Qwertyman for Monday, January 19, 2026

I’M WRITING this piece on my 72nd birthday, so I hope you’ll indulge me if I revert to the memory of another January 56 years ago. On the afternoon of January 26, 1970, I milled with thousands of other young students on the campus of the University of Sto. Tomas, the staging ground for a large contingent of demonstrators marching to the Legislative Building near the Luneta (now the National Museum). President Ferdinand Marcos was going to deliver his State of the Nation Address, and a mass action had been called to protest a host of issues, from Marcos’ increasingly authoritarian rule to rising prices, militarization, corruption, and Philippine subservience to American interests.

I had just turned 16, and was a senior and an activist at the Philippine Science High School. But I was no radical—not yet; I stood under the banner of the National Union of Students of the Philippines (NUSP), among so-called “moderates” led by Edgar Jopson, derided by FM as the “grocer’s son” and later to become a revolutionary martyr. Unlike the far-Left Kabataang Makabayan (KM) and the Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK, which I would soon join) who were railing against “imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat capitalism,” the NUSP’s cause sounded much more tangible albeit modest: a non-partisan 1971 Constitutional Convention.

What happened next that afternoon, when both groups of protesters converged at the Senate, would change Philippine political history. The moderates had paid for the rental of the protest mikes and loudspeakers, and wanted to pack up early, but the radicals literally seized the paraphernalia—and figuratively seized the day—launching into a verbal offensive that soon turned physical. Then a young journalist covering the event, Jose “Pete” Lacaba provides the reportage:

“Where the demonstration leaders stood, emblems of the enemy were prominently displayed: a cardboard coffin representing the death of democracy at the hands of the goonstabulary in the last elections; a cardboard crocodile, painted green, symbolizing congressmen greedy for allowances; a paper effigy of Ferdinand Marcos. When the President stepped out of Congress, the effigy was set on fire and, according to report, the coffin was pushed toward him, the crocodile hurled at him. From my position down on the street, I saw only the burning of the effigy—a singularly undramatic incident, since it took the effigy so long to catch fire. I could not even see the President and could only deduce the fact of his coming out of Congress from the commotion at the doors, the sudden radiance created by dozens of flashbulbs bursting simultaneously, and the rise in the streets of the cry: “MARcos PUPpet! MARcos PUPpet! MARcos PUPpet!”

“Things got so confused at this point that I cannot honestly say which came first: the pebbles flying or the cops charging. I remember only the cops rushing down the steps of Congress, pushing aside the demonstration leaders, and jumping down to the streets, straight into the mass of demonstrators. The cops flailed away, the demonstrators scattered. The cops gave chase to anything that moved, clubbed anyone who resisted, and hauled off those they caught up with. The demonstrators who got as far as the sidewalk that led to the Muni golf links started to pick up pebbles and rocks with which they pelted the police. Very soon, placards had turned into missiles, and the sound of broken glass punctuated the yelling: soft-drink bottles were flying, too. The effigy was down on the ground, still burning.”

The January 26 rally and the trouble that erupted would lead to the January 30-31 demos that would prove even more violent, and what would become the First Quarter Storm or the FQS was born. “First quarter” would turn out to describe not only the beginning of 1970 but of the decade itself, as the start of 1971 would prove just as incendiary, with the establishment of the Diliman Commune (and of course, now as a UP freshman, I was there). It seemed that the entire country was politically on fire, with protests mounting by the week, and it would all culminate in what everyone predicted: the declaration of martial law in September 1972.

