Penman for Monday, September 26, 2016

I’D NEVER heard of Ramon Cualoping III and Marco Angelo Cabrera until their names were linked to the recent flap involving the use of no less than the Official Gazette in an apparent effort to sanitize the memory of Ferdinand E. Marcos by removing any reference to martial law—you know, the martial law that Marcos invoked to impose his dictatorial rule on his people from 1972 until he was deposed by a popular revolt in 1986. (Yes, he technically lifted martial law in 1981 but he continued to rule with a rubber-stamp legislature.)

Some Googling revealed that Cualoping was an Ateneo Communication Arts graduate, batch 2004, while Cabrera graduated from San Beda in 2013 and interned briefly with the Department of Foreign Affairs; he had also worked for Sen. Bongbong Marcos. Those are both fine backgrounds for jobs at the Presidential Communications Operations Office—just the kind of posting on which many young writers and lawyers aspiring for a political future have cut their teeth—and I can surmise from the dates provided that Messrs. Cualoping and Cabrera must be in their mid-30s and mid-20s, respectively—too young, therefore, to have personally known what the Gazette expunged.

In the interest of full disclosure, I was a government propagandist myself at an even younger age—19, fresh out of martial law prison. Having dropped out of UP and having worked for the Philippines Herald and Taliba just before martial law, I got a job with the PR section of the National Economic and Development Authority. The irony of going from writing incendiary flyers to trumpeting such new government projects as Pantabangan Dam wasn’t lost on me. But I was getting married and needed a job, and all the old media jobs were gone save for the Express and the Bulletin, so I was thankful for whatever came my way. (I would much later write hundreds of speeches for FVR, among other Presidents and political clients—mostly to pay the rent, occasionally for the sheer privilege—so don’t look at me as some crusading journalist.)

I don’t know what drove Messrs. Cualoping and Cabrera to the Palace; I’m assuming their motives were loftier than mine. I also don’t know what made them officially forget (hey, it’s the Official Gazette, right?) that FM declared martial law. I suspect they knew what happened, but chose to ignore the most salient fact about Marcos’ life, for reasons only they can tell. To his credit, Communications Secretary Martin Andanar effectively reprimanded his staff for the deliberate oversight and corrected the record.

I’ll leave further chastisement of these two gentlemen to the netizens who broke the story. From one PR pro to another, what I can tell them is this: I understand the job you have to do and even your private allegiances, but there are things—very big things much bigger than yourselves—that you just can’t sweep under the rug. Denying martial law or its disastrous effects on our society and economy is like telling Jews that the Holocaust never happened, or was actually a good thing. I salute you for your cheek, but what on earth were you thinking?

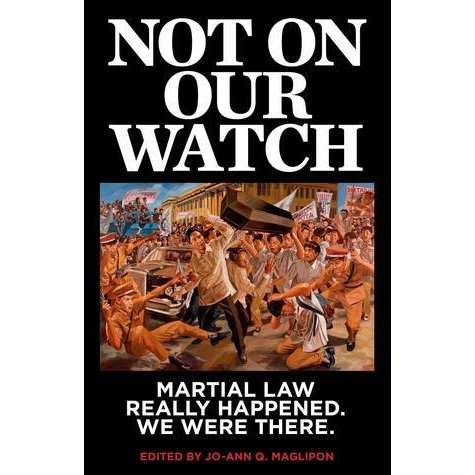

There’s a book I’d like to recommend to these two, one which I and a dozen other writers—all students during martial law—put out four years ago on the 40th anniversary of Proclamation 1081, titled Not on Our Watch: Martial Law Really Happened, We Were There. (For more on that book, see here: http://www.philstar.com/sunday-life/806191/lest-we-forget.) I wasn’t too enamored of the long title at that time, but now I appreciate the emphatic clarity of the thing; it’s just the sort of book martial law amnesiacs and deniers need to read.

But even as we review history, there’s one thing that seems to have escaped many: the current debate about how to look at martial law and where to bury Ferdinand Marcos isn’t about the past; it’s about the future, and what kind of people we are and want to be.

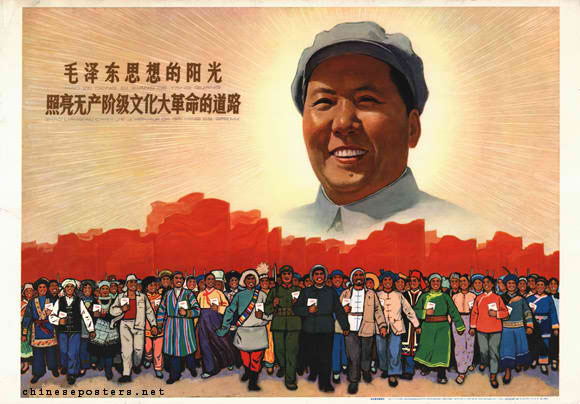

I know that millennials tend to get beat up on because they don’t know enough about martial law, which is hardly their fault since we didn’t teach them enough about it. But it isn’t just them. When people my age express bewilderment over how Bongbong Marcos came so close to becoming Vice President despite his dad’s misdeeds, and how the Marcoses have survived so handsomely, I have to remind them that even under martial law, those of us who opposed Marcos were in the distinct minority. Most Filipinos supported martial law, actively or passively, or it wouldn’t have lasted so long. Like the Germans who supported Hitler, most Filipinos stood by while we faced the truncheons and firehoses—and even applauded 1081, early on, as the antidote to Communism (1972’s “war on drugs”). So what should we be so surprised about?

That’s why I’ve never referred to EDSA 1 as a revolution, because it wasn’t one in terms of changing anything fundamental in the structures and workings of our society. It was a popular uprising, a street revolt led by another faction of the ruling class, with broad support from the metropolitan middle class. That doesn’t mean I didn’t feel euphoric that February, and I still get teary-eyed when I remember the moment; I guess the poignancy comes from knowing what came afterward.

I have no doubt that if the Palace incumbent were to declare martial law today for whatever reason, a majority of Filipinos would support him, although a noisy few of us would be up in arms. Martial law ca. 1972 was also like that, and remained popular for many more years, especially among amoral businessmen who sang its praises until it hit them in the pocket. And then it all went downhill.

Contrary to what you might expect, I don’t see Marcos as a one-eyed ogre, but rather as a calculating Macbeth, keenly aware of his actions and perhaps even troubled by them. In my own turn with revisionism, I’ve even managed to convince myself—as I told the BBC in a recent interview on EDSA (a part which never got aired for lack of time)—that Ferdinand Marcos may have done us a final act of kindness by leaving without ordering a bloodbath. It’s an arguable notion (one I wouldn’t put on the Official Gazette) and it doesn’t change the fact that his regime took what it could until we bled, but as a fictionist and playwright, I like to imagine characters to be more complex than they seem.

A couple of years ago, at a cultural function in Quezon City, Mrs. Marcos preceded me by a few steps down a narrow staircase. She was clearly having a hard time navigating the stairs, and she looked back at me apologetically to say, “Hijo, I’m very sorry I’m keeping you.” I smiled and said, “It’s all right, Ma’am, please take your time.” I felt amused and strangely triumphant.

History is sometimes best seen as a series of comic and tragic ironies, which straight journalism and certainly government tabloids can’t dispense. Come to think of it, who gives a hoot about the Official Gazette? If you want to lie and get away with it, try fiction. I’d be happy to see Messrs. Cualoping and Cabrera in my graduate workshop.

Penman for Monday, January 26, 2015

Penman for Monday, January 26, 2015 Penman for Monday, January 5, 2015

Penman for Monday, January 5, 2015