Penman for Sunday, January 4, 2026

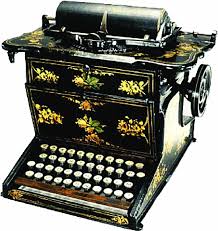

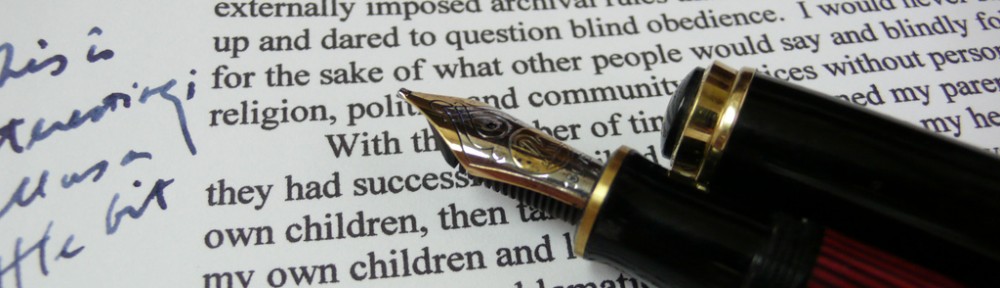

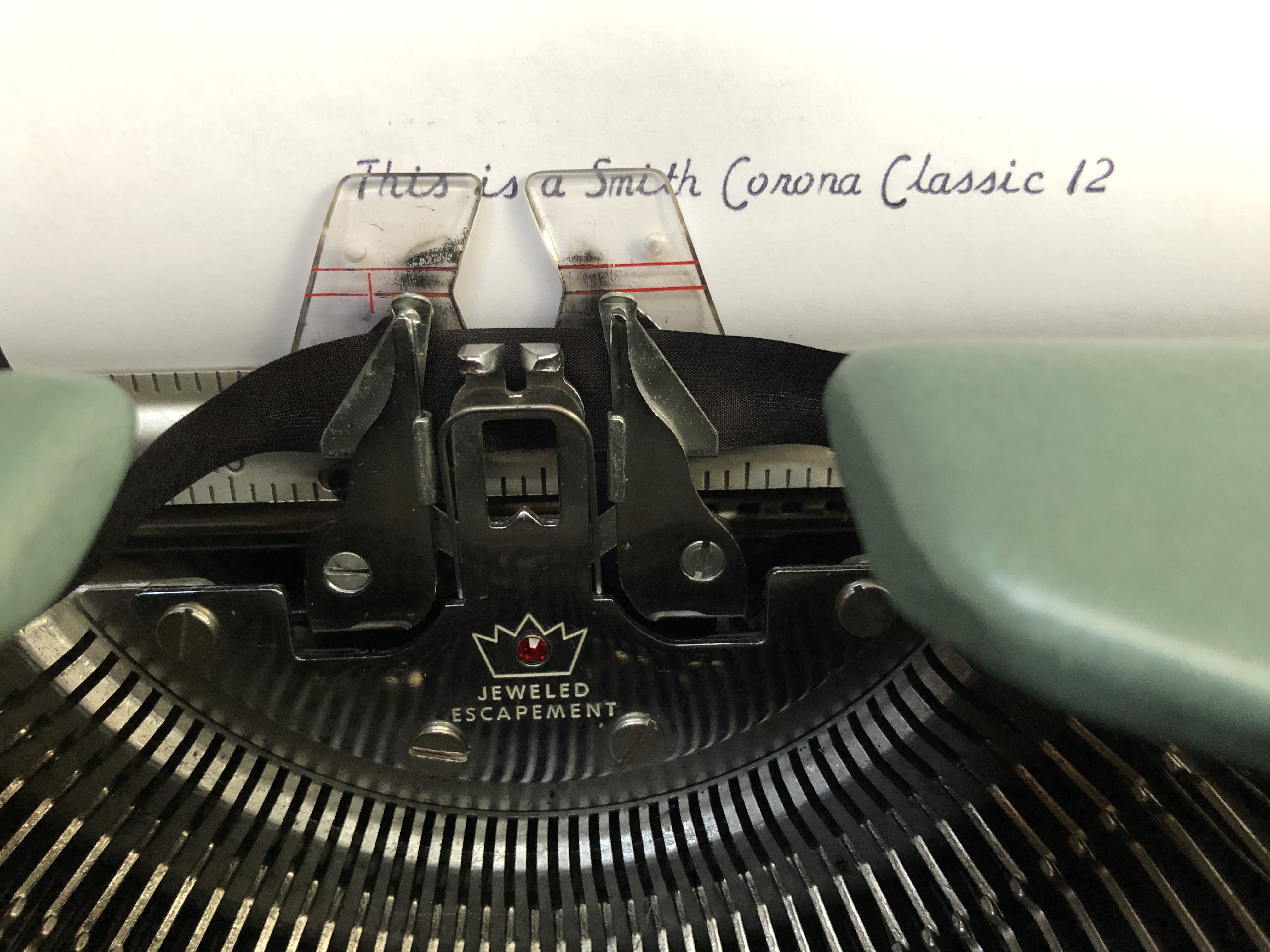

MAYBE BECAUSE of the name I chose for it, longtime followers of this column which I began more than 25 years ago will associate me with collecting vintage fountain pens, and they’d be right—partly. That’s because while I continue to collect pens with a passion, I’ve since branched out in half a dozen other directions, including typewriters, blotters, antiquarian books, midcentury paintings, canes, and even silver spoons.

It’s the kind of behavior that drives collectors’ wives crazy (although I’ll have more to say about the gender issue later), and I can only be thankful that my wife Beng has indulged me all these years. Beng collects bottles, tin cans, and pens herself, but nowhere near the intensity with which I check out eBay three times a day, scour the FB Marketplace, converse in geek-speak with fellow collectors, and subject my collections to never-ending cataloguing.

Seventeen years ago, some twenty people who must have thought they were the only ones interested in fountain pens met in our front yard in UP to form the Fountain Pen Network-Philippines. Those twenty have since grown to over 15,000 members on our FPN-P Facebook page. Unusually among hobbyist groups, and despite its explosive growth, FPN-P has remained one of the Internet’s friendliest and safest spaces, thanks to strict moderation and its openness to all kinds of pens and members, whether they come in with P100 pens from Temu or six-figure Montblancs (yes, there are Rolexes in pendom, although pens are far more pocket-friendly than watches).

One natural offshoot of FPN-P’s expansion has been the emergence of sub-interest groups, among which is the “PlumaLuma” group, which began as one devoted to vintage pens and desk accessories, but which soon evolved into “PlumaLuma Atbp.” as it became clear that pens weren’t our only obsession.

