Qwertyman for Monday, December 23, 2024

IT WAS with deep sadness that we received the news last week of the passing of Francisco “Dodong” Nemenzo, the staunch Marxist, nationalist, and former president of the University of the Philippines. My wife Beng and I are spending Christmas with our daughter in the US and being an all-UP family, we all knew Dodong and were much affected by his loss. Beng had been a student of Dodong’s at UP, and I was privileged to serve under him as his Vice President for Public Affairs twenty years ago. But long before this, I had met him as a student at the Philippine Science High School where his wife Princess taught us History; he came to pick her up in the afternoon in his Volkswagen Beetle whose door was emblazoned with the Bertrand Russell “peace” sign.

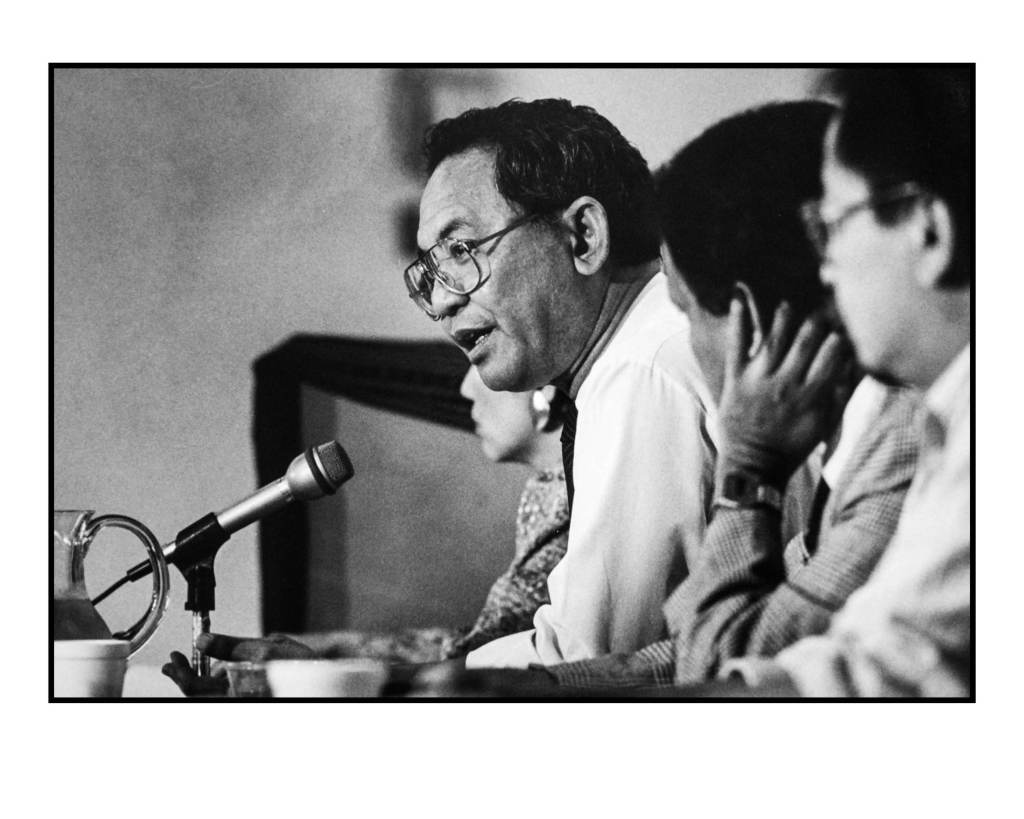

We will be missing the many memorial events that will surely be held in his honor these coming days, so I thought of recalling Dodong in a different way from what most of his colleagues and comrades will be speaking about him. More than ten years ago, I interviewed Dodong for a book I sadly have yet to finish, and he spoke with me about his life before he became the fighting ideologue everyone now remembers him to be. Let’s hear him in this abbreviated excerpt:

