Penman for Sunday, August 10, 2025

AS A collector of many things old and wonderful—vintage fountain pens and typewriters, antiquarian books, and midcentury paintings—I occasionally come across the stray and even the strange object that I simply can’t say no to.

My wife and I are inveterate junkers—as I’ve often written about, we travel the world not to visit magnificent palaces, posh boutiques, or Michelin-starred restaurants. Rather, we dive right into a city’s flea markets, resale shops, and discount stores to see what treasures could be had for a song.

But travel costs money, so the next best thing is to go to the Web for the online equivalent of flea markets, among which there’s none larger than eBay, with millions of items on sale at any given minute. Having been on eBay almost since it opened 30 years ago, and with a feedback score over 1,500 (100% positive), I practically live in it, checking out its offerings several times a day, using targeted searches for certain pens, old books, and Filipiniana.

You’d be surprised how much Philippine material exists out there. I’ve repatriated paintings, maps, magazines, engravings, and such, feeling it my patriotic duty to bring them home. I have collector-friends scouring eBay just as diligently for Philippine medals, coins, stamps, and postcards—the results of which often turn up on our own auction sites, sometimes for millions.

Another virtual flea market that junkers like me habitually visit is the Facebook Marketplace. Facebook is full of selling groups devoted to everything from antiques, collectibles, and furniture to used clothes, fake gold bars, and broken appliances. They all end up at the Marketplace—which, frankly, was the principal reason I finally went on FB, after resisting for many years. I didn’t want to make friends and influence people—I wanted to shop for cheap gadgets like used iPhones and Apple laptops (both of which I’ve bought on FB many times) as well as the odd collectible, like the 1897 two-volume facsimile edition of Don Quixote that I picked up at a Jollibee, and a large pastel seminude by the modern Japanese master Ryohei Koiso.

But as with eBay, and because we’re right at home, nothing interests me more on FB Marketplace than Philippine material, and just this past month two outstanding discoveries reminded me why I should keep an eye out for the good, the strange, and the beautiful.

The first was a stunningly lovely picture of a Filipino woman in native dress, apparently from before the war. The dress seemed to have been colorized, but by hand and not digitally as we often find these days.

As soon as I saw that picture on FB, I knew that I had to have it (or to put it more nicely, I knew I had to get it for Beng). The seller posted it as an “acrylic on board from the 1950s,” which I wondered about but was just barely possible, with acrylic paint beginning to be used in the 1940s. (All the seller could tell me was that it had come from an old house in Sampaloc, and that he had nicknamed her Esther.)

It could have been a modern giclée print or a lithograph, but assured that it was indeed a painting under glass—the seller was highly reputable and lived just 15 minutes away from me—I took a chance and asked how much. Given a quote just in the four figures (I was expecting something significantly higher), I instantly “mined” it, as they say on the Marketplace.

When it arrived, Beng and I couldn’t believe our luck. It was large and gorgeous, but what medium was it? The painting was under glass, and we could see the paint strokes but not discern the texture of canvas. There were some mold spots under the glass, and some adhesions (this is where it pays to be married to an art restorer who has done all the Philippine masters from Luna and Hidalgo to Amorsolo and Magsaysay-Ho). Beng looked more closely at the face of the woman and, informed by her practice, realized what it was—a foto-óleo!

It was a new word for me, which of course I looked up. Google’s AI Overview had more to say about the technique behind the picture:

“Foto-óleo refers to a technique of hand-painting oil colors onto black and white photographs to enhance their appearance, making them more lifelike and visually appealing. This practice was popular in the Philippines during the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries, particularly in portraiture before the widespread use of color photography. According to the National Museum of the Philippines, it was a way for families, especially those of middle-class and prominent backgrounds, to signify their wealth and social standing. The National Museum of the Philippines and other institutions have collections of foto-óleos, some of which are displayed in exhibitions like ‘Larawan at Litrato: Foto-óleo and Picture Portraits in the Philippines (1891-1953)’.”

Before he let go of the picture, the seller asked me to take good care of his “Esther,” and we certainly will!