Some collectors maintain a clear and strict focus, like watches, santos, and tea sets. Others branch out into tangential areas (like other writing instruments and books and ephemera for me). The latter far outnumber the former, as collectors soon realize that one is never enough—not just of an object, but of collectibles. There are also “completists” who must have every single item known to have existed, catalogued and off-catalogue, in every collecting band (among my vintage Parker pens, for example, I have about 80 “Vacumatics” from the 1930s and 1940s—still far short of the hundreds of variants made).

Any serious collector in any field will tell you that a good collection takes more than money—although money surely matters in the rarefied realms. What’s just as important is connoisseurship—knowing what to want and why, and understanding the market. For budget-challenged collectors like me, knowledge and determination help balance out the odds, allowing me to buy low, sell high, and eventually trade up to the best goods without paying MSRPs. That also means taking more risks on places like eBay, but then there’s the thrill and pleasure of the hunt, which stepping into a boutique and plunking down a credit card simply can’t buy.

Those of us who collect vintage and antique items (by convention, “vintage” means at least fifty years and “antique” at least a century old) take even more risks , because what we collect could be damaged, stolen, or even fake. With the rise of auction houses and the allure of parking one’s money in some conversation-piece or status-symbol artifact, the stakes have risen even higher; there have been reports, for example, of forged master paintings sold and of “rare” coins being doctored to acquire more value at the auctions.

