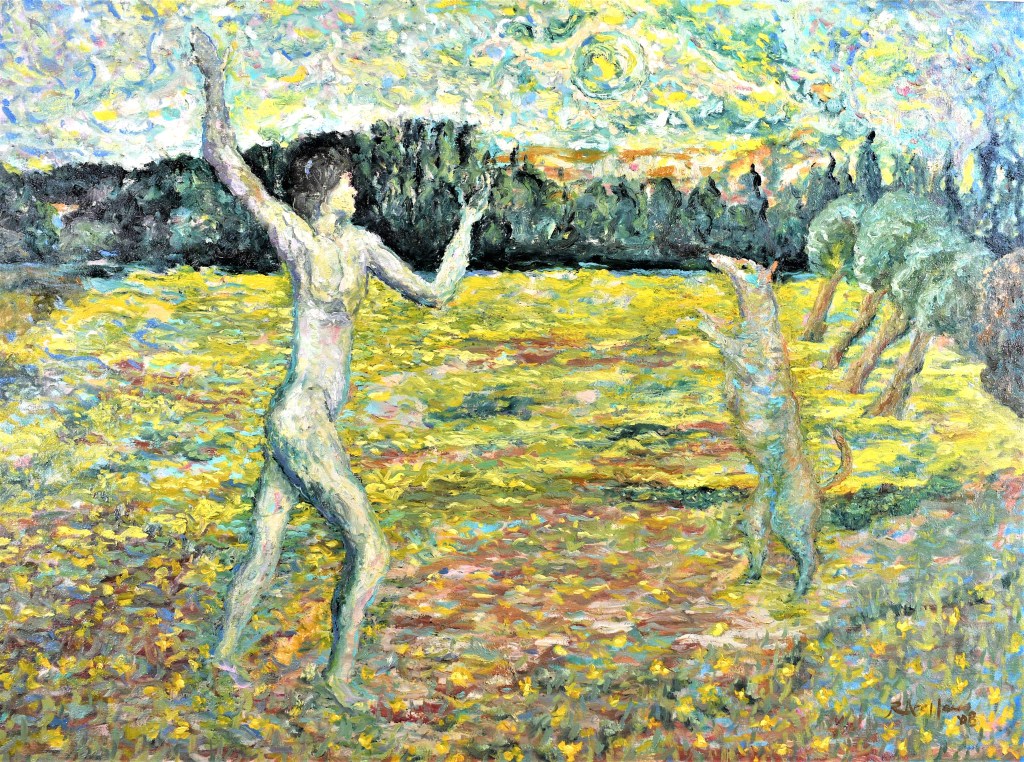

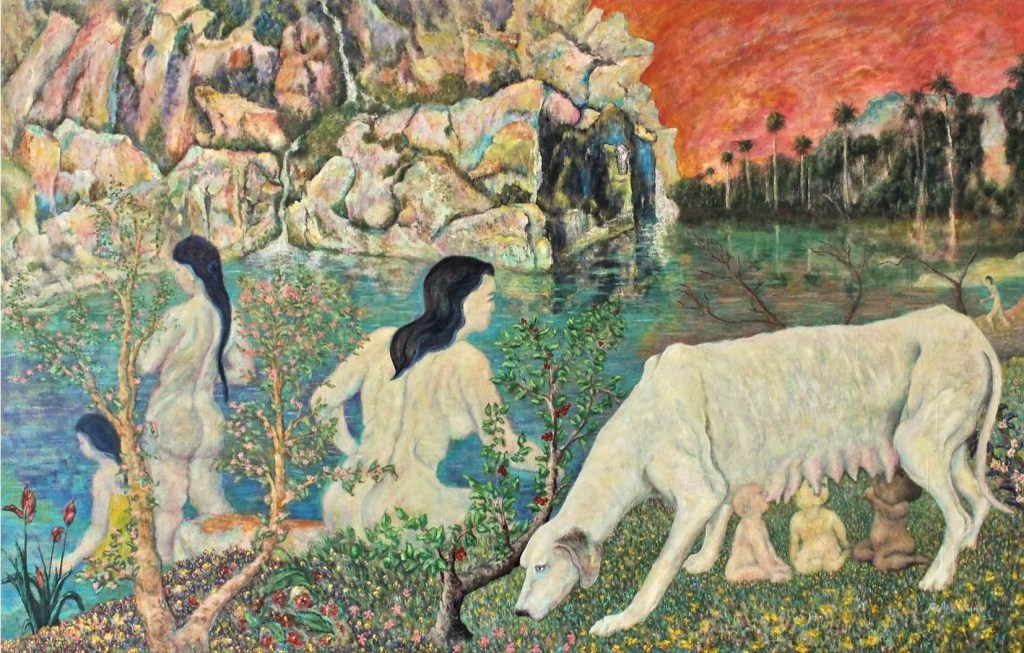

When I saw Raul’s work online, even before we met, what leapt out at me was exactly what I found missing in many others—an element of metaphysical magic, fantastical but relatable, the kind of paintings you want to return to over and over again. I saw flashes of Henri Rousseau, Van Gogh, and William Blake, among others, but it was still all him—not his grandfather, for sure—trying to tell me something I hadn’t really thought much about before.

As it turned out, Raul never met his grandfather, who died five years before Raul was born in 1965 (Raul’s father was Juan’s third son Cesar). All he has of him is a self-portrait—and, of course, a passion for art that runs in the family; his cousin Carlos or “Chuckie,” the son of architect Otilio, was a formidable art patron and collector; Chuckie’s younger sister Agnes remains one of the country’s leading and most imaginative sculptors; Cesar’s brother Salvador or “Dodong” Arellano became a well-known painter of horses and game fowl in California.

Raul’s path to painting was neither straight nor easy. His first great obsession was acting, to the point of becoming a resident actor of Tanghalang Pilipino at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, playing a smoldering Tony Javier in a production of Nick Joaquin’s “Portrait of the Artist as Filipino.” “We were trained in method acting,” says Raul, “and it got to the point that I became so immersed in my character that other people on the set found it unnerving.” He would go on to act in the movies, in the crime drama Akin ang Puri(1996) directed by Toto Natividad, Batang West Side (2001) directed by Lav Diaz, and Himpapawid (2009) directed by Raymond Red. Of his performance in Himpapawid, reviewer Jude Bautista noted that “Raul Arellano as the main character is able to show the frustrations of the common man without going over the top. There is a quiet intensity in his performance.”

That intensity had been brewing in Raul the person for some time, leading to and compounded by domestic problems. In 1995, he took the opportunity to go on a film fellowship at the Art Institute of Chicago. The Midwest was too cold so he later moved to California, and quickly realized what all dreamseekers in LA wake up to: that he had to start all over again at the bottom rung of the ladder. “I swept floors. I learned how to operate a forklift. When the big steel container that you’re lifting comes crashing to the ground, you can feel the jolt running down your spine. I was in a lot of pain, but I kept on. When I left, my boss was very sorry to lose me.”

