Penman for Sunday, July 13, 2025

AS A collector (make that a scavenger) of old books, manuscripts, and what the market generally calls “ephemera,” I inevitably come across material neither written by nor meant for kings and presidents, but rather pedestrians like myself with things to say, perhaps secrets to whisper, likely to no one but to God and posterity.

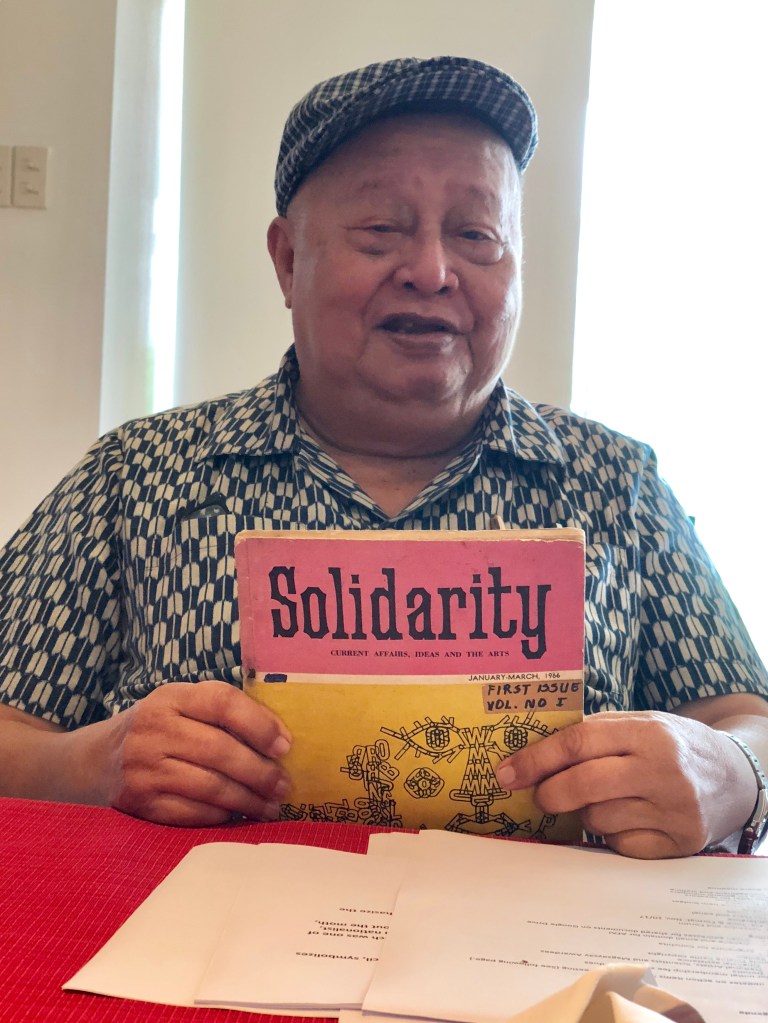

I’m talking about diaries and journals, which people of my generation used to do (and millennials are back to doing). Worse than a pack rat, I hoard other people’s memories, some in diaries that would make people turn in their graves to know I had. I come across these often as discards or stray items among people selling and buying old books, but I find them equally if not even more fascinating than published (and therefore sanitized) material.

Back then, before computers and digital journals, New Year began with the purchase of a new diary, its pristine pages waiting to be filled with birthdays, appointments, expenses—and more interestingly, interjections of love, pain, joy, and grief, life’s highest and lowest moments.