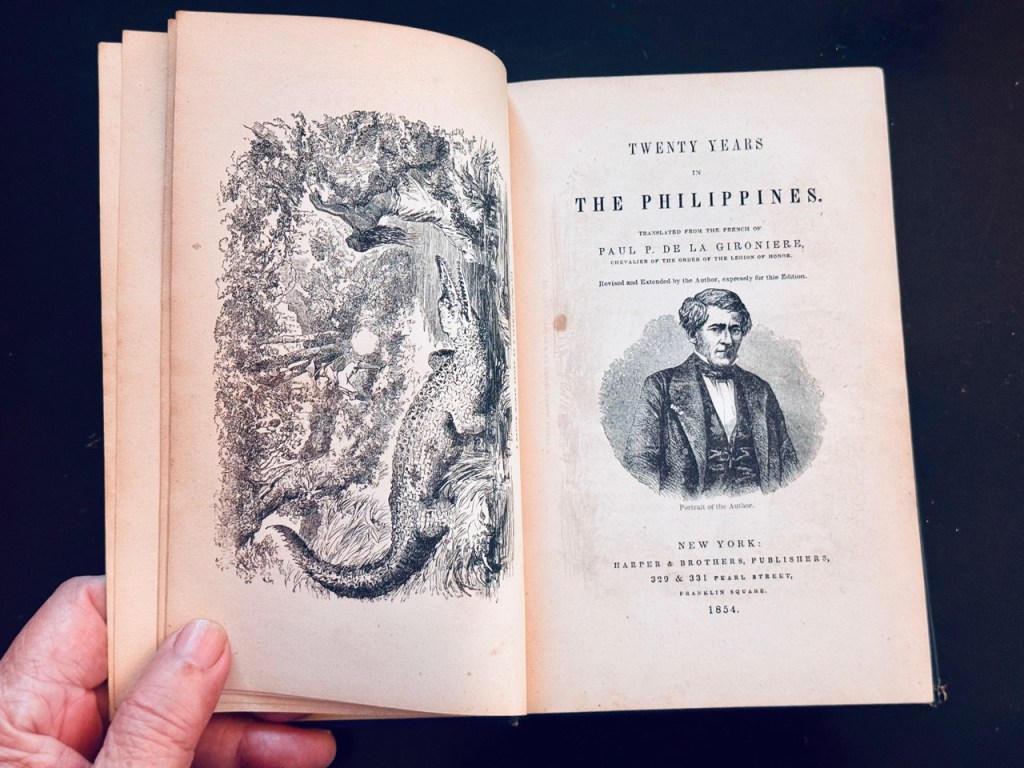

None of this has daunted the fatally bug-bitten collector, for whom the bar has simply risen; the Internet and the emergence of collecting groups has enlarged the competition, but at the same time it has opened more markets (I’ve bought pens and rare Filipiniana from as far as Bulgaria and Argentina).

That explains the amazing range you’re about to see in the collections of four gentlemen I’ve picked out from PlumaLuma Atbp. who exemplify, for me, the finest in collecting and connoisseurship, being virtual walking encyclopedias of their particular specialties. (And to clarify an earlier point, PlumaLuma has many lady members with formidable pen collections—lawyer Yen Ocampo and cardiologist Abigail Te-Rosano among them—but despite what’s been said about women and shopping, they don’t seem to be anywhere near as profligate as most of these men.)

The exception to the charge of profligacy (to which I will readily confess) is Raphael “Raph” Camposagrado. Barely in his thirties, Raph trained in the UK and often travels to Europe as a software and AI consultant, imbibing Old World culture with keen devotion. He is the model of collecting focus and discipline, keeping his world-class collection of vintage fountain pens within clear numerical bounds. The one thing they have to be, aside from being old, is beautiful—as in Art Deco beautiful. No pen epitomizes that more than the 1930s Wahl Eversharp Coronet, as Raph explains:

“Considered the peak of Art Deco within the world of pen collecting, the Coronet is abundantly adorned with the symmetry, sharp angles, and geometric forms that enjoyers of the design movement obsess over. The cap and barrel are gold filled and strewn with longitudinal striations. Triangular red pyralin inserts and the pyramidal cap finial give a bold pop of color echoing the beams of search lights that would have streaked over 1930s Manhattanites. This particular piece is equipped with a slide adjuster that allows the user to change the stiffness of the nib from a firm writer of business letters to one with line variation for calligraphic pursuits. It even sports an ink view letting the user see if the pen is due for a refill. While modern pen making tends toward the large, gilded, and ornate, the Coronet achieves extravagance with just the right amount of restraint. It is golden without being a rococo explosion. It is diminutive and so maintains the dimensions of classic jewelry. It knows just how much to show like many other luxury pieces made in the late 1930s.”

