Qwertyman for Monday, February 10, 2025

I DON’T know why, but like the proverbial bad penny that keeps turning up (English teachers: note the British idiom), every few years, some Filipino school announces its adoption of an “English-only” language policy on its campus, ostensibly in the service of a sublime objective such as “global competitiveness” or “global competence.”

This time around, it’s the Pamantasan ng Cabuyao that’s enforcing the rule. PNC president Librado Dimaunahan has issued a memo declaring that “In line with our vision of developing globally competitive and world class students, the Pamantasan ng Cabuyao (University of Cabuyao) is now an English-speaking campus starting Feb. 03, 2025…. All transactions and engagements with officers, students, employees, and workers should be communicated in English, whether written or otherwise. For strict compliance.” What he wanted to create was no less than “a strong English-speaking environment.”

A few years ago, it was Cavite State University which required its students, teachers and staff to speak exclusively in English or face punishments like getting your ID confiscated and having to sing the CvSU hymn (in English, of course). Filipino could be used only by maintenance workers—and by others, but only in the restrooms and cafeteria.

I’m not going to add to the brickbats that these ideas have already received, not unreasonably. But I will add my two cents’ worth (my, where do these “brickbats” and “two cents” come from?) to the conversation, as a lifelong user and teacher of the language.

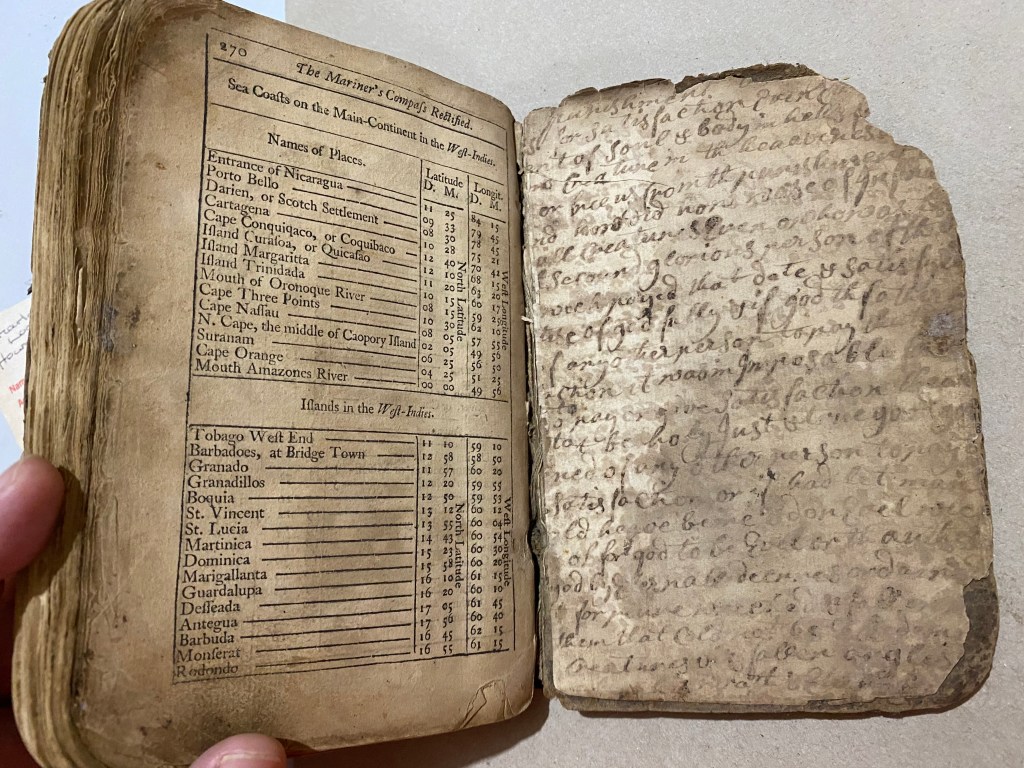

I have a PhD in English—something I don’t often bring up because it sounds so pompous and presumptuous—earned in America where, to my smug satisfaction and my classmates’ consternation, my professor would single out my prose for, among others, its perfect punctuation. I was the only one in our graduate literature class who could explain the difference between parataxis and hypotaxis (no, nothing to do with Yellow Cabs and Uber). Was that global competitiveness? I guess so. Was I proud of my English language skills? Of course. Did it make me or the Philippines any richer? Not a dollar more. Is this what a national language policy should be about? Heck, no.