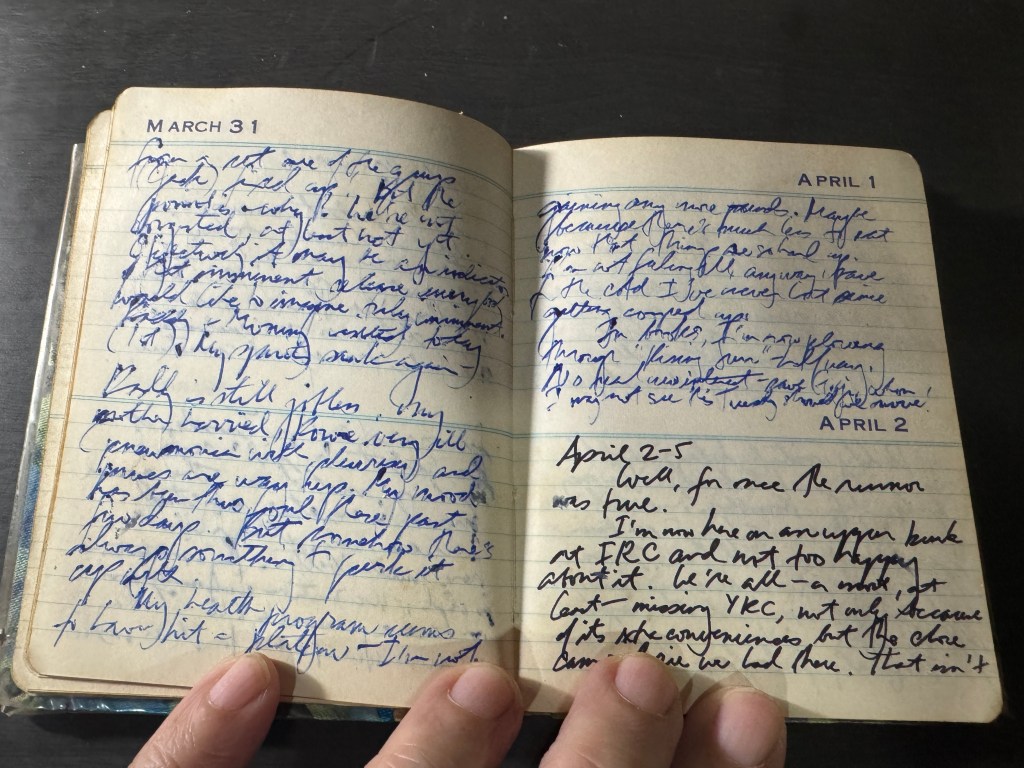

I myself kept diaries at one time, although the entries tended to peter out around March or April, when fatigue got the better of my enthusiasm. My most interesting one has to be my martial-law diary, which I rather presumptuously began as soon as I was thrown in prison at Fort Bonifacio; I say “presumptuously” because, at seventeen, I entertained the precious thought that somehow, someday, my juvenile musings would be worth something to someone other than my mother (I had yet to find a wife then).

When the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci languished in a Fascist jail in the late 1920s, presumably between a meager breakfast and gazing out into the starless night, he penned lines like “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.” He developed his theory of hegemony and held forth on the role of intellectuals in social change, published in his seminal Prison Notebooks.

My own teenage memoirs have survived, but instead of writing about the dominance of the ruling class or about harrowing details of torture and misery—which did happen to others—I chronicled the visits of the pretty young psychologists assigned by the military to interview us; of course we assumed they were spies, but that didn’t stop us from chatting with (more like staring at) them across a table that felt much too wide.

Indeed, for most of us more interested in the personal than the political (although arguably one will always be the other), the value of diaries lies in their true confessions, in their promise of intimacy and insight—along with, let’s admit it, the wicked thrill of voyeurism.