Raph is also known for his sub-collection of exquisite desk pen sets, once the hallmark of executive success. The Wahl-Eversharp Doric sets, in particular, are visual stunners.

“I personally scoured Ebay to build a mini collection around this model by Wahl-Eversharp called the Doric,” says Raph. “Other than the Coronet, the Doric is quintessentially Art Deco, sporting twelve facets. The marble desk base is supported by a thin chrome bed and has bracing that reminds me of a hawk’s neck and beak when viewed from the front or back. The depth of the celluloid on the various pens looks as if it were of stone as natural as the desk base itself.”

Investment consultant Alexander “Sandy” Lichauco has long been known in the collecting world as a collector of Philippine medals and tokens, having co-authored a seminal book on it with Dr. Earl H0neycutt (Philippine Medals and Tokens 1780-2024). However, dismayed by the rampant commercialism in that hobby (forgeries and malpractices abound), Sandy turned to fountain pens, amassing an amazing vintage collection in less than two years (including many Parkers that I—his budolero—wish I had).

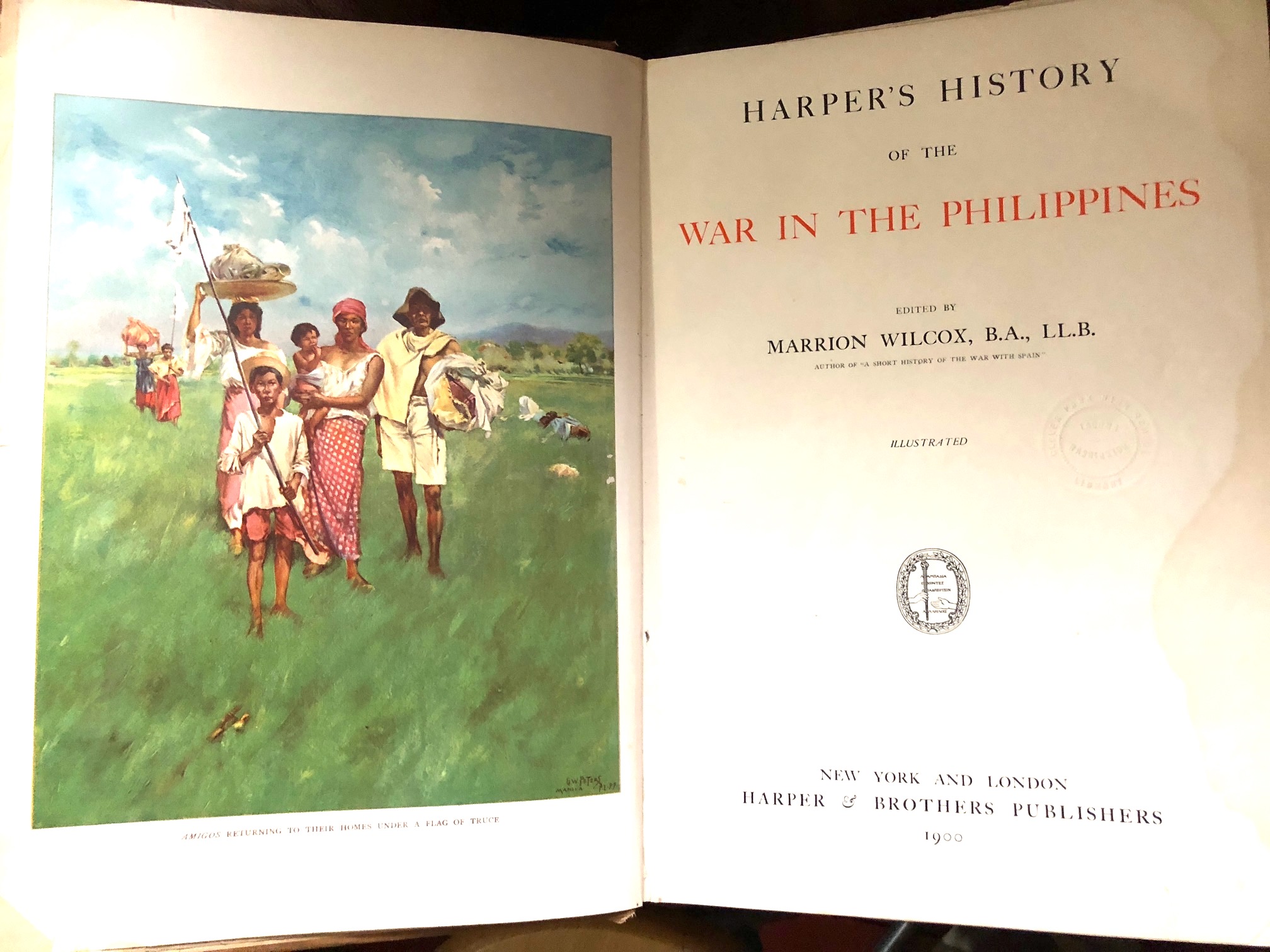

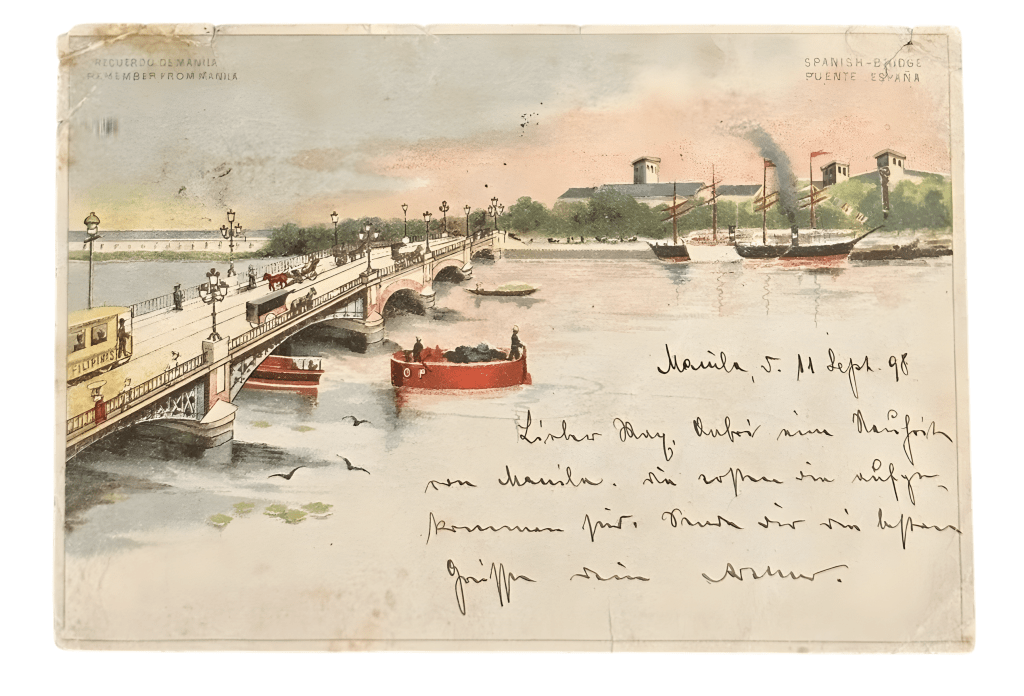

But aside from medals and pens, Sandy is also one of the country’s foremost deltiologists—that’s “postcard collector” to most of us. “I’m deep into deltiology now and have tracked down nearly 100 private mailing cards (which isn’t much compared to other collectors, but I’ve become very intentional and selective about these cards) from the turn of the century, including these two newly acquired color cards,” he says. “But the crown jewel is my 1898 Pioneer card of the Puente de España. I snagged it at a London auction, and I love the unique watercolor art. It’s postmarked and was used just three months after we gained our independence from Spain. It’s been on exhibit at the Ortigas Library since August.”

Sandy also maintains the highly informative and interesting blog www.nineteenkopongkopong.com (and he can explain the origin of that word).