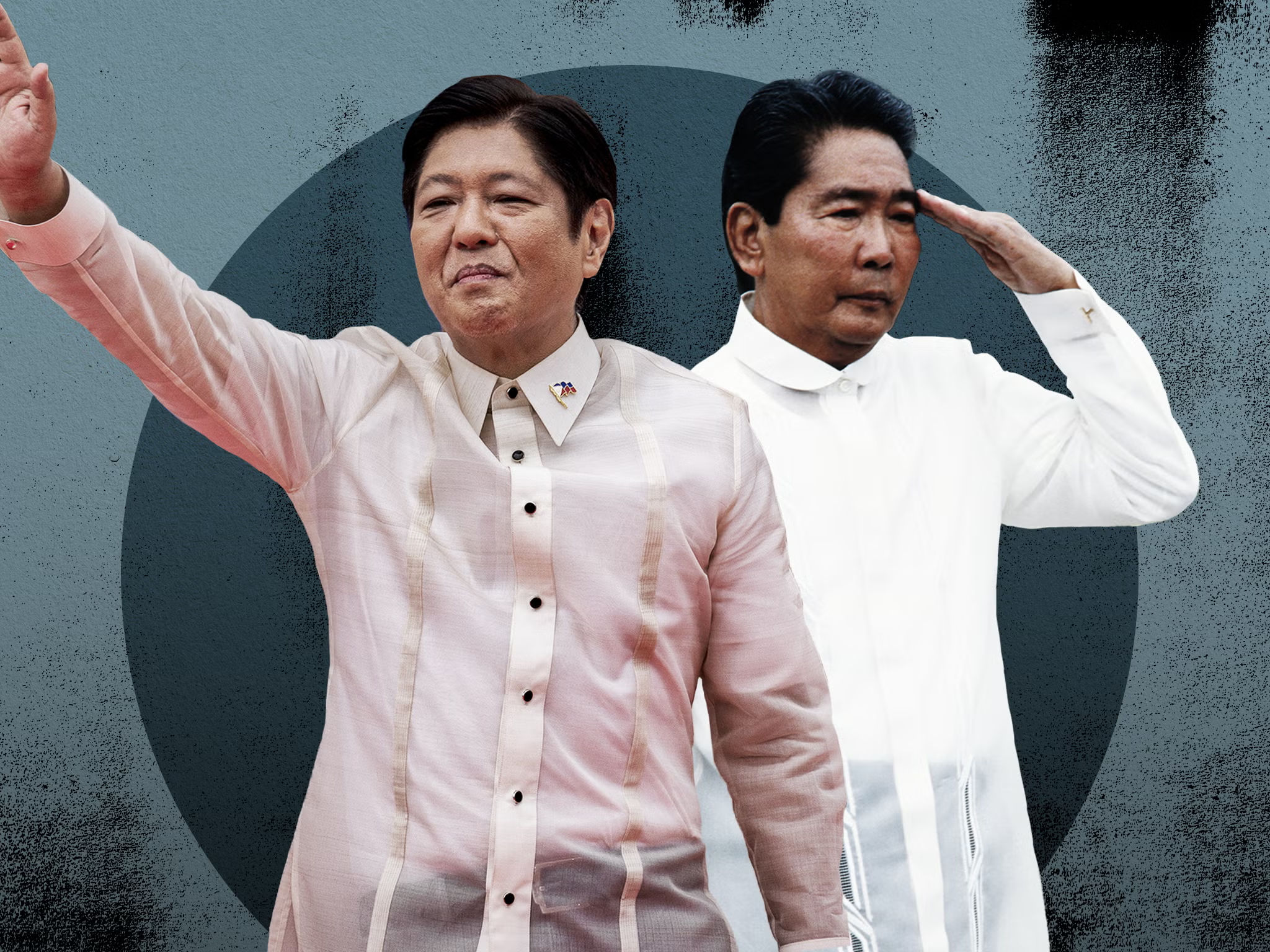

It took another 14 years and another “first quarter storm”—the tumultuous months of January and February 1986, following the snap election—to depose Marcos. Fifteen years later in 2001, on another January, yet another president, Joseph Estrada, would be hounded out of office over issues of corruption.

What is it about these first quarters that provoke such firestorms? And do we still have it in us to begin the year on a note of political resolve?

I’ve been worried, like many of us, that the Christmas break, the congressional recess, and intervening issues may have sucked the steam out of the public outrage that boiled over the flood-control scam last year, and lulled the government into thinking that the worst was over and that we could all just settle back into the old routine: let the Ombudsman and the courts do their job, etc.

