Qwertyman for Monday, May 19, 2025

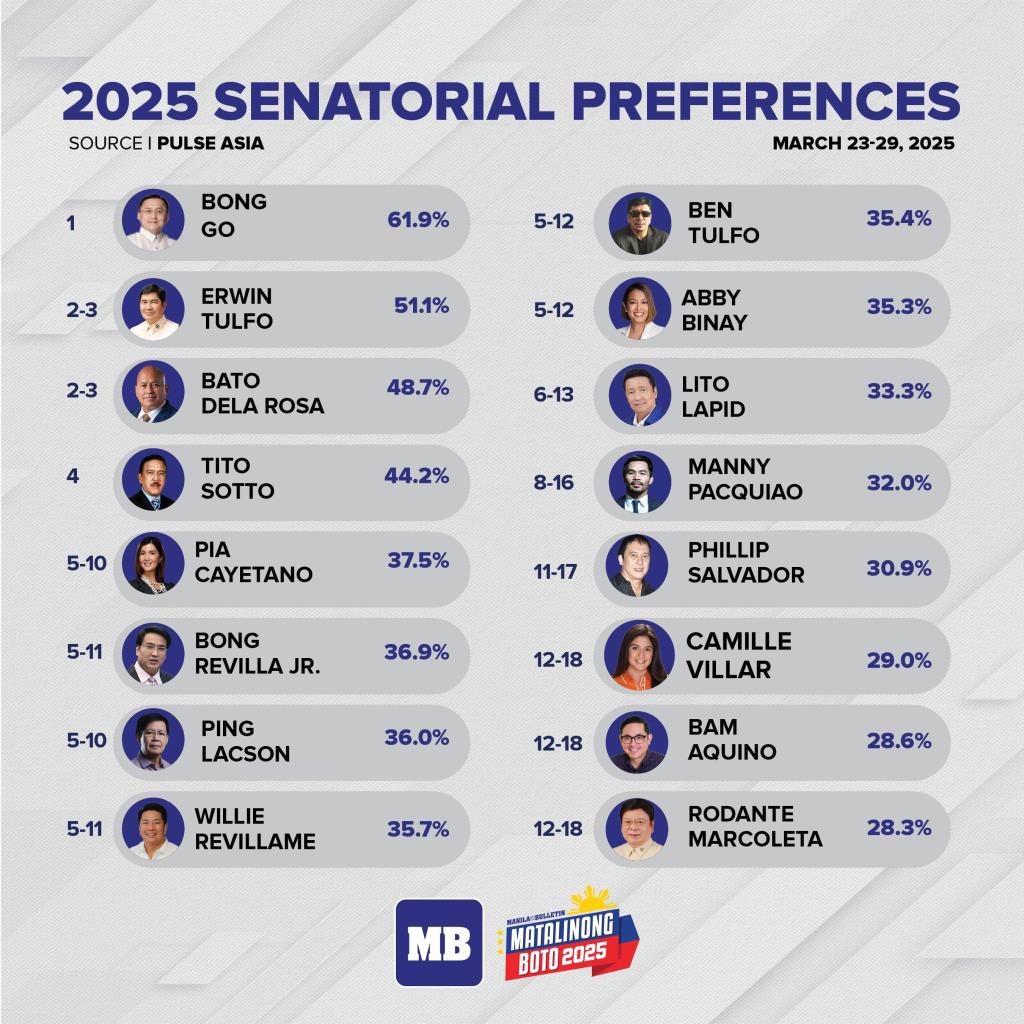

THE PUNDITS have spoken and all kinds of analyses have been made about the recently concluded midterm elections, with most observers remarking on the surprise victories of Bam Aquino and Francis Pangilinan in the Senate and of Akbayan and ML in the partylist, as well as the steep decline of the hard Left alongside the continuing strength of the pro-Duterte forces.

Some read the results as a sharp repudiation of the administration, others as a resurgence of the “Pinklawan” moderates, and yet others as just more proof of the Pinoy voter’s kabobohan in keeping the same old names in power. What’s clear is that it was a mixed outcome, giving everyone something to either crow or complain about.

At my favorite poker haunt, where I’ve been playing with a bunch of regulars for nearly twenty years, the table talk inevitably came around to the election results. The people here—mostly young and but with many seniors, mostly men, mostly middle class and urban (you need some money to play poker)—represent for me a good cross-section of our society, perhaps statistically imperfect but more grounded in gritty reality: neither scholars nor ideologues but homeboys coming from both Manila and the far provinces, brought together by nothing grander than chasing after a straight flush and pocket aces.