“We went back to Cebu after the war. Everything was still in turmoil. I enrolled at the Miraculous Medal School, a Catholic school, and completed my third and fourth grade there. By the time I reached fifth grade, Cebu Normal School was opened so I graduated from there. After sixth grade, I spent a year in the seminary in Cebu. That was my parents’ plan ever since I could remember. I was the only boy among three children, and the eldest. My parents were devout Catholics, and they considered it an honor when a member of the family became a priest or a nun. Since I was an only boy they wanted me to become a priest. I stayed there for only a year, and then I quit. That was probably the beginning of my radicalization. The seminary back then was run by Spanish or Vincentian priests who were supporters of Franco. They looked down on Filipinos and despised Rizal.

“I went to the University of San Carlos. It was a Catholic school but my father was unhappy with the Science instruction. Our science textbook used the question-and-answer method and my father didn’t like that. He examined my notebooks every day and corrected what my teacher said. He got mad when we were taught creationism, and he lectured me on Darwin and evolution. I answered my teacher back and the principal reported me to my father for my heretical tendencies. My father decided to free me from this nonsense and transferred me to the Malayan Academy, a private non-sectarian school that had very good teachers. I finished near the bottom of my class, failing in Conduct and Tagalog.

“I entered UP Diliman in 1953. The rule then was that you were exempted from the entrance exam if you had an average of 82, but my average was around 77 so I had to enroll in a summer institute that was like a backdoor into UP if you passed 6 units there. I didn’t know what course to take. My father didn’t want me to take up Law and wanted me to become a scientist like him, but I reckoned that if I did that, I would always be compared to him and come up short. So I chose a course called AB General.

“The advising line was a mile long. Jose ‘Pepe’ Abueva, a friend of my father’s, passed by and saw me in the queue. He asked after me and I told him that I couldn’t think of a course I really wanted. He tried to sell me on Public Administration, but I didn’t like to serve in a bureaucracy. He said there’d be a lot of opportunities abroad, scholarships, and if I did well I could join the faculty. He had a lot of arguments, but the one that persuaded me was ‘If you join Public Ad right now, I’ll sign your Form 5 right away, and you won’t have to join this crowd.’

“That’s how I ended up in Public Ad. When the dean of Business Administration tried to recruit me and my (Pan Xenia fraternity) brod Gerry Sicat who was then in Foreign Service to go into Economics for our master’s, Pepe Abueva again swooped in and told me to take up an MPA instead, and to join the PA faculty immediately. So I became a faculty member in my senior year, just before my graduation, as an assistant instructor. I probably had the longest title in UP: ‘research assistant with the rank of assistant instructor, with authority to teach but no additional compensation.’ I really wanted to teach, but had no actual assignment. I only took over the classes of professors who went on leave.

“I never joined the UP Student Catholic Action or UPSCA. Well, maybe for one year, but I was never active and then I got out of it. I joined only until I met an UPSCAn named Princess. We always met in Delaney Hall. We were together in the student council. She was representing Liberal Arts, I was representing Public Ad. I joined in 1955, my third year, along with Gerry Sicat, Manny Alba, and Jimmy Laya. I became a liberal and distanced myself from UPSCA.

“I idolized (Philosophy professor) Ricardo Pascual. I was looking for a cause, but these liberals were just fighting for academic freedom with no purpose. It seemed empty. I was under the influence of Pascual for some time, but we had no advocacy. I joined a short course in Social Order at Ateneo on the papal encyclicals on labor. My liberalism and my growing social consciousness merged and I started reading Marx and Huberman on my own, to find out what we were fighting for. There were a couple of professors like Elmer Ordoñez and SV Epistola who according to Bill Pomeroy had already reached that level of consciousness, but when he left they became liberals, they weren’t really organized.” (To be continued)

(Photograph by Rick Rocamora, used with permission)

Dangguit (dried fish) from Cebu, 2008.

Dangguit (dried fish) from Cebu, 2008.