Penman for Monday, August 3, 2015

Penman for Monday, August 3, 2015

THE LAST time I thought about Ernest Hemingway, it was a few weeks ago when I was teaching his controversial 1927 short story “Hills Like White Elephants,” one of my all-time favorites for its compactness and subtlety, not to mention its grasp of human psychology.

Coincidentally, when I was giving that lecture, one of the pens in my pocket was an Ernest Hemingway—the first in a series that Montblanc called its Writers Edition pens, issued in 1993. Considered one of the “holy grails” of pen collectors, it had been generously given to me by a fellow member of the Fountain Pen Network-Philippines (www.fpn-p.org); we had a small business arrangement, but the cost of my own service was so negligible that the pen was practically a gift, most thankfully accepted.

My pen’s inscribed with Hemingway’s signature, but ironically, I don’t think Hemingway was ever much of a fountain-pen person, and being the practical, outdoorsy person he was, would probably have disdained carrying anything fancier than a Parker Jotter. He was actually known to favor pencils and typewriters—Angelina Jolie bought his 1926 Underwood as a wedding gift to Brad Pitt—and he wrote this down to explain why:

“When you start to write you get all the kick and the reader gets none. So you might as well use a typewriter because it is much easier and you enjoy it that much more. After you learn to write your whole object is to convey everything, every sensation, sight, feeling, place and emotion to the reader. To do this you have to work over what you write. If you write with a pencil you get three different sights at it to see if the reader is getting what you want him to. First when you read it over; then when it is typed you get another chance to improve it, and again in the proof. Writing it first in pencil gives you one-third more chance to improve it. That is .333 which is a damned good average for a hitter. It also keeps it fluid longer so that you can better it easier.”

I’ve since located an online sample of Hemingway’s handwriting—likely in pencil—which has him drawing up a list of recommended readings for young writers (among them, Stephen Crane’s short stories, Madame Bovary, The Brothers Karamazov, and The Oxford Book of English Verse). It’s comforting to know that his penmanship is a lot like mine—cramped, stiff, and generally ugly.

One of the things that I forgot to mention to my audience—a group of English teachers—was that Hemingway once visited Manila, in February 1941, with the clouds of war already hovering above Europe, where the young Ernest had served as an ambulance driver in World War I. (Ambulance driving seemed to be strangely attractive to young men who would soon make a name for themselves in the arts and letters. Aside from Hemingway, these illustrious WWI volunteers included the writers John Dos Passos, E. E. Cummings, W. Somerset Maugham, and Archibald MacLeish, the composer Maurice Ravel, and the filmmakers Jean Cocteau and Walt Disney.)

In another uncanny connection to fountain pens, Hemingway and Dos Passos served in Italy close to the factory of the Montegrappa fountain pen company, as Montegrappa continues to recall on its website: “Close to the Elmo-Montegrappa factory was situated the Villa Azzalin, which during the conflict. was converted into a field hospital. Two volunteer ambulance drivers for the Italian Red Cross at that time were the famous writers Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, both of whom spent many happy hours visiting the factory and experimenting and testing various Montegrappa fountain pens, and availing themselves of the Company’s after-sales service.”

But back to Hemingway in Manila.

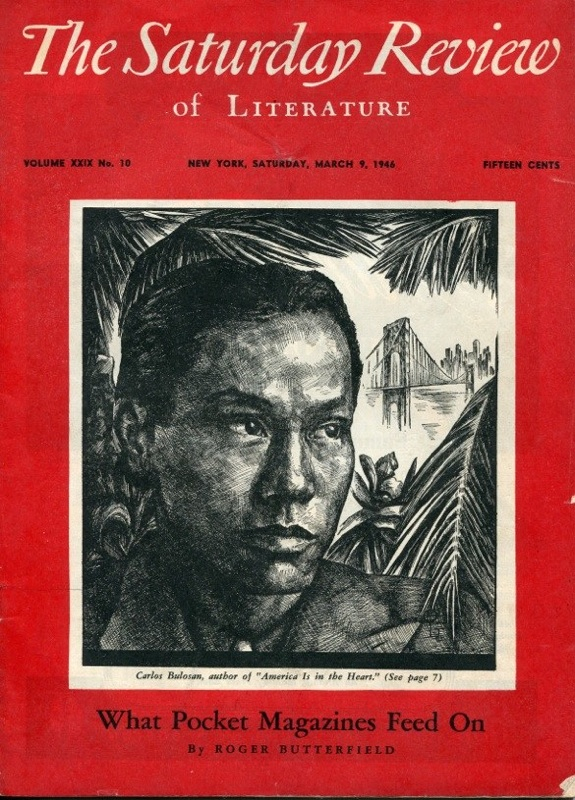

An article by Brown University Prof. George Monteiro in The Hemingway Review (Fall 2010) talks about Hemingway’s short 1941 visit, a stopover on his longer assignment to China as a journalist. Accompanying Hemingway then was his third wife Martha Gellhorn, herself a distinguished writer, a novelist and a war correspondent. (Annoyed by her frequent absences—she would be the only woman to land with the Allied troops on D-Day—Ernest wrote her to ask, “Are you a war correspondent, or wife in my bed?” She led a long and colorful life after her divorce from Hemingway, and tragically, like Ernest, died by her own hand at the age of 89 in 1998.)

Flying to Hong Kong by Pan Am Clipper from San Francisco via Honolulu and Guam, Ernest and Martha stopped by in Manila for a few days and stayed at the Manila Hotel, and managed to meet with representatives of the Philippine Writers League, which was then led by Federico Mangahas. There’s a picture in the Flickr photo gallery maintained by Malacañang’s Presidential Museum and Library (whose Director, Edgar Ryan Faustino, just happens to be a member of FPN-P), taken from A.V.H. Hartendorp’s Philippine Magazine, showing Hemingway meeting with Filipino writers.

Seeing it reminded me of a similar picture of the big white Ernest looming over a small brown young Filipino named Nestor—a picture that NVM Gonzalez himself showed me in the 1990s, which sadly may have been lost in the fire that later razed the Gonzalez home in Diliman. Monteiro’s account mentions that Hemingway shared this bit of wisdom with his Filipino counterparts: “I think a writer’s gravest problem, always, is to write the truth and still eat regularly.”

Unfortunately I couldn’t access the rest of the Monteiro article online (you need membership access to Project MUSE), but I read enough of it to understand that brief as it was, Hemingway’s stopover created quite an impact, enough for the Manila Hotel to use a quote from the big guy as one of its taglines: “If the story’s any good, it’s like Manila Hotel.” The bayside hotel, founded in 1912, has of course hosted other luminaries such as Douglas MacArthur, John Wayne, John F. Kennedy, and the Beatles, aside from another popular postwar writer, James Michener.

As we all know, Hemingway killed himself with his favorite shotgun in July 1961, seven years after receiving the Nobel Prize for literature, in a fit of depression. It was a sad ending to a many-splendored life that we were privileged to glimpse, however briefly.

Penman for Monday, July 29, 2013

Penman for Monday, July 29, 2013