Qwertyman for Monday, September 1, 2025

CAN THERE be any question that the logical next step for cashiered PNP Chief Gen. Nicolas Torre is to run for senator?

The next elections are still three years away; the newly sworn-in senators haven’t even warmed their seats. But the public disgust with the current crop—coupled with Torre’s elevation to hero status—just might create enough momentum and leave enough time for a new wave of Torre-type do-gooders to emerge and coalesce for 2028. The ongoing swell of public outrage against massive corruption in our public works could well become the trigger for a broader and more enduring coalition for good government.

Many remain skeptical of President Bongbong Marcos’ resolve to pursue this drive to its politically torturous conclusion, but such a coalition—which can tap moderate elements from within the administration’s ranks—could force BBM’s hand, being the only viable option to a DDS resurgence in 2028.

Let’s get this clear: BBM may not be our idea of a progressive democrat, and he’s been making the right noises not because he found religion, but because a Duterte comeback will threaten the Marcoses with more vicious punishment than they ever got from Cory Aquino.

Still, it can only be a boon for the middle forces if he helps rather than hinders this brewing tsunami he was at least partially responsible for initiating when he publicly called out those divinely blessed contractors by name. We still don’t know what impelled him to take that extraordinary step, but now that the cat is out of the bag, there’s no pushing it back in, and the people won’t take anything less than decisive action against the greedy rich. You can feel the anger forming out there, the mob right out of Les Miserables taking to the streets, prepared to lynch the next billionaire who flaunts his or her Rolls-Royce umbrella while the poor drown in the floods.

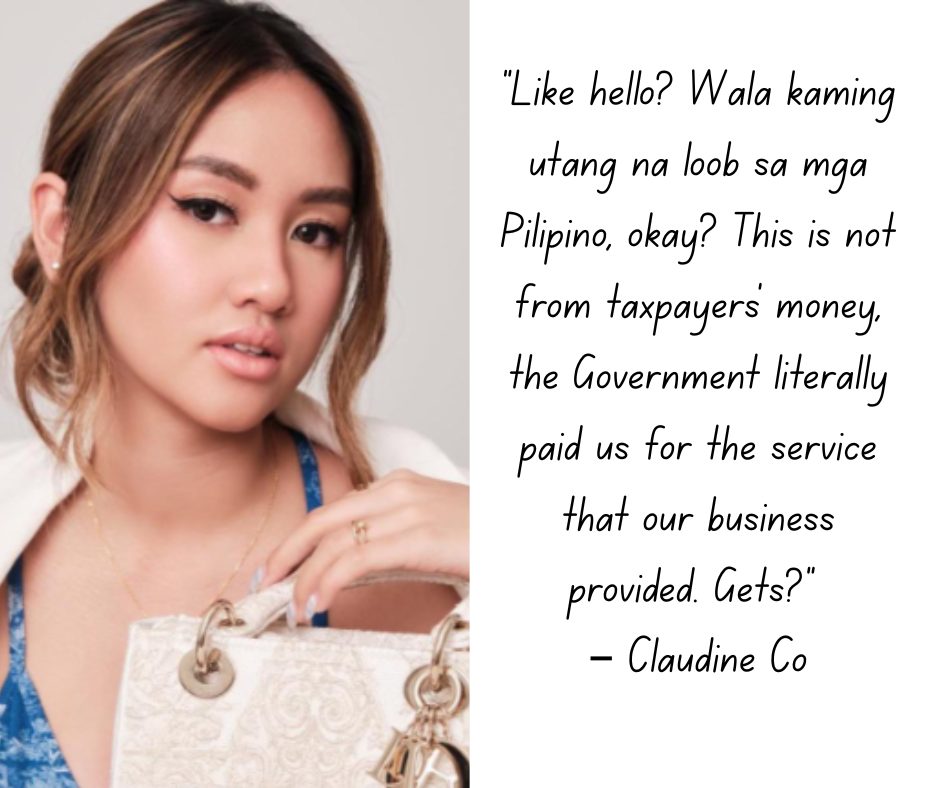

And the message is getting through: ostentation is in retreat, the Birkins and the Bentleys vanishing from Instagram beneath temporary covers until the wave subsides. But will it? How can it, when, trembling and fuming in their fortresses, the objects of our attention continue to manifest consternation rather than contrition? I love it when one of these clueless ingenues, in the midst of the uproar, protests that her family “owes nothing to the Filipino people, because the government paid for services (they) delivered.”

The pretty miss obviously never heard Lady Thatcher, or even saw her meme reminding us that “The government has no money. It’s all your money.” (The full quotation, from a Conservative Party conference in Blackpool in 1983, goes thus: “Let us never forget this fundamental truth: the State has no source of money other than money which people earn themselves. If the State wishes to spend more it can do so only by borrowing your savings or by taxing you more. It is no good thinking that someone else will pay—that ‘someone else’ is you. There is no such thing as public money; there is only taxpayers’ money.”)

This brings us back to Gen. Torre, who showed the kind of resolve we’ve long hoped to see in our leaders by attempting to clean up and straighten out a national police force badly begrimed by President Duterte’s tokhang campaign and by its continuing involvement in such nefarious cases as the apparent murder and disappearance of at least 34 sabungeros.

It seems odd that we civil libertarians should be supporting a general—and one who was ostensibly fired for ignoring his civilian superiors—but this was a man who went against the grain, who employed his authority for the tangible public good in ways that his predecessors (and yes, those civilian superiors) never did. Can people be blamed for thinking that one Torre is worth more than two or three Remullas when it comes to the delivery of public service?

And Torre was right in rejecting the notion of being designated an “anti-corruption czar” in charge of prosecuting corrupt contractors and their cohorts in government. It’s a trap and a setup, for the inevitable failure of which Torre will once again be the fall guy. Does anyone really believe that yet another toothless commission—on top of all the anti-graft and anti-corruption agencies we’ve seen come and go, and all the laws we already have in place—will solve this mess?

The Senate could and should have been that commission, but it’s too laughably compromised to investigate its own, and their brethren in the Lower House. Perhaps we should begin by driving the crooks out of both Houses of Congress, and replacing them with men and women of fundamental virtue, honor, and decency: our Vico Sottos and Heidi Mendozas, among others. And yes, I would even include Baguio Mayor Benjamin Magalong in this list, despite his professed and unapologetic gratitude for President Duterte’s assistance to his city during the pandemic. His loyalty, he says, is to the people of Baguio, and I would rather believe him than all those jokers and poseurs in power who speak of corruption and even of establishing “Scam Prevention Centers” when they should be holding up a mirror to their own faces.

Hmmm, maybe that’s a good idea for our next rally against corruption—let’s bring hand mirrors, the way Hong Kong protesters carried yellow umbrellas to fight for their rights in 2014 and South Koreans lit candles to demand President Park Geun-hye’s resignation in 2016—the “Mirror Movement” to shame public officials and the filthy rich. Mga kapal-mukha, mga walanghiya. Not that we truly expect them to change, but that we expect to change them. Torre for senator!