When he’s not practicing his trade as a licensed architect and project and construction manager, Melvin Lam—our newest convert to fountain pens—collects historical artifacts and documents such as the silver quill pen given as a prize to the young Jose Rizal, a letter from Andres Bonifacio to Emilio Jacinto, 1st Republic revolutionary coins and banknotes, a photograph of Rizal’s execution, the 1898 Malolos menu, revolutionary flags from the First Republic, the Murillo Velarde map, and an Ah Tay bed, among many others.

Melvin is also an expert on the anting-anting, co-authoring the Catalogue of Philippine Silver Anting-Anting Medals. “My passion for history and culture was influenced by my father, Robert Lam, who began collecting antiques and artifacts in the 1970s. It has taken my family over 50 years to acquire our current collection. Our collection ranges from early prehistoric Philippine artifacts, items from the pre-colonial, Spanish colonial, American occupation, and Commonwealth eras, up to World War II Filipiniana items. It also includes antique anting-anting, antique santos, Philippine indigenous items, antique furniture, and Martaban jars.”

Not surprisingly, Melvin serves as president of the Bayanihan Collectors Club, known for its webinars, exhibits, auctions, and other historical celebrations, and as a board member of the Filipinas Collectibles and Antique Society (FCAS), which organizes international conventions for antiques and collectibles.