I’ve done well in English not because I was forced to, but because I love the language, and languages in general. I should have loved Spanish—discovering its beauty too late, when I had to read and translate Federico Garcia Lorca for a grad-school exam—but I didn’t, because we had been forced by our curriculum to take so many units of it (24, in my mother’s time). I started on German and French in high school and college and am picking German up again on Duolingo, in preparation for the forthcoming Frankfurt Book Fair. (I write plays and screenplays in Filipino, despite being born in Romblon.)

What I’ve realized from studying these languages and from a lifetime of writing, speaking, and using English is that in our country of over a hundred languages, English can’t be taught and learned well by exclusively using English. I’m learning German on Duolingo using English.

I don’t mind saying that when I teach creative writing or literature in English, I pause when my students can’t seem to understand what the text is saying—and then we pursue the same line of inquiry in Filipino, and everybody goes “Ah!” It makes simple teaching sense. You can’t get more out of a student—in English—if he or she can’t understand or even recognize the problem, in English.

And just to be clear, these are questions of comprehension and interpretation that even native speakers of English would have a hard time with. (How do I know? I taught the American short story to American undergraduates in Wisconsin.) These are questions like “So what’s John Updike saying about the position of the rebel or nonconformist in society at the end of his story ‘A&P’?” That’s best answerable if you also discuss as we do what America was like in the 1960s, with Vietnam, Woodstock, the civil rights movement, and the moon landing in the background. (I always tell my students that we’re not studying American literature and history to become Americans, but to become better and wiser Filipinos.)

Boomers like me like to recall that in many private schools of our time, students were fined five centavos for every instance they were caught using Filipino. Some may find that quaint or even charming, but if you think anyone learned and loved English because of these stupid rules, think again. Students learn good English from good teachers who don’t teach English as a grammar rulebook but as a road map or even a cheat sheet to an adventure.

English is best learned along the way of learning something else—like how the world works, in science and literature—as a key to unlocking knowledge and meaning. English proficiency all by itself is a non-goal, a false horizon that can delude people into believing that they’ve arrived. Arrived where? What for?

All the English in the world isn’t going to turn the Philippines into an economic powerhouse—which Japan, China, Russia, and Germany managed to become without a mandatory word of English in their curricula from decades back. Better English could make us become more employable as waiters, domestic helpers, and seamen—and I’m not downplaying this, because the language does give us an advantage in those markets—but these jobs, noble as they are, aren’t what universities were made for.

All the English in the world isn’t going to drive a moral spine up the backs of our leaders. Intolerable as it was, one president’s foul mouth and boorish manners may not be far worse than a General Appropriations Act legitimizing the wholesale thievery of people’s money in perfectly edited English.

We can speak all we want with an American accent—only to realize that, in Trump’s America, where one of his appointees has declared pointblank that “It takes a competent white man to get things done right,” the color of your skin still matters more than whether you can pronounce “Adirondack” or “tortoise” correctly. Trump’s maniacal edicts and pronouncements—cutting foreign aid, expelling Palestinians so he can turn Gaza into an American beach resort, and turning the FBI and the DOJ into his personal security force and loyalty police—have all been made in his lazy, slurring English, each word delivering chaos and disaster with as much consequence as Hitler’s Nuremberg rants.

More shameful than lack of proficiency in English is lack of proficiency in one’s own language, which I see in the children of parents anxious to “globalize” their kids without mooring them first in their own culture. Those children will be maimed for life, insulated from and unable to communicate with or relate to their common countrymen. We need our own languages to understand ourselves.

Teach good values and good citizenship. Even if that student’s English turns out less than stellar, our country can’t be worse off.