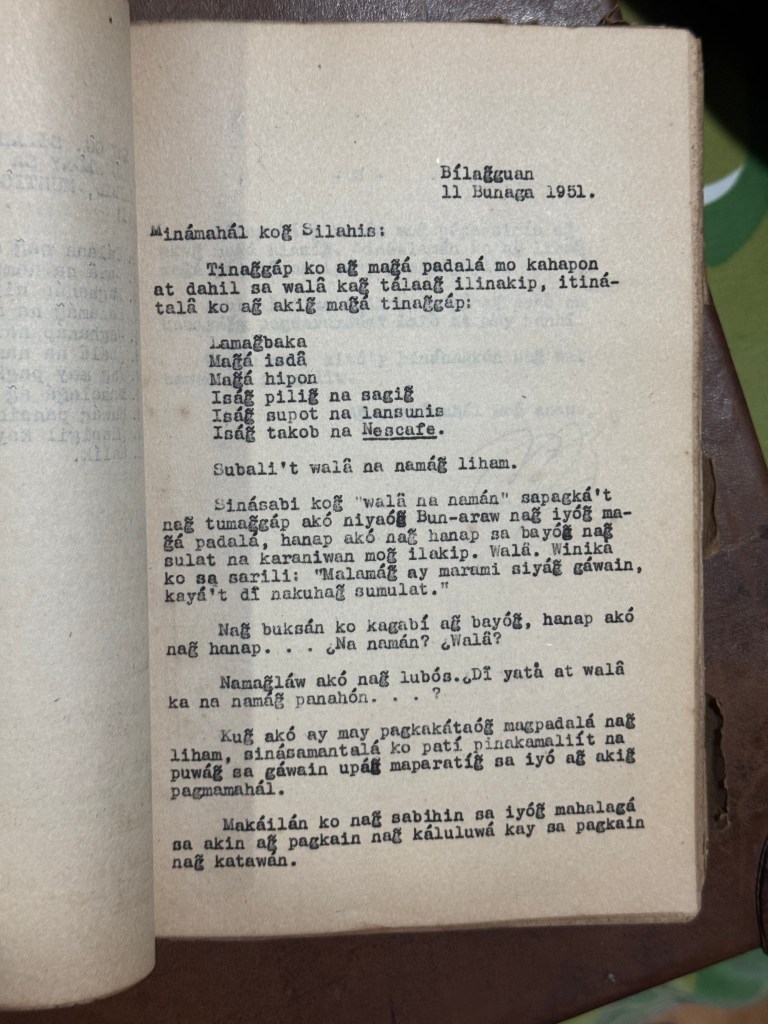

Among the most poignant of my inadvertent discoveries has been the diary—really more a scrapbook—of a once-famous and gifted writer (whose name I’ll leave out for now as he still has family around) who was imprisoned after the War for his stridently pro-Japanese sentiments and actions. In three languages, both typewritten and handwritten, he acknowledges receipt of his beloved’s supplemental rations—beef, fish, fruits, and coffee—but no letter yet again. “Nang buksan ko kagabi ang bayong, hanap ako nang hanap…. Na naman? Wala? Namanglaw ako nang lubos. Di yata at wala ka na naming panahon.” How many times do I have to tell you, he goes on to lament, that even for important to me than sustenance for my body is sustenance for my spirit?

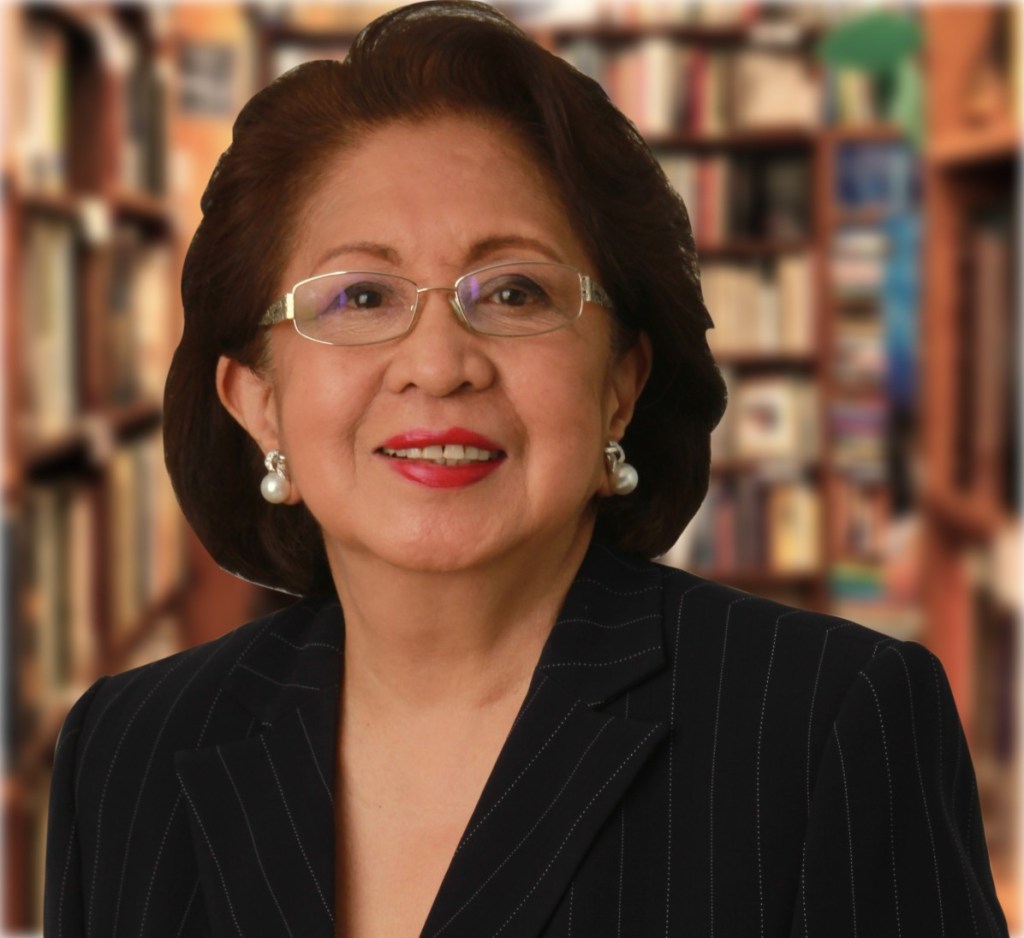

I once came across a whole sheaf of journals in a ditch in front of our house, which I was inspecting because it had gotten clogged with what turned out to be a plastic bag full of papers. It had been carelessly thrown there by the home’s previous occupants or whoever cleaned it out—we had just moved in. They turned out to be the personal papers of a renowned UP professor, and as guilty as I felt about peeking into her life, I read a few pages, in which she confessed her admiration for a certain man (she lived and died a spinster)—only to remind herself, with what I could almost hear was a deep sigh of regret, that she considered herself wedded to God. I read no further, and decided to turn the papers over to a friend, a former and beloved student of hers who was the closest thing to a son.