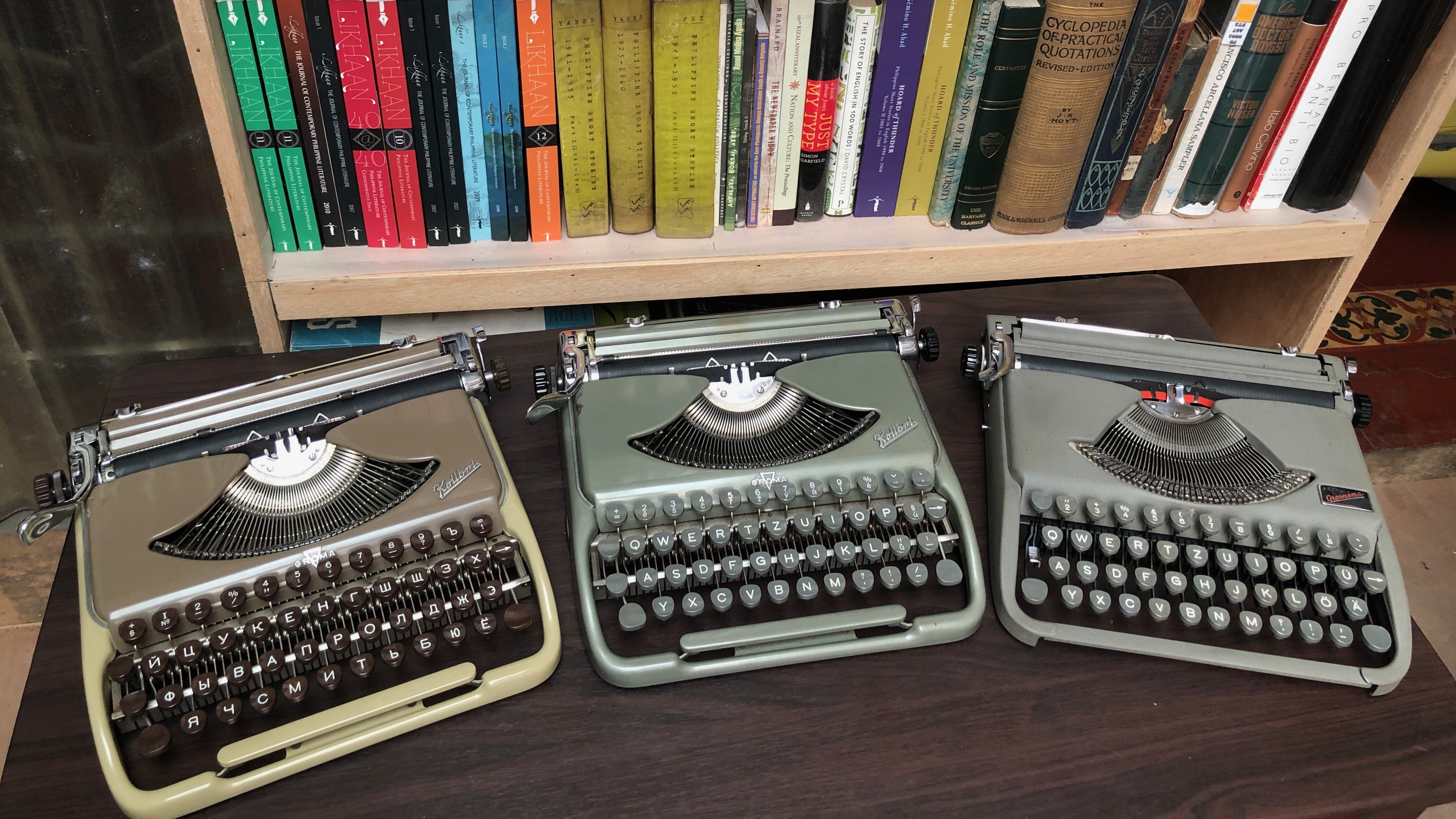

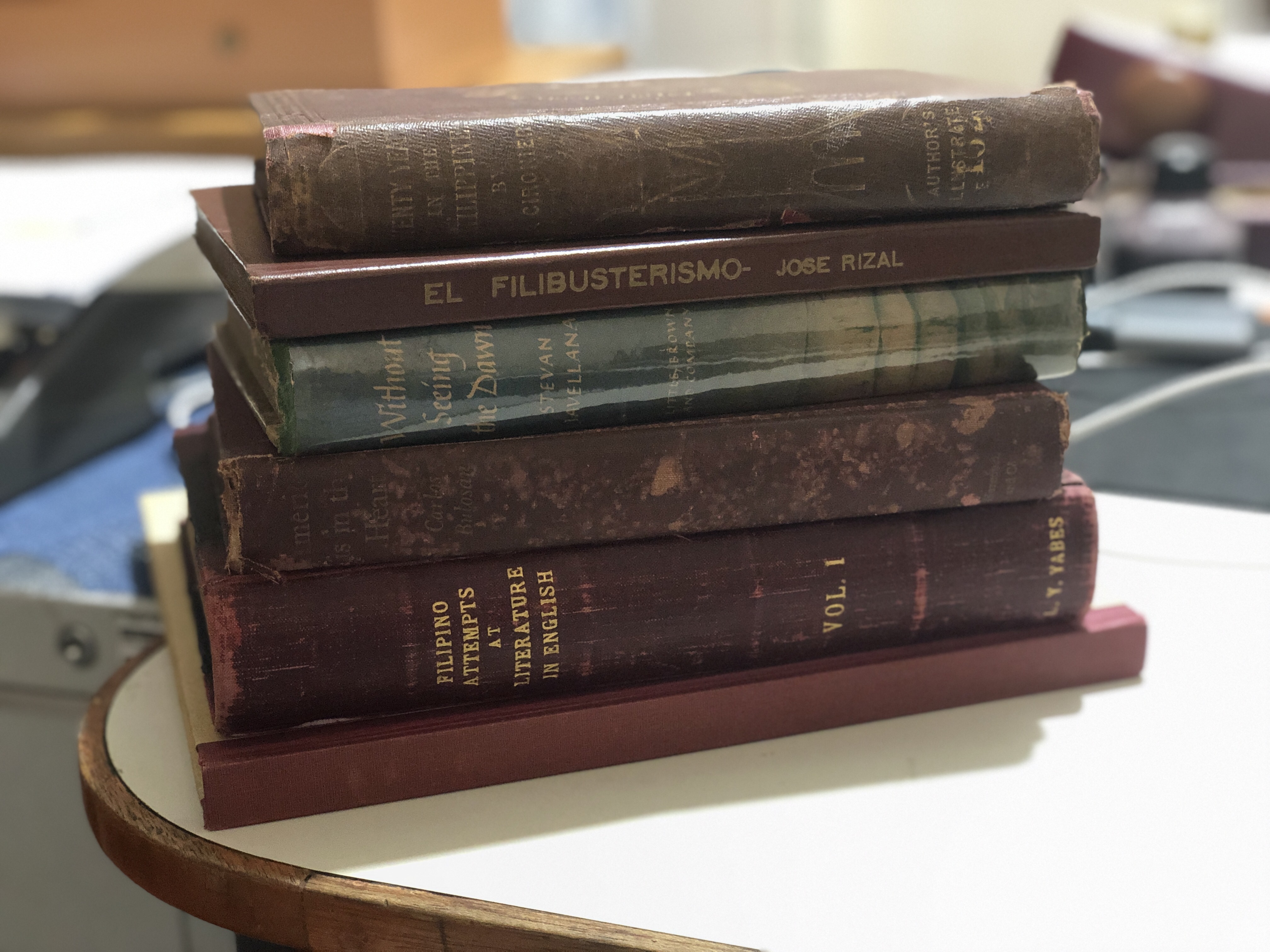

For sheer collecting range and prowess, few can hold a candle to Augusto “Toto” Lozada Toledo, who retired from banking and insurance broking ten years ago. Never mind his 400 fountain pens (older than Toto by a few months, I have about just half that). It would be more accurate to describe Toto as a collector of collections, which comprise, aside from pens, mainly bottles (vintage and modern, soft drinks, medicines, ink, liquor, perfumes, pomades, insulators, Avon figurals, milk and baby bottles, and kitchen glassware) and Batman (action figures, vehicles, Lego sets, and comics).

Ask Toto about the history of Parker Quink (no, not invented by a Filipino as the urban legend has it), and you’ll get a half-hour lecture on Quisumbing Ink and Quesada ink, aside from Quink itself—with all the right props, of course.

A coffee fan, Toto also collects old brewing equipment, coffee cups, used (!) coffee bags, and Starbucks prepaid cards. From his banking and insurance background, he collects old passbooks and checks, vintage fire extinguishers and alarms, metal coin banks, prewar insurance policies, and Zuellig ephemera. (I’m leaving out a lot here, but you get the idea.)

“My main collection is vintage glass bottles—maybe 3,000 specimens—of Philippine products, because of my interest in Philippine history, and how bottles provide clues of their provenance, their makers, their likely users (who actually drank from them), art work (for bottles with paper labels), and the evolution of their logos, which are often tied in to changes in corporate history and ownership,” Toto explains. “The next largest collection is Batman objects—some 2,000 action figures alone. As a seven-year old boy, I read the 1939 issue of Detective Comics No. 27, featuring the debut of Batman, and have always been fascinated by his mental and physical skills that did not originate from alien powers but from his individual training and intellectual prowess.