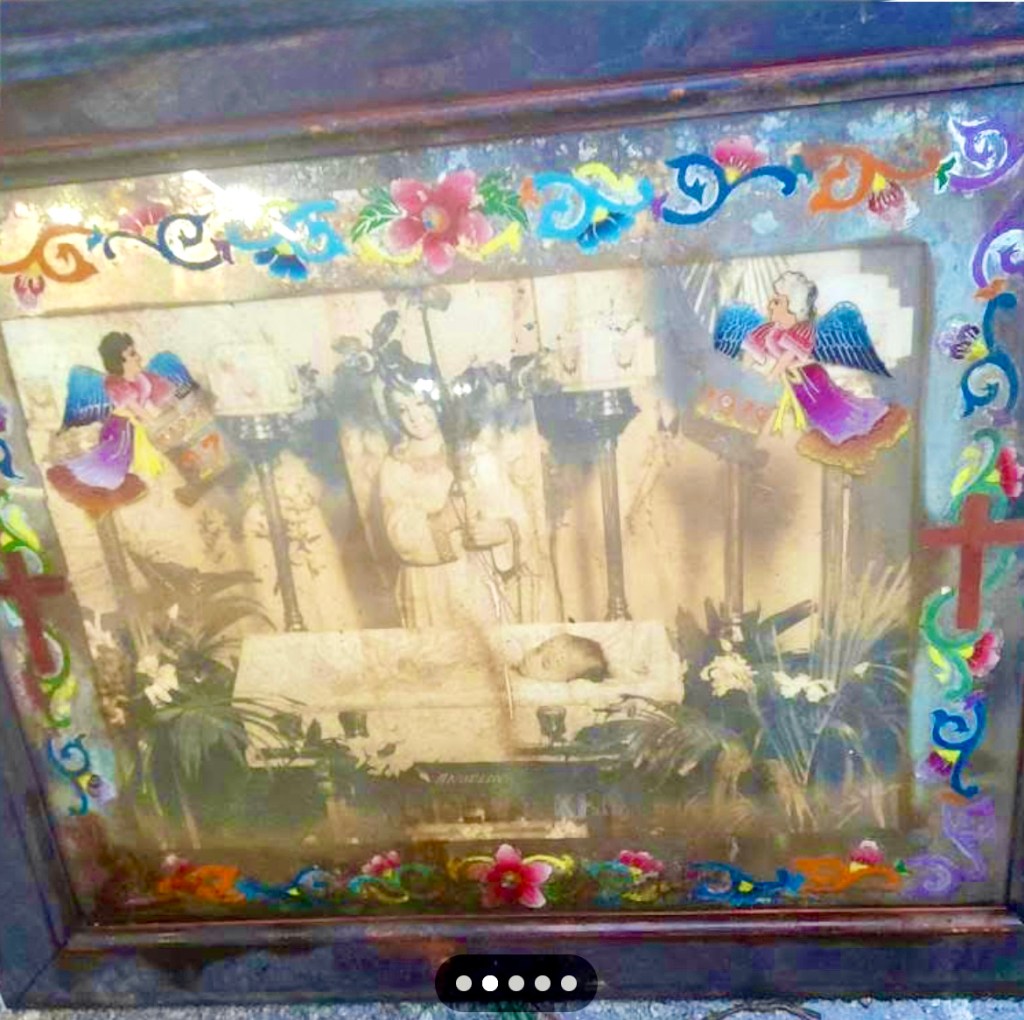

Just two days later arrived one of the most beautiful but also the saddest of my discoveries on FB Marketplace. My first reaction upon seeing it online—as might be any viewer’s—was a shudder of realization at what its subject was. But when I zoomed in on the details, I was soon taken and comforted by the care and love and the unspoken grief with which this child named Angela, whose passing on March 27, 1938 is marked, was sent off by her family.

These recuerdos de patay, as keepsake funeral pictures were then called, seemed more than a testament to the dead; they also exalted the living who cared enough to invoke the eternal watchfulness of glass-painted cherubs and angels over Angela.

And so began for Beng the task of restoring the funeral picture of young Angela. As the picture had presumably not been taken out of its frame for over 80 years, both the photograph and the glass were full of dust and grime. Hundreds of mold or age spots pimpled the surface.

The decorative border had been painted on the glass from the inside—but as Beng established after a quick solubility test, the painter didn’t use oil or enamel but likely tempera which dissolves in water, so she will have to be very careful to make sure its surprisingly vivid colors don’t come off. The narra frame will be cleaned and retained. It may be a morbid memento to some, but as art it gives Angela another life beyond March 27, 1938.

These two finds on FB Marketplace, heavy with emotion, reminded me that collecting sometimes goes beyond fun and profit. It involves respect and even reverence for a past that left us some brilliant images to remember it by.

Penman for Monday, August 5, 2019

Penman for Monday, August 5, 2019

I TOOK these shots of dried fish in Cebu some years ago–something ghostlike about them fascinated me.

I TOOK these shots of dried fish in Cebu some years ago–something ghostlike about them fascinated me.