Penman for Monday, May 25, 2015

Penman for Monday, May 25, 2015

I FLEW out to Toronto in Canada a little over a week ago to take part in that city’s Festival of Literary Arts, possibly the first Filipino author to join that long-running festival, now on its 15th year. Previously, the festival had focused on South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka), but has recently opened itself up to more representation from East Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, thus my inclusion in this year’s roster of invited writers and speakers.

Over a weekend, from Friday to Sunday (May 15-17), several dozen representatives from these regions and from Canada met in various venues on the scenic campus of the University of Toronto and its environs to tackle issues and problems besetting writers and publishers from outside the global centers. How does a writer from the periphery break through to the center? Or is that “periphery” its own legitimate center? Is yearning for publication and validation in the West a vestige of the colonial mindset, an experience shared by all the countries represented in Toronto?

Aside from these seminal discussions, of course, the meeting was first and foremost a festival, a sharing of the artists’ finest work, and I felt privileged to be introduced to authors and creations I would otherwise have totally missed or blithely ignored. With many of the authors coming from expatriate and postcolonial backgrounds, the offerings were rich and deeply nuanced, the talents outstanding.

Among others, I discovered a major international writer in the festival director, the novelist M. G. Vassanji, who had been born in Tanzania in East Africa, and whose account of his pilgrimage to his ancestral roots across the ocean (A Place Within: Rediscovering India) is a modern classic of creative nonfiction—a sympathetic but unsentimental and often searingly critical chronicle of his encounter with the sprawling reality of India today.

The visit also allowed me to reconnect with some old Filipino friends who had migrated to Toronto and had built new lives there. I was very graciously taken out to a scrumptious dimsum lunch in Toronto’s fabled Chinatown by Patty Rivera and her husband Joe. Patty and I worked together 40 years ago as writers and editors at the National Economic and Development Authority (an unlikely Camelot for young writers and artists under the patronage and protection of then-Sec. Gerry Sicat).

Though trained and still active as an editor and journalist, Patty has since developed into an accomplished and prizewinning poet, with three volumes to her name. Her first collection, Puti/White, was shortlisted for the 2006 Trillium Book Award for Poetry. Patty’s husband Joe, a former Ford executive who also wrote plays in the Philippines, became a lawyer in Canada and then, upon his recent retirement, turned to painting, an avocation in which he demonstrates a most unlawyerly exuberance. I also met and was happy to engage with some Alpha Sigma fraternity brothers led by Amiel “Bavie” de la Cruz, who now runs his own accounting firm in Toronto.  Patty and Joe arranged a reading for me with a large and lively group of Toronto-based Pinoys (including Hermie and Mila Garcia, the moving spirits behind Canada’s longest-running Filipino newspaper, the Philippine Reporter, and expat poet Naya Valdellon); this was held in the very stylish apartment of writer-artist Socky Pitargue, and a great time was had by all as we threshed out the travails of Philippine literature and politics, two deathless topics that occupy me on every one of these overseas sorties.

Patty and Joe arranged a reading for me with a large and lively group of Toronto-based Pinoys (including Hermie and Mila Garcia, the moving spirits behind Canada’s longest-running Filipino newspaper, the Philippine Reporter, and expat poet Naya Valdellon); this was held in the very stylish apartment of writer-artist Socky Pitargue, and a great time was had by all as we threshed out the travails of Philippine literature and politics, two deathless topics that occupy me on every one of these overseas sorties.  Yet another meaningful encounter I had, thanks to the festival organizers, was with two classes of high school students at the Mother Teresa Catholic School in Scarborough, a Toronto suburb with a high concentration of Asian students, including Filipinos. These teenagers had very likely never met a living writer before, let alone a Filipino one, and I was glad to try and show them that we do exist, and that we have something to say. I, too, learned something from their teacher Kathy Katarzyna, who ended our session with a terrific quote from the Canadian poet Leonard Cohen: “There’s a crack in everything…. That’s how the light gets in.”

Yet another meaningful encounter I had, thanks to the festival organizers, was with two classes of high school students at the Mother Teresa Catholic School in Scarborough, a Toronto suburb with a high concentration of Asian students, including Filipinos. These teenagers had very likely never met a living writer before, let alone a Filipino one, and I was glad to try and show them that we do exist, and that we have something to say. I, too, learned something from their teacher Kathy Katarzyna, who ended our session with a terrific quote from the Canadian poet Leonard Cohen: “There’s a crack in everything…. That’s how the light gets in.”

Many thanks to the Sri Lankan poet Aparna Halpe for taking me to the school. Of course, my thanks wouldn’t be complete without acknowledging the help and support of my sister Elaine Sudeikis and her husband Eddie, who flew in from Washington, DC to join me at the festival and to show me Toronto and a bit of Ontario (most notably Niagara Falls—we walked over to the US side as well for my shortest visit to the US, ever). Ed’s dad Al—all of 92 but still feisty—also gave me a little taste of Lithuania in Toronto.

And the visit would never have happened for me without the recommendation of Prof. Chelva Kanagayakam, an eminent scholar and festival founder whom I’d met in Manila, who tragically died of a heart attack a few months before the festival, on the very day he was inducted into the Royal Society of Canada. I found Toronto itself to be a highly livable and largely safe city (guns are under strict control in Canada), with a vibrant ethnic mix.

One out of every two Torontonians comes from somewhere else, and Vietnamese, Tibetan, and Puerto Rican restaurants stand cheek-by-jowl beside each other, not to mention a Chinatown noted to be among North America’s best culinary havens. (A Pinoy food store aptly named “Butchokoy” stood a block away from my lovely B&B—a three-storey house from 1853—on Dunn Street.) Victorian structures still in use by the university and the city government contrast sharply with ultramodern architecture in an eclectically energetic skyline. Seekers of the funky and the quirky can have their fill in the city’s counterculture-inspired Kensington Market.  For someone schooled in Americana, this exposure to things Canadian was an interesting re-education—to think, for example, in terms of “Tim Hortons” instead of Starbucks or Seattle’s Best; of “Roots” instead of Gap; of “Hudson Bay” instead of Sears or JC Penney, etc.

For someone schooled in Americana, this exposure to things Canadian was an interesting re-education—to think, for example, in terms of “Tim Hortons” instead of Starbucks or Seattle’s Best; of “Roots” instead of Gap; of “Hudson Bay” instead of Sears or JC Penney, etc.

But the most useful re-orientation took place for me at the festival itself, in reminding me that we have a lot to learn from South Asia as far as developing readerships in local languages is concerned, among other issues. We Filipinos think we’re well traveled and globally savvy, but we actually don’t get around enough in terms of mixing with our fellow Asians, let alone Africans. We seek out Western—specifically American—tutelage and patronage, often to our own deep disappointment.

It seems ironic that I had to learn this in Toronto—a true cosmopolis like New York—but sometimes you have to stand in the West for a better view eastward.

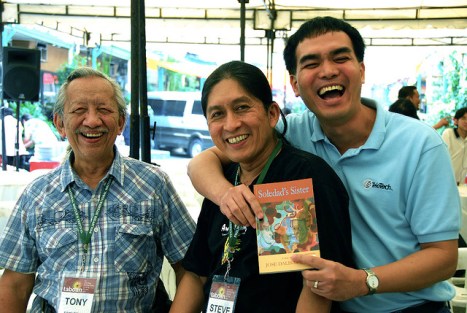

[Group photo from philippinereporter.com]

Penman for Monday, November 4, 2013

Penman for Monday, November 4, 2013