Qwertyman for Monday, May 5, 2025

TWO WEEKS ago, almost 18,000 young Filipinos and their parents awoke to the good news that they had qualified for admission to the University of the Philippines through the UP College Admission Test (UPCAT). Over 135,000 high school students had applied, so this year’s admission rate stood at just over 13%, almost 7% higher than last year’s outcome.

Whatever UP’s critics may think it’s become, entry into one of its eight constituent universities remains the highest of aspirations for many Filipino families, especially the poor for whom the tuition and cost of living at top private universities is impossible without a scholarship.

UP oldtimers like to recall the days, decades ago, when the quality of public education was still high enough for public and private high school graduates to compete on fairly even terms for admission into UP. It wasn’t unusual for some provinciano wearing chinelas to step into a UP classroom or laboratory and beat the daylights out of some elite-school fellow in academic performance. Many of those provincianos—the likes of Ed Angara, Miriam Defensor, Billy Abueva, and Dodong Nemenzo—went on to stellar careers in government, education, the arts, and industry. UP was clearly doing what it was supposed to do, as its past President Rafael Palma put it: to be “the embodiment of the hopes and aspirations of the people for their cultural and intellectual progress.”

Ironically, by the time the UP Charter was revisited and revised a century after its founding in 2008, giving it the unique status of being the “national university,” UP’s student profile had changed. Jokes about UP Diliman’s parking problems began to underline the popular perception that UP was no longer a school for Filipinos across the archipelago and across income strata but one for the privileged, mainly from the big cities. The introduction of free tuition in state universities and colleges in 2017, while well intentioned, even resulted in subsidizing the children of the rich in UP, who could well have afforded going to Ateneo or La Salle.

But some good news is emerging, as this year’s UPCAT results bear out. Starting with last year’s UPCAT, there’s already been a reversal of the trend favoring graduates from private high schools, with 55% of qualifiers now coming from public and 45% from private high schools. UP President Angelo Jimenez—himself a boy from the boonies, coming out of tribal roots in Bukidnon—has pledged to do even more to give poor students outside of the big cities a better fighting chance of getting into UP.

“We started this banking on two things,” he says, “that UP will respond to the challenge of transforming the so-called common clay—the less-advantaged—into fine porcelain, and that the less-advantaged will respond to the challenge of opportunity. The task of leadership now is to set the enabling environment, structures, and systems to ensure the success of this two-pronged strategy. It’s a big bet, and it gets bigger. We still have the non-UPCAT track. This includes our Associate in Arts program, UPOU’s ODeL, talent-based modes, and finally, the UP Manila School of Health Sciences in Tarlac, Aurora, Palo, and Cotabato. We cannot solve all problems, we are not lowering standards. In fact, we must demand excellence regardless of social and economic status, and enforce it. But we are dropping rope ladders so people long staring up from the base of the fortress walls can have a better chance of scaling its sheer drop with something better than their bare hands.”

Those rope ladders include adding more UPCAT testing centers in faraway places, ultimately to have at least one in each province—a goal that will be met later this year. The testing centers are also being moved from private to public high schools. “We’ve seen that more students tend to participate when the tests are given in their national high schools,” says UP Office of Admissions director Francisco de los Reyes. Aside from more testing centers, UP is helping disadvantaged students prepare better for UPCAT through its Pahinungod volunteers, who distribute reviewers using real items from past UPCATs (these reviewers are also downloadable for UPCAT applicants) and use them for UPCAT simulations, guiding students even with such details as shading the exam oblongs. (De los Reyes reports that wrong shading has caused 20% of their machine counting errors.)

These steps are clearly paying off. Davao de Oro (formerly Compostela Valley), which previously accounted for less than 10 UPCAT qualifiers, has just produced 31, after a testing center was put up in Nabunturan.

UP’s support for poor students doesn’t end with UPCAT. Every year, thousands of qualifiers from so-called Geographically Isolated and Disadvantaged Areas (GIDAs), even after passing UPCAT against all odds, fail to show up for enrollment after realizing that they cannot afford the costs of living on a UP campus. UP has rolled out a P50-million Lingap Iskolar program that provides such disadvantaged qualifiers who meet certain standards P165,000 a year to cover housing, meals, transportation, books, cellphone load, and other expenses. Almost 200 Lingap Iskolar grants were given out last year. In UP Manila, private donors fund daily meals for over 30 students.

I’m particularly happy to report that a dear friend of mine, Julie Hill, recently donated almost P21 million that will be used for a new Agapay Fund that will go toward the upkeep of poor students in UP’s School of Health Sciences, which has a unique ladderized program that enables rural midwives to become nurses, and nurses to become doctors. The program has already produced about 200 doctors who have served their communities back.

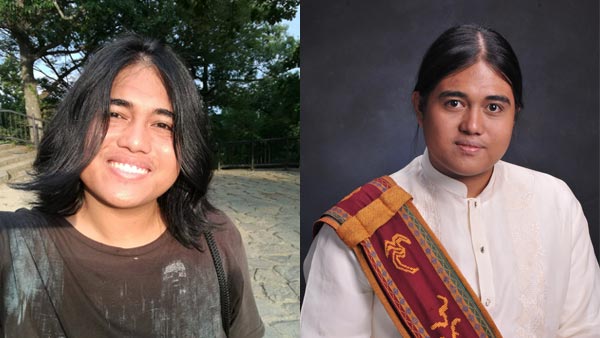

Among them was Dr. Hannah Grace Pugong, who recently landed in the top 10 of the medical board exams, after placing No. 1 in the midwifery and No. 3 in the nursing exams. Dr. Pugong will soon be deployed under the Department of Health’s Doctors to the Barrios (DTTB) program, fulfilling her return service commitment. It is an obligation she willingly embraces, saying that “I have often reminded myself that how I treat my patients should reflect how I want my family members to be treated by other health workers.”

If that’s not what being a national university should be about, I don’t know what is.