What’s worse is if we fall into that mindset, too. The budget deliberations, the Cabral death mystery, the Leviste files, the Barzaga antics, and even a traffic violation episode have all seemed to be distractions from our laser-sharp focus on bringing the crooks to justice. But in fact, they’re all of one piece: demanding better and honest government, the overarching issue we need to press.

And just as the radicals seized the initiative from the moderates 56 years ago, FM’s son, PBBM, can still seize the day by going against all expectations, even against his own nature, and finishing what he may have inadvertently begun: weeding out corruption in government. Never mind the motive—reviving his sagging poll numbers, saving his skin, redeeming the Marcos name, or leaving a worthy legacy behind. He has little choice, if he and his family are to survive.

There are immediate and concrete steps he can take to achieve this:

1. Activate the Independent People’s Commission. The people are waiting for his next move in this respect; get the enabling law passed and the job done.

2. Impeach VP Sara Duterte. The grounds haven’t changed, and the urgency can only increase as 2028 approaches.

3. Revamp the Cabinet, but replace the non-performers. PBBM knows who they are as well as the public—especially the publicity-seekers whose departments haven’t delivered.

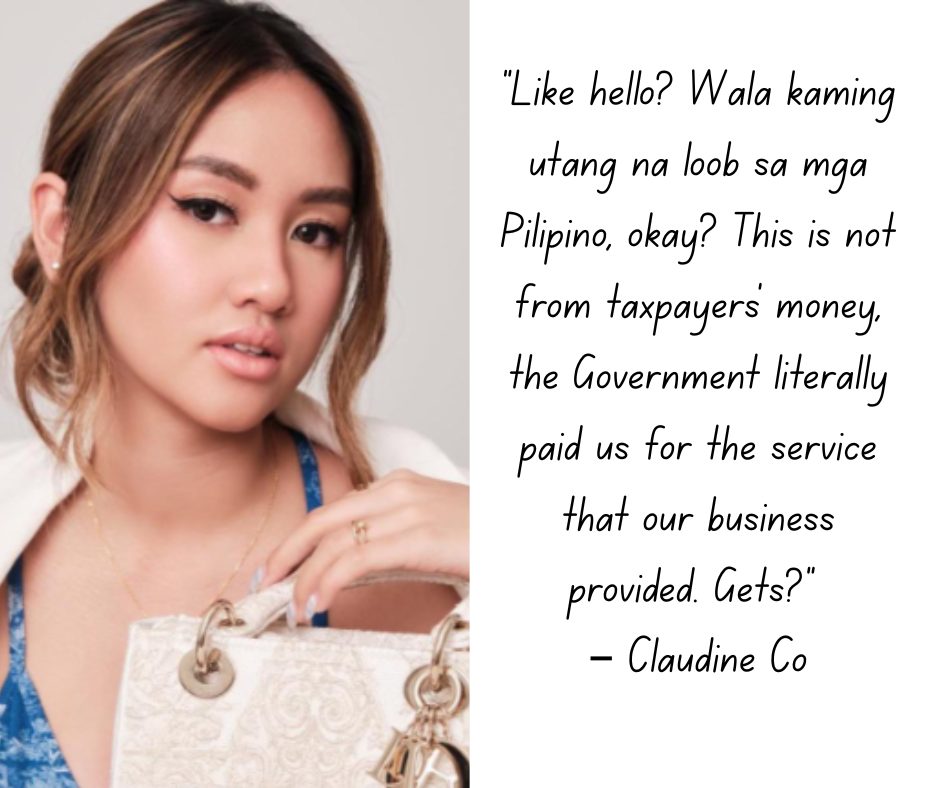

4. Find Atong Ang, Zaldy Co, Harry Roque, etc. and jail the big fish—including political allies. It’s hard to believe that with billions in intelligence funds, the administration can’t track and nail these highly visible fugitives down. Justice is perception.

Do these, and maybe we’ll avoid the generational kind of flare-up and meltdown that followed January 26, 1970.