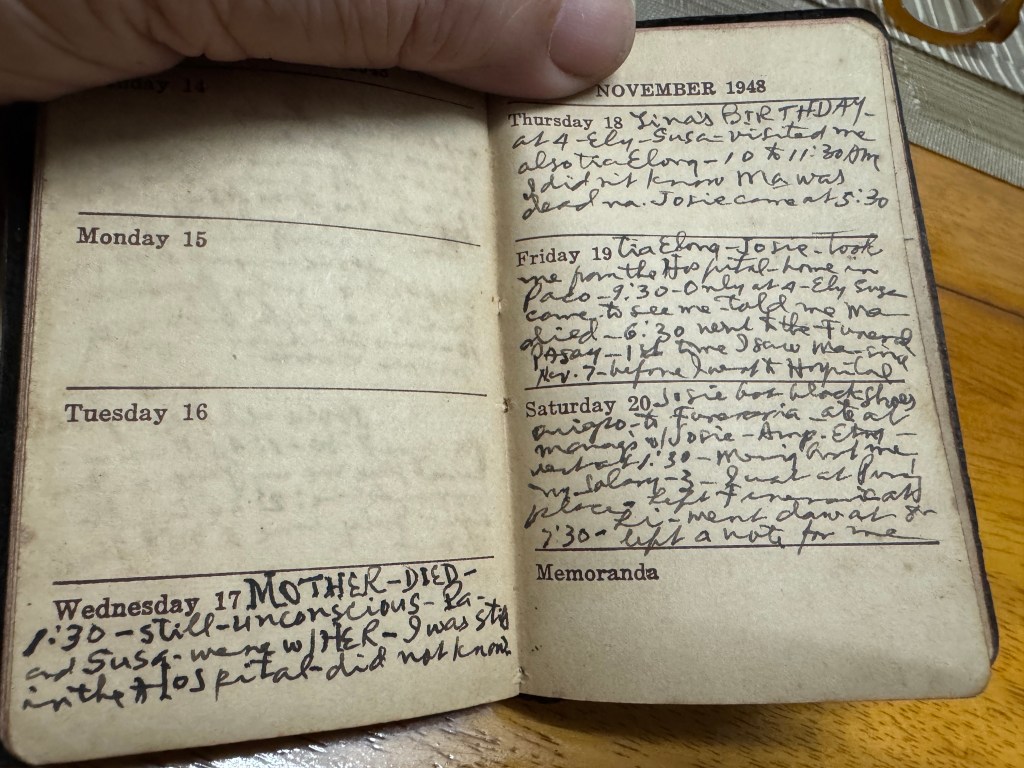

Most recently, some diaries from the late 1930s and 1940s came to me along with a medical book, and they contain nothing so revelatory, but the details of everyday life a,re always engrossing. They obviously belonged to a doctor—perhaps more than one—and while they contain medical marginalia they also carry legal notes, so the owner must have been studying to be a medico-legal person. Rather moving is the narrative in one diary of bringing a very sick mother to the hospital; I flipped a few pages and the inevitable entry appeared: “Mother died.” And there lay the stark helplessness of a doctor who could not save his own mother.

For many years now, the writer and presidential historian Manolo Quezon has been on top of an important enterprise called the Philippine Diary Project, a digitized compilation of diaries and memoirs from such notables as Jose Rizal, Ferdinand E. Marcos, Dean Worcester, and Emilio Aguinaldo all the way to the murdered activist Ericson Acosta (clearly more women need to be added to the roster).

“To me there are two holy grails,” Manolo told me. “The first is the diary of Gregorio H. Del Pilar. The diary of the American officer who led the expedition that killed him, Frederick Funston, exists but has yet to be transcribed. It was he, by all accounts, who pocketed del Pilar’s pocket diary; perhaps his papers will reveal them after a thorough search. The other is the diary of Benigno S. Aquino, Sr. The late Benito Legarda, Jr. told me that it was shown to him by one of the sisters of Ninoy, and that, in Spanish, it began, “I have been summoned to a meeting in Malacañan by the commanding general of the Japanese Military Administration…” The thing is, the last sister who had it, lost her memory and her children have not found the diary since.”

He adds that “A large portion of the Marcos diary is missing and anecdotally is said to be in the possession of a former member of his administration. For me though, what I’m seeking are diaries by Filipinos. Our own voices are woefully underrepresented. I think many were lost in Ondoy, many others have been thrown away, still more exist, but families are afraid people will take offense and so prefer to keep them secret.”

What I find from my own small collection is that whether they wrote in English or Tagalog, or used fountain pens or typewriters, our forebears recorded the smallest details such as “Auto repair 15.00” and “Won jai-alai 5-3 event.” Today we do all that with digital ink. I wonder what some digital pack rat will be remarking about us 50 years hence.