Qwertyman for Monday, December 30, 2024

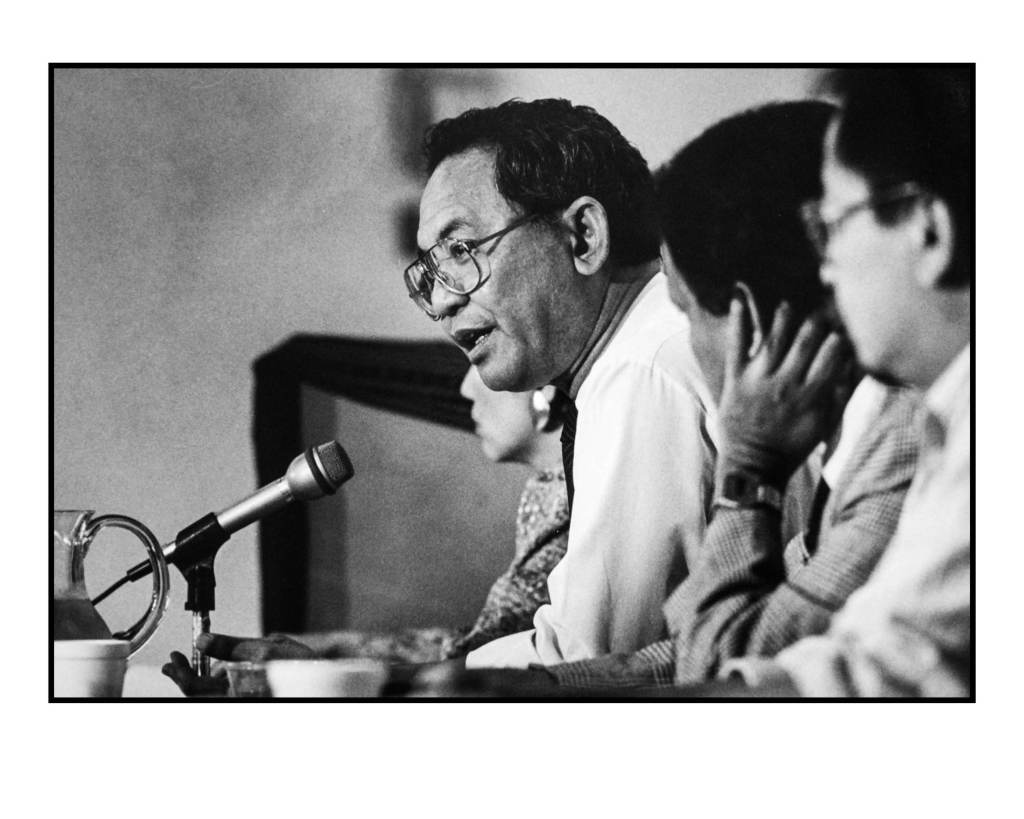

THIS WEEK I continue with excerpts from my interview with the late Francisco “Dodong” Nemenzo, on his recollections of his genesis as a young intellectual and activist at the University of the Philippines in the 1950s.

“It was all a popularity contest. Everything just seemed to be socials. Homobono ‘Bon’ Adaza, who was then the editor of the Philippine Collegian, tried to organize a socialist club with me. Bon even put out an announcement for a meeting. Bon and I were contemporaries, but he was a year older than me. I think I was a senior by then. I was living with my father on campus, since he was a professor here. We had a cottage in Area 2, then we later moved to Area 14. Our whole family was here.

“It was because of my readings. I had already read the history of the socialist movement, and I was fascinated by that so we formed a socialist club. I think just three of us turned up for the meeting—the third was Princess. After that we were always together. We weren’t going steady yet then. We continued being friends because she was the only one who listened to my sermons on socialism. You ask her, but I don’t think she had any association with socialism before. We had just that one meeting.

“Bon was eventually expelled from UP, but I had a hand in his election as chairman of the Student Council and editor of the Collegian twice because we were friends. The editor was elected from among the topnotchers of the exam.

“The UPSCAns didn’t have a candidate who passed the exam, who were all frat boys. Bon landed in the top three, but he had no supporters. I bargained with the UPSCAns because they held the majority. So I used my vote in the council to push for Bon. Eventually he became editor of the Collegian.

“Together with the chairman of the council and also the leader of the UPSCA, we decided to hold the first student strike. This was because for one and a half years, UP had no president, with Enrique Virata serving as acting president. It came down to a stalemate between Vicente Sinco and Gonzalo Gonzalez. Squabbling behind them were Jose P. Laurel, who represented the Senate on the Board of Regents, and Carlos P. Garcia who was supporting Gonzalez. No one could get the majority. I was on that strike. I proposed a solution arguing for the Board to take decisive action but also endorsing Salvador Lopez, whose essays I loved, for president. The UPSCANs didn’t care who won, as long as we had a president.

“Our strike paralyzed the campus for a couple of days. It didn’t last as long as the Diliman Commune, but it was the first—and it was my first mass action. I was the one who was planning the tactics.

“I was really looking for allies when I met this labor leader who used to be the secretary-general of the Federation of Free Farmers. [We’ll call him Hernando for this account, pending verification of the name—JD.]He claimed to be a socialist and he seemed to have read books on socialism. He was a layman. He was the one who introduced me to labor leaders such as Ignacio Lacsina and Blas Ople. They had a group of young people who revolved around Lacsina, and they met at his office in Escolta.

“But I continued my reading. Sometimes I felt alienated because they weren’t Marxists. They were just for nationalization, and I felt more advanced than they were. There were other students there, but they were not as involved as I was. When the Suez Crisis exploded in 1957, the Americans intervened in Lebanon. We decided to picket the US embassy. We were already using the word ‘imperialism’ then. Prominent labor leaders were there, including Hernando. When we got there, the labor attaché invited us inside to have breakfast with the US ambassador. I didn’t want to go in, but Ople and Lacsina thought they could change US policy by convincing the ambassador, so we did. I was utterly disgusted by that experience.

“I was due then to go to US for my PhD, on a Rockefeller fellowship at Columbia University. Our demonstration took place just a few months before I was to leave. I was an instructor in UP and my college wanted me take up Public Ad, but I wanted to get out of that so I chose Political Sociology. I had become an admirer of C. Wright Mills who worked there and I wanted to work with him, only to find out that he didn’t want to handle graduate courses.

“I already had a room at the International House in Columbia. Everything was prepared. I already had my visa. But on the day I was supposed to leave, the embassy told me that I could not leave. The consul general showed me the immigration law, which banned the entry of communists, anarchists, drug addicts, and prostitutes.

“I think they had some earlier information about me because Lacsina later told me that Hernando was a CIA agent. He said that once, he and Blas Ople wanted to invite Hernando for a drink so they could get him drunk and then ply him with questions to extract the truth. What happened instead was that Blas got drunk first so nothing happened. Then he lashed out at Hernando and told him to his face that he was a CIA agent, and cursed him for blocking me from taking up my scholarship in the US. Looking back, I think Lacsina was right!”

Dodong Nemenzo eventually went to the University of Manchester in the UK for his PhD in Political History. He returned to serve as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, chancellor of UP Visayas, faculty regent, and 18th president of the University of the Philippines. He married Ana Maria “Princess” Ronquillo and they had three children—one of whom, the mathematician Fidel, became chancellor of UP Diliman.