Qwertyman for Monday, September 11, 2023

AT ABOUT this time fifty years ago, I was newly released from martial-law prison after seven months of what everyone euphemistically called “detention,” and wondering what to do with the rest of my life. I was just nineteen, so I suppose you could say that I had a lot of living ahead of me, but I felt very differently then. More than a dozen of my friends—all of them in their twenties or even younger—had died horrible deaths fighting the regime. We exalted them as the martyrs that they were, but grimly realized and acknowledged that given how things were going, we ourselves would be fortunate to see the ripe old age of thirty.

I had been arrested at home on a cold January morning in 1973, just past midnight. Like many student activists, I had dropped out of college during the First Quarter Storm of the early 1970s. But instead of joining “the movement” full-time, I improbably found a job with a newspaper as a general-assignments reporter. It was heady stuff at age eighteen, covering three-alarm fires, floodwater rescues, and the very same demonstrations I had joined on the other side of the police barricades. And then martial law was declared—I was actually covering a rally in UP, and thought I had a scoop when a radio station nearby came under fire from the Metrocom, only to be told by my night editor when I tried to phone the story in that we no longer had a newspaper to publish, because soldiers had taken over the office.

Over the next few months I shuttled between part-time jobs and clandestine meetings with the anti-martial law underground, moving around the city. I wasn’t doing much, given how green I was, but I thought it was important to take part in the resistance in whatever way. And then when Christmas came, like a good boy, I went home to my parents and foolishly had a chat with a neighbor who turned out to be a military asset. Not long after, a posse of soldiers appeared at our door, and when my father nudged me awake, I had a gun pointed at my face. I was being arrested under a catch-all “Arrest, Search, and Seizure Order” or ASSO issued by the Defense Minister, Juan Ponce Enrile, for whom I would ironically be writing some speeches during his post-EDSA reincarnation (he won’t remember that, as I was a tiny mouse in the office).

My release in August 1973 came right out of a Kafka story. I was taking a shower one morning in our prison—which, by the way, is roughly where St. Luke’s BGC is today—when I heard my name being called over the PA system. “Dalisay, report to the guardhouse immediately!” The last time I had done that, after one Sunday dinner, I had been beaten up by some drunken guards just for the heck of it, so I groaned when I heard the announcement. Not again, and so early? As it happened, I was received by an Army officer with a stack of papers. He pulled mine out, squinted at it, and said, “Dalisay, you’re still here? Pack your things. We have nothing on you.” The first place I visited after I went home was the AS Steps in UP, where we had gathered for many a raucous rally; it was vacant and deathly silent, and I knew that I wasn’t going back to school just then. Only after a long detour—working as a printmaker, a writer, an economist, and meeting Beng and fathering Demi—did I return to UP and graduate with my degree at age thirty.

I’ve written about my activism and incarceration in my first novel, Killing Time in a Warm Place (Anvil Publishing, 1992), and it isn’t what this column is really about. Rather, it’s about the aftermath, about having a life after martial law, and an unexpectedly long one at that.

For any activist from my generation who’s still alive, every breath we’ve taken after our 30th birthday is a grace note—what the dictionary describes as “an extra note added as an embellishment and not essential to the harmony or melody”—in other words, a bonus. Considering that we could have been gunned down like dogs or buried alive like some of our comrades were, you can understand why we feel that way. It’s almost absurd to contemplate, but education, marriage, career, success, fame, fortune—and all the downsides and flipsides that come with them—all these were a long string of surprises, any one of which might never have happened, but for a twist of fate or a stroke of luck (clichés, like life’s very milestones, but ones we appreciate).

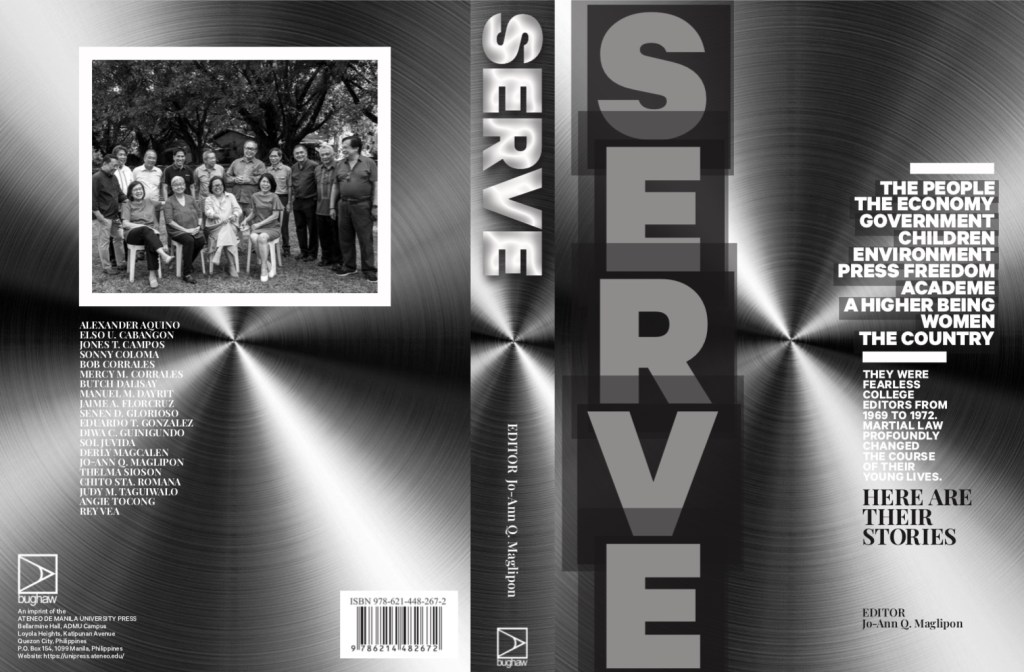

When my fellow FQSers and I—all college editors who were part of the SERVE book that I wrote about last week and that we launched last Saturday—gathered around a table before the launch to pre-sign some copies, we noted with much chuckling how surprisingly old we had become. We were beset by diabetes and hypertension, which were lethal enough but easier to bear than the four bullets one of us took to his face and body; he was with us that day, laughing, his spirits buoyed by his fervent Christian faith.

We had become university presidents and professors, Cabinet secretaries, CEOs, magazine editors, pastors, and opinion-makers. I don’t think there was anyone in that room who believed any longer in the necessity nor the efficacy of violence, but neither did anyone imagine that our youthful goals had been met, that the country had become a kinder place, and that our work for justice and freedom was done. We had come to terms with our past, were busily in the present, and were hoping to enjoy what little we had left of our extended lives. But like those shaken passengers who stagger away from a crashed plane, leaving the uncounted dead behind, I’m sure that we felt driven by survivor’s guilt to make the most meaning of our gifted years, to do well and to do good, and to serve our people in any way we could.

We learned that everything may be political, but also that politics is not everything, and that the road to happiness and deliverance may be wider than we had thought. I myself have resolved that even as I fight on for truth and beauty, I will not allow my happiness to be determined by our political vicissitudes, if I can help it. That will be my sweet revenge on my jailers. I will survive you, live a fuller life, and meet my Maker with a clear conscience and a smile.