“The coffee collection comes from a lifelong affair with the brew. The banking and insurance collection comes from a 40-year career in these professions. My first fountain pen was a Wearever Pennant (still with me), that my father gave me as Grade 1 student in 1960. Briefly interrupted by the emergence of Bic ballpens in the 1960’s era, I picked up the collecting in the late 1970s. The others are a result of my interest in the Art Deco aesthetic, my career with the Zuellig Group, my love for Philippine history, and my longing for a return to the mid-century era. It’s always difficult to choose favorite pieces, but for bottles, it would be the Tansan Aerated Water because of the actual etymology of its name, and the (misplaced) brand association with the crown metal cap. The bottle is also very much a part of the American colonial era (strictly recommended for the US military), and was exclusively distributed by F. E. Zuellig, Inc. I also count the San Miguel Beer bottles, from its ceramic containers (from Germany), dark green bottles (from Hong Kong), and the establishment of its own bottle making plant which produced the now-ubiquitous and iconic amber steinies.”

My own most recent acquisitions beyond pens have been, of all things, paper blotters and silver spoons, which began as I idly searched for items Nouveau and Deco. It didn’t help the budget that there are literally hundreds if not thousands of such baubles to be found on eBay at any given time (220,000-plus for fountain pens this very minute). Like Raph, Sandy, Melvin, and Toto, I can spend sleepless nights sighing over some obscure object of desire that might leave wives and mates suspicious, but which they will accept in resignation over more dangerous liaisons.

I’m well aware that there are people who would consider us insane, but let me put it this way: to a world full of ugliness and discord, we bring beauty and order in the cabinets and cases that home and organize our collectibles, and at a time when people forget things after five minutes, we keep the memories of centuries.

Penman for Monday, August 26, 2019

Penman for Monday, August 26, 2019