Qwertyman for Monday, April 29, 2024

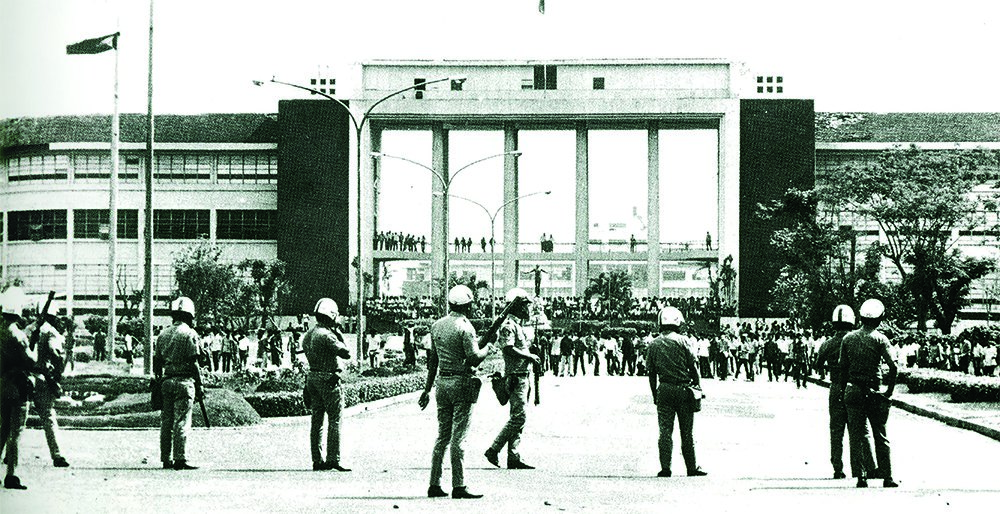

A WAVE of pro-Palestinian protests has been sweeping American college campuses, prompting academic administrators and political leaders to push back and invoke their powers—including calling in the police—to curtail the demonstrations.

House Speaker Mike Johnson—a Trump ally and staunch supporter of Israel—probably spoke for his ilk when he told protesting students at Columbia to “Go back to class! Stop wasting your parents’ money!” He also called on Columbia University president Minouche Shafik—an Oxford Economics PhD and English baroness who also happens to have been born in Alexandria, Egypt to Muslim parents—to resign for not moving strongly enough against antisemitism on the Columbia campus, despite Shafik’s controversial suspension of pro-Palestine student groups earlier and her resort to police action, resulting in mass arrests.

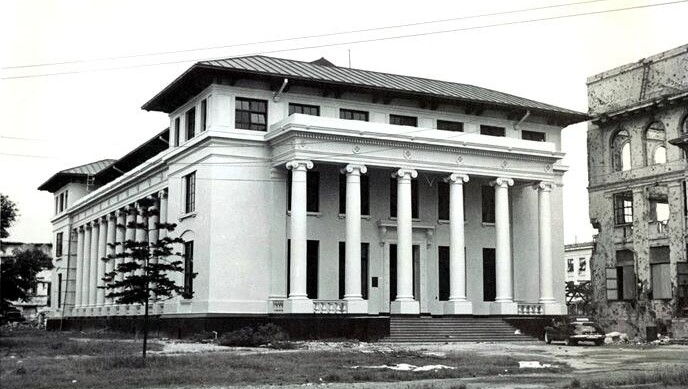

The protests and the violent response to them threw me back to 1968, when the world’s streets from Chicago to Paris shook from the boots of students and workers marching against the Vietnam War, for civil rights, and for women’s liberation. In the Philippines, student organizations such as the SCAUP and the newly formed SDK took up the same causes, on top of a resurgent nationalism. I was too young to have been part of these great movements then, although we marched in high school for “student power,” whatever that meant. I would get deeply involved as the decade turned, infected by the inescapable ferment in the air; in 1973 I would realize that protest had a price when I spent seven months in martial-law prison.

I’ve tried hard to think what it would be like to be 18 and a student today, what cause would drive me to the streets and to pitch a tent on the campus grass. While we Pinoys have our sympathies, Gaza seems too distant for us to mobilize for, and certainly we don’t lack for domestic issues to be bothered by, although our level of tolerance appears to have risen over time. In 1971, a 10-centavo increase in oil prices was enough for us to trigger the Diliman Commune; today we routinely wait for Tuesday’s inevitable announcement of gas price hikes and sigh.

