Penman for Monday, January 23, 2017

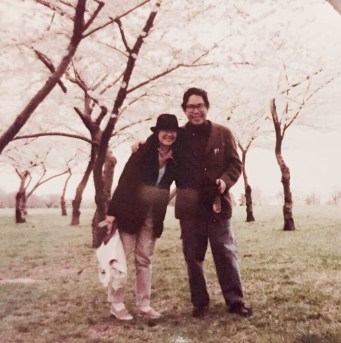

A COUPLE of weekends ago, against all odds, Beng and I celebrated our 43rd wedding anniversary and not coincidentally my 63rd birthday. It seemed like an inspired idea at the time to get hitched as I turned 20, but over the years I’ve wondered if I should have given each day its proper due, and doubled my presents that way. But I soon realized that I was never going to get or find a better gift than Beng—patient, forgiving, and gentle Beng—so January 15 has largely been a day for two.

Around Christmas I start thinking about how and where best we can spend the day, and this year, with UP having shifted its academic calendar to begin the school term in mid-January, we could have opted, funds permitting, to fly out to some exotic destination like Penang or Pattaya (or, heck, why not Paris?).

Instead, after some Googling, we ended up in the most unlikely of romantic locales—Pasay City, at the Henry Hotel along F.B. Harrison, to be more specific, where the magic begins once the gate opens.

I’d read about the Henry somewhere before and had seen pictures of the place—a visual and sentimental journey back to the 1950s, with its stately main house and sculpted gardens, and I remember being amazed even then by the fact that such a sylvan hideaway could exist in the heart (or less kindly the armpit) of the metropolis. It was high time we checked in for a weekend staycation; the saved airfare alone would answer for the room. And being staunch northerners, we barely knew the southern sector of the city, except for visits to the Cultural Center and the Luneta area. We hadn’t even reconnoitered the cavernous Mall of Asia except again for the briefest sorties.

But again that’s not entirely true, because I had actually grown up in Pasay in the late ’50s and early ’60s, in a house on P. Manahan branching off F.B. Harrison. It was a neighborhood interlaced with catwalks, off one of which I once fell into the fetid water while showing off my brand-new cowboy outfit, which I had probably received for my fifth or sixth birthday.

That bit of unpleasantness aside, I could still remember afternoons swimming in Manila Bay and lounging on the long beach chairs by the sea wall, riding the double-decker Matorco buses up and down what was still Dewey Boulevard, and munching on foot-long hotdogs at the Brown Derby.

So this weekend in Pasay was something of a homecoming for me, even if all the old landmarks were gone. What’s now the Henry was already there when I was humming the Tom Dooley song, but it wasn’t a hotel yet then but a sprawling compound of large squarish but stylish wooden houses flanking a white concrete main house, amid greenery tamed and teased by Ildefonso P. Santos, who would go on to become a National Artist for Architecture.

The 32-room Henry was built by its new owners out of that layout, preserving as much of the old while providing such modern amenities as wi-fi and air-conditioning. A long gravel driveway leads to a fountain and a roundabout fronting the main house, past a curtain of angel’s-hair vines; a swimming pool glows opalescent blue amid the verdure; the main house stands proud but welcoming.

I’ll report that we had a most pleasant and restful stay, helped along by an unobtrusively efficient staff. We luxuriated in the fluffy pillows and the hot shower. It was a bonus to discover that the art gallery of an acquaintance, Albert Avellana, occupied one of the houses in the compound.

But our anniversary weekend wasn’t meant to be spent cooped up in a room, however charming the ambience. We’ve lately been used to taking 5-7 kilometer walks as part of our seniors’ exercise regimen, so we gamely walked for our bangus and salad breakfast to a restaurant near MOA, and walked many kilometers more within the mall itself.

Staying at the chic Henry was in a way the compleat anti-mall experience, but Beng and I have never pretended to be anything but pedestrian, so that for us was the exotic treat. The mall, like all markets, was familiar territory.

We took in a couple of action movies, buying more popcorn than we could ingest, and oohed at all the nice clothes that wouldn’t fit us. When we had lunch of ukoy and suam na halaya at the KKK restaurant, Beng loudly let the manager know that we were celebrating our 43rd, snagging us a free dessert of leche flan. Hankering for a sushi dinner, we misread Chinese for Japanese and stumbled into Masuki, which served huge bowls of my all-time favorite, Ma Mon Luk-style mami.

The literal highlight of our weekend had taken place earlier that afternoon. We had asked ourselves, the night before, “What kind of cheap, mindless fun haven’t we tried in a long time?” (Not that, naughty boys and girls.) We paid P150 each the next day for the answer: an eight-minute joyride up and down the MOA Eye, the big white Ferris wheel from whose apex we took selfies before tumbling out of our pod, giggling, to rejoin teeming humanity and the surefooted ordinariness of things.

Penman for Monday, August 8, 2016

Penman for Monday, August 8, 2016

Penman for Monday, August 1, 2016

Penman for Monday, August 1, 2016