Maybe to rattle their opponents or to deflect attention from the cards, these guys can talk up a storm about politics. My general strategy is to shut up and smile to keep them guessing; although they know me as a UP professor and could presume on my liberalism, I’ve decided that listening rather than arguing would yield me a truer picture of the Pinoy mind, and protect my hand.

Back in 2022—to my great dismay—that mind was overwhelmingly pro-“Uniteam.” Despite all the information floating out there about Marcosian martial law and Dutertean bloodlust, my fellow pokeristas and even the dealers loudly proclaimed that they were voting for BBM, hushing the few Kakampinks in the room.

Last week, the atmosphere in the poker place was decidedly different, one of great amazement and relief. There was surprise–but also joy—that Bam and Kiko won. The biggest buzz revolved around Pasig City Mayor Vico Sotto, less over the win that everyone expected than his political future, which everyone agreed should include the Senate and at least the vice presidency, the only concern being his youth (not that he was too young for the job, but for the legal minimum age). No tears were shed over the loss of popular entertainers and media personalities. Not much was said about BBM and VP Sara, who seemed strangely irrelevant, despite the fact that the midterms were effectively a proxy war between them.

Now of course you could say that a gambling den is hardly representative of the Filipino people, but then gamblers are among the most hardboiled cynics you can find, not easily given to idle wonderment. (And then again, poker wouldn’t thrive without foolishly hopeful patsies like me—called “fish”—who go all-in on a pair of deuces, hoping to catch a trio. Remember Anton Chekhov’s description of gamblers as people who “go out for their daily dose of injustice.”) That a shift in the tide seemed to ripple on the surface of these poker faces was encouraging. I suspect that these dehadista sentiments were there all along—but have now been emboldened to surface, and I can see this happening all over the country: it’s okay to hope, to bet on the long shot.

It’s probably a measure of how desperate we’d become, more than anything else, that progressives all over the country are ecstatic to have won two out of 12 seats in the senatorial race, never mind that the other winners were mostly your usual crowd of trapos and Family Feud participants.

After previous wipeouts and defeats that, we were convinced, only massive fraud could have engineered, these signal victories—along with a smattering of other partylist and local wins—have now raised our hopes for a more enlightened electorate and a resurgent opposition.

The question is, who will that opposition be, and who and what will it be opposing? Frozen out of the Palace and facing impeachment, VP Sara has claimed the mantle of opposition leader in her post-election statement. That’s “opposition” in the trapo sense of the word—another faction of the same ruling elite, another version of greed and lust for power.

It should be clear by now that a real, viable, and electable opposition can come only from the middle forces that are beginning to regain their footing after the hard loss of 2022. The sad but not surprising defeat of the more radical Gabriela and Bayan Muna partylist groups—which some see as the triumph of Red-tagging—puts the burden of the fight against corruption and for good governance on Bam Aquino, Kiko Pangilinan, Risa Hontiveros & Co., because it’s something that no one else in the government, certainly not the Dutertites, have the moral authority to undertake.

For this battle, and in preparation for 2028, this opposition has to adopt and master coalition politics—or rather their supporters have to learn how to unite, to maintain focus on the big picture, and to yield ground when necessary for the greater good.

For example, as I noted in an FB comment, Luke Espiritu and Heidi Mendoza turned in good performances—but they could have been better if some of our “liberal”-minded friends didn’t junk them on single issues: Luke for supposedly being an “abortionist” and Heidi for being a “homophobe.” Until we can get beyond our enclaves and agree on broader issues, the real evil will win. Sometimes we look for perfect candidates, people who align with all our principles, check all the boxes, lead blameless lives. But everyone’s flawed—any writer from the Greek playwrights onward knows that.

We hand-wringers can be our own worst enemies. As a recent opinion piece in the New York Times put it, “Members of the educated elite… tend to operate by analysis, not instinct, which renders them slow-footed in comparison to the Trumps of the world…. Such elites sometimes assume that if they can persuade themselves that they are morally superior, then that in itself constitutes victory; it’s all they need to do.”

We have three years to see what was really achieved in May 2025, and if, like a good pokerista, our middle forces will know how to play a weak hand from a strong position, with a single-minded audacity and resolve.