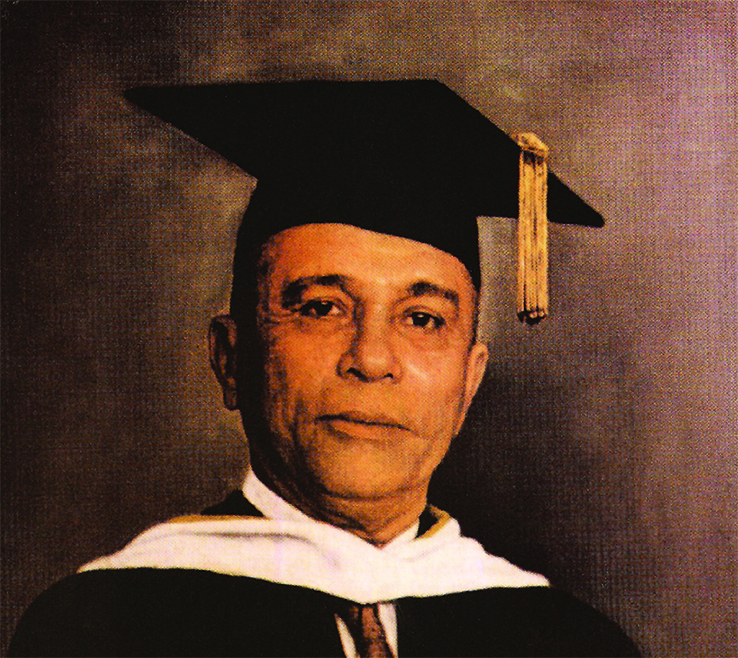

Perhaps time and age do bring about shifts in perspective; some leftist firebrands of my youth have now become darlings of the right, and I myself have moved much closer to the center, ironically morphing from student activist to university official at the time of my retirement.

As that administrator—at a university where protesting is practically part of the curriculum—I can appreciate the bind Dr. Shafik now finds herself in, hemmed in from both left and right, with the complexity of her thinking and the brilliance of her own achievements reduced to a single issue: how to deal with students who won’t “go back to class and stop wasting their parents’ money,” as Speaker Johnson would have it, and will instead insist on their right to self-expression, whatever the cost. Aggressiveness, audacity, and even insolence will come with the territory. Persons in authority become natural targets of one’s rejection of things as they are; the preceding two generations are to be held immediately responsible for things gone wrong.

I recalled a time when UP students barged into Quezon Hall to interrupt a meeting of the Board of Regents to plead their cause. Some furniture was scuffed, but the president sat down with the students and discussed their demands. No one left happy, of course, but what had to be said on both sides was said. At another meeting later, someone asked if the students involved should have been sanctioned for what they did. I had to butt in to pour cold water on that notion, knowing that any punitive action would just worsen the problem. Open doors, I said, don’t shut them; this is UP—that kind of protest is what makes us UP, and our kind of engaged response is also what makes us UP.

Some will say that these outbursts are but cyclical, and that young people never learn, in repeating what their now-jaded seniors did way back when. But then the State never learns either, by responding to student protests today the way they did back in 1968, with shields and truncheons, effectively affirming everything the young suspect about elderly authority.

The Israel-Hamas war—now magnified, through many lenses, into an Israeli war on Palestinians—is a particularly thorny issue for American academia and for a public habituated to looking at the Jewish people as biblical heroes and historical victims. Gaza has turned that perception around for many, with the aggrieved now seen as the aggressors. In my column two weeks ago, I agreed with that re-evaluation, although I was careful to take the middle road and to condemn the excesses—committed for whatever reason—on both sides.

Not surprisingly, I quickly got blowback from both my pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian friends. War is always ugly, one said, and Israel has to do what it must to save itself; the Hamas attack on October 7 was overblown by propaganda, said another, and it was something that Israel had coming.

I still accept neither extreme; call me naïve and even Pollyannish, but I stand not with Israel nor with Palestine, but for peace and justice, which are not exclusive to one side, and can only be achieved by both working and living together. You can argue all the politics and the history you want, but there is absolutely no humane rationalization for the rape of women, the murder of children, and yes, even the killing of innocent men—not even the prospect of potentially saving more lives, the very argument behind the incineration of 200,000 Japanese in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, an act of war we all benefited from, but cannot call guiltless.

In a conflict as brutal and as polarizing as this one, “middle” never quite cuts it, and the excess of one will always be justified by the excess of the other. (To complicate my ambivalence, some issues do seem to have no middle, like Ukraine.) There have been no mass protests or demonstrations to advance my kind of moderation, and I don’t expect students, whether in Columbia or UP, to take to the streets flashing “peace” signs.

And in mentioning that, I think I’ve put a finger on one difference between 1968 and 2024: “peaceniks” were neither pro-Saigon nor pro-Hanoi, although her critics were quick to paint Jane Fonda red; they just wanted America out of a war that was none of its business. There was an innocence to that that seems to have been lost in our hyper-informed and over-analyzed century. We feel compelled to choose with passion and precision, and are defined by our choices, from politics to sneakers.