Penman for Sunday, August 11, 2024

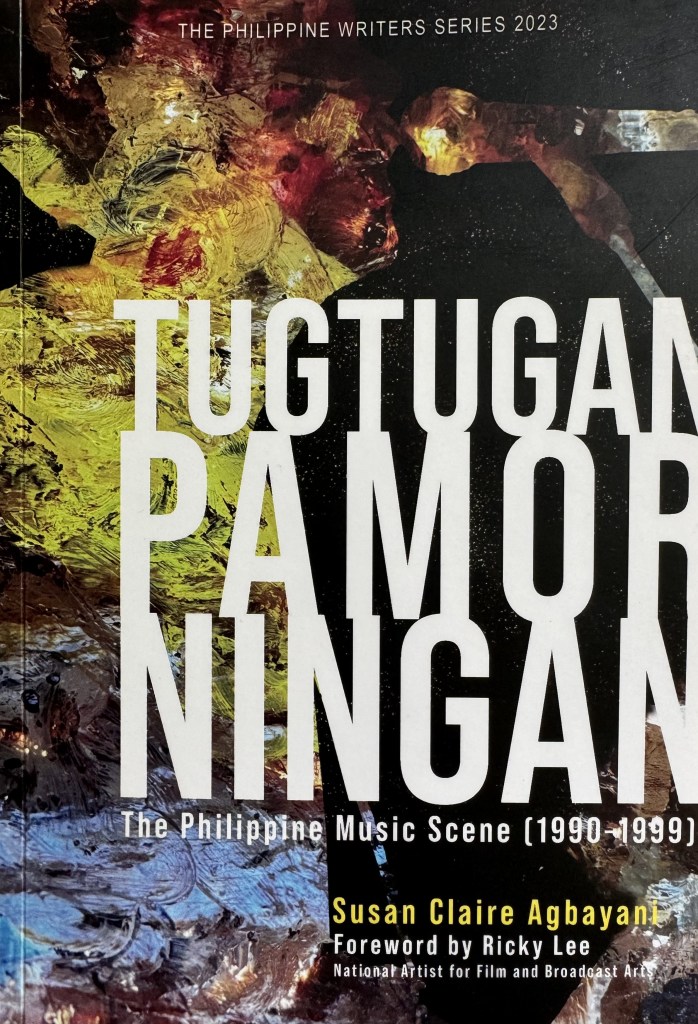

AMONG THIS year’s most interesting new books is one that’s neither a novel nor a political exposé, but a musical chronicle of a decade that many Filipinos now look back on with a certain nostalgia, albeit for different reasons—the 1990s.

Say “the Nineties,” and a range of responses will come to mind depending on how old you were then. For today’s seniors, the core of it was likely FVR’s infectious optimism over “Philippines 2000,” the relative stability we had gained after the anti-Cory coups and in anticipation of our centennial in 1998. For those younger but old enough to drink beer, it was the age of the Eraserheads, Clubb Dredd, the ‘70s Bistro, and Mayric’s, an explosion of OPM like we had seen back in the 1970s but with a harder and sharper edge.

It’s that latter scenario—set against the context of our transition from Cory to FVR to Erap—that’s captured in Susan Claire Agbayani’s landmark Tugtugan Pamorningan: The Philippine Music Scene 1990-1999 (University of the Philippines Press, 2024, part of the Philippine Writers Series of the UP Institute of Creative Writing). An indefatigable cultural journalist, publicist, and sometime concert producer (and also, I must proudly admit, my former student), Claire was among the very few writers who could have undertaken this job (Eric Caruncho, Jessica Zafra, and Pocholo Concepcion, all of whom she cites, would have been the others).

Comprehensively, the book’s chapters cover bars and concerts, the music scene, personality profiles, duos and trios, pop/jazz/R&B/show bands, alternative/rock bands, the Eraserheads (yes, a chapter all to their own), Mr. and Mss. Saigon, and visiting acts, rounded out by a gallery of period pics.