He set up a business restoring American muscle cars. “I had a Russian mechanic, but I took care of the interiors myself. I specialized in Mustangs—you could show me a Ford screw and I could tell you the year and model it came from. I had a fastback Mustang but my best sale was a Shelby Cobra.” But again another personal crisis blew up and he enrolled in a community college to study painting. He left school once he felt he had learned enough about the history, the theory, and the techniques of art to express himself. “Something in me was always wanting to come out, and I found that release in painting. I had no models or artists I looked up to. I just wanted to express myself, to work from my subconscious. I found that I could work best in a cemetery, because it was so peaceful. I still like working in the open, in plein air.”

The lure of painting proved irresistible. He worked in oils, and one of his favorite paints was lead white, popularly used in the past for its visual qualities and permanence. However, it was banned in the 1970s because of the danger of lead poisoning—a danger Raul was well aware of but embraced. “I found a stash of old paint and bought it all up. I was inhaling it every day and I could feel it doing strange things to my head.”

He returned to Manila every now and then and even resumed acting, but the death of a close friend shook him up badly. “I was all set to come out with an exhibit of traditional, representational paintings, but I was overcome with grief over the loss of my friend, and I just had to express that feeling in my work. So I put all my old work aside and began ‘Crucifixion.’” That work is one of his most impressive and a personal favorite, painted in 2004 at the outbreak of the war in Iraq.

(Image from artesdelasfilipinas.com)

Today Raul spends time in a small farm in Batangas, enjoying quick sketches in the sylvan scenery, and contemplating the possibility of exhibiting in his homeland. With him having gone from peace to pain, from calm to conflict and back again, one can only wonder what new work will emerge from this phase of his life. I find myself wishing for his playfulness to return, but that of course depends on what Raul Arellano is feeling inside.

(More here on Raul Arellano: https://artesdelasfilipinas.com/archives/85/the-art-and-thought-of-raul-arellano-original-)