As a compilation of pieces from Claire’s reportage at that time, the book revives not only the music but also the issues besetting the industry then, such as Sen. Tito Sotto’s wanting to ban the Eraserheads song “Alapaap” for supposedly promoting drug abuse. Priceless vignettes abound, such as that of Basil Valdez singing “Ama Namin” to composer George Canseco’s wife over the phone, three days before she died, and of Ely Buendia telling Nonoy Zuñiga that he had won a singing competition in school with the latter’s “Doon Lang.” We learn about Humanities teacher and all-around performer Edru Abraham’s Lebanese ancestry and how it connects him to world music.

The best scenes, I think, are the saddest ones, such as this piece on a jazz diva:

“She goes around greeting the waiters, then the manager. At last, she sits on a stool, and croons ‘Left Alone,’ the song after which the bar was named. She closes her eyes, closed them more tightly as a couple walks out in the middle of her song. The waiters laugh loudly in the background, occupied with their own concerns. Those who remain inside the bar talk not in whispers. No, they don’t know her. They don’t know Annie Brazil.”

But ultimately it’s the music, the sheer variety and vitality of it, that surges through, so innate to the Filipino and so necessary. If there were an Olympics for music, we’d make the podium in all the categories, and Tugtugan Pamorningan reminds us why. As the title implies, it’s a nightlong festival for us when the music starts. But like night itself, even the Nineties came to an end, with the 2000s bringing in MP3, iTunes, and Spotify, and somehow the smoky, small-bar intimacy that the previous decade connoted gave way to Taylor Swift mega-concerts that people actually flew out to instead of taking a taxi.

I contributed an afterword to the book, so here’s a bit more of what I had to say:

I was a bit too old by the time the ‘90s came along to experience it in the way Claire has so capably and faithfully chronicled in this book, but still young enough to imbibe its energy and its excesses. I was 36 in 1990, finishing my PhD in the States, and when I returned to Manila the following year after five years of being away, I found a radically different scene from the one I’d left just after EDSA. I had a lot to adjust to, and somehow San Miguel beer and the city’s new nightlife seemed to ease those pains, at least until the next morning.

That was how, despite being too old to know the Eraserheads and their music, I managed to stumble once or twice into Club Dredd, Mayrics, the ‘70s Bistro, and a few other meccas mentioned here, but mostly just out of curiosity. I guess I was looking for something else, and found it on Timog Avenue with my partners-in-crime Charlson Ong and Arnold Azurin, finishing up with some coffee or a beer for the road at Sam’s Diner on Quezon Avenue at 3 am. I wasn’t even a Penguin person—I never thought of myself as being hip or cool—and I preferred hanging out with journos after work in that kebab place on Timog.

That was my life as a barfly—which was also how my newspaper column got that title—and its soundtrack consisted of Basia, Bryan Adams, and “Total Eclipse of the Heart.” I wasn’t much into bands—no one could beat the Beatles—and OPM for me meant APO and Louie Ocampo, whose songs were singable and could make me smile, which I needed a lot. It was a wild time, when I was smoking and drinking and messing around town in my white VW, courting disaster, until one day I found my way home and decided to stay there forever.

That makes the ‘90s sound like some kind of inferno, but now that I think about it, it was the last gasp of innocence before the 2000s and everything we associate with it—9/11, GMA and Erap, the Internet, the iPod, social media, K-pop, tokhang, Trump, the pandemic, the Marcos restoration, and AI—came in. There was a simple-mindedness even to our vices then; truth was truth, fake was fake, and it was easy to tell one from the other. It was rough and raw in many ways—even our 14.4K modems screeched like cats in heat when they connected—but we still got wide-eyed about the possibility of extra-terrestial menace in The X-Files, and we may even have believed that FVR’s “Philippines 2000” was going to be a better place even as we got worried sick over what Y2K would bring, so there remained a tender spot of credulity in us.

That’s all gone now, like Jacqui Magno’s voice, replaced by CGIs, deep fakes, and other synthetics produced by FaceMagic and ChatGPT.

I can’t honestly say that I miss the ‘90s, and I feel much relieved to have survived them, but there’d be a huge hole in my life—and in the nation’s—if they didn’t happen. What’s in that hole is what’s in the music Claire writes about—and the music often gets it better than even we writers can.