Qwertyman for Monday, November 10, 2025

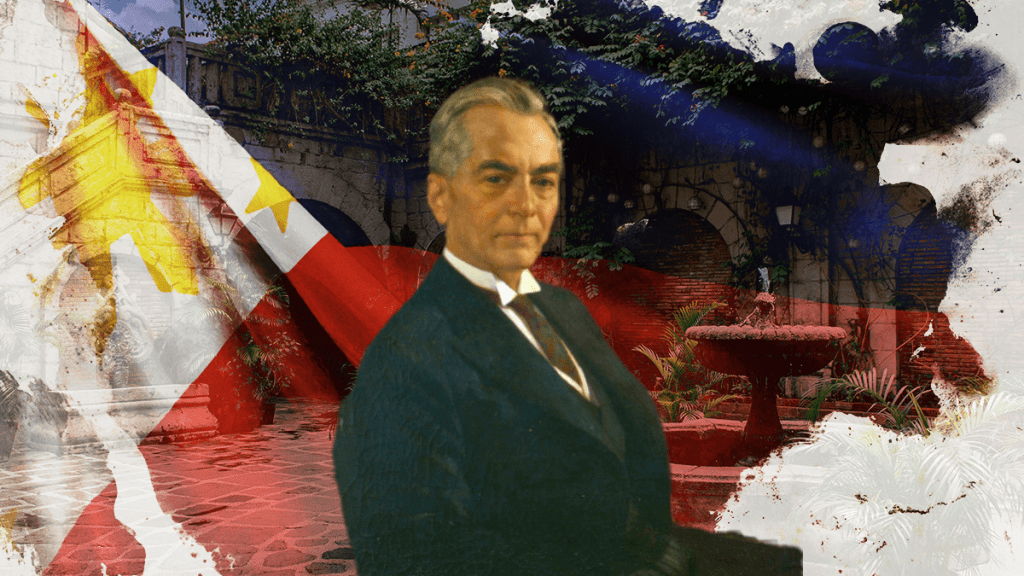

I’M COMING late to the party, having been away for a couple of weeks, but even in faraway Frankfurt, I was itching to come home to see what the brouhaha over the “Quezon” movie was all about.

Rarely does a Pinoy movie stir a hornet’s nest like this one did, and even without seeing it, I took that as a good sign for our film industry, especially big-ticket projects which sometimes leave people wondering why they were even made.

What especially piqued my interest, of course, was the reaction of Quezon family members and friends who thought the old man’s cartoonish depiction as a womanizing, scheming, and power-hungry politician despicable.

Now, my own grandfathers led pretty quiet lives, so I’m sure that if anyone called them womanizing, scheming, and power-hungry, I’d be mighty upset, too.

The difference is, unlike my lolos and going by what the historians suggest, Manuel Luis Quezon seems to have been all of the above—which isn’t to say he wasn’t much more than all those negatives put together. It was apparently that “much more” that the Quezonistas were looking for—MLQ the patriot and freedom fighter—to balance out the picture, especially since most young Filipinos know nothing of the man except as a place-name. Had that been shown, the outrage might arguably have been muted, the image softened.

But of course that wasn’t what the movie’s makers were going for. As has already been noted by dozens of reviewers before me, “Quezon” is no documentary (and let’s not forget that even documentaries can be biased—just watch Leni Riefenstahl’s adoring portrayal of Hitler and his Nazis in her bizarrely beautiful “Triumph of the Will”). From the outset, it declares that it is mixing up history with “elements of fiction,” which is just as good as using that old commercial come-on, “based on a true story.”

I’m no historian—I’ll confess to being an enthusiast—but as it so happens, I’ve been a playwright, screenwriter, biographer, and fictionist at various points of my otherwise uneventful life, so I can probably speak to these issues with some experience. I can attest, for example, having written some biographies of the rich and famous, that families and descendants can inherit myths about their patriarchs, and treat and pr0pagate them as God’s own truth.

My take is, I don’t think we should receive “Quezon” as history, biography, fiction, or even film. It’s theater (captured on film), and it declares itself as such right from the beginning, as I’ll shortly explain. This may be due to the fact that the script was co-written by one or our most accomplished playwrights, Rody Vera, alongside director Jerrold Tarog. His approach was explicitly stylized and non-realistic, from the use of silent-movie title cards, ghoulish makeup, and painted backdrops in the black-and-white sequences (including that almost balletic choreography of the young MLQ rising from the floor of his prison cell) to the conception and blocking of such scenes as those of Quezon working the floor of the House and the capitalist bosses gathering round the table. (If all this seems obvious and elementary, dear reader, my apologies—in these days of TikTok, I don’t know what people are looking at anymore).

So what if the movie is theater disguised as film? Does that explain or excuse its supposed excesses and exaggerations?

Well, theater is, almost by nature, exaggeration—movements and motives get simplified and magnified, the easier to get them across. Theater is agitational—it aims to provoke emotion, to bring people to their feet, clapping in delight or screaming in rage.

And that’s what “Quezon” did, didn’t it? It got its message across, effectively and efficiently, like a train on schedule, and taking it as theater, I found it roundly entertaining. By and large, the actors carried themselves off with aplomb, from Jericho Rosales’ masterful Quezon, Romnick Sarmenta’s comic-cool Osmeña (his was actually the most difficult role to play, to my mind), Mon Confiado’s aggrieved Aguinaldo, and Karylle’s restrained Aurora. The employment of the fictional journalist Joven Hernando was what a smart scriptwriter would do, to weave the narrative threads together. (Teaser: Quezon and Aguinaldo figure in the novel I’ve been writing about prewar Manila.)

My quibbles have to do with minor complaints like (don’t be surprised) “Wrong period fountain pens again, all of them—why don’t they ever ask me?” (Quezon did hold his pen that odd way, though) and “Does every movie chess scene have to end with a checkmate?” I could have added “Why does everyone’s shirt and pants look fresh in a period movie?” but we’ll excuse those as theatrical costumes.

If there was anything I would have added to the content, it would have been a quiet moment of self-reflection, in which we realize just how Quezon sees himself. That alone might have lifted up his character from caricature.

The real Quezon seems to have been every bit as petty as the movie shows him to be, but also every bit as great, as it seems to have taken for granted.

Quezon had something of a history with the University of the Philippines, whose protesting students (one of them a young buck named Ferdinand Marcos, who accused Quezon of “frivolity” over all the dance parties in Malacañang) led him to ride into UP’s Padre Faura campus astride a white horse to either charm or intimidate them.

He had a long-running tiff with then UP President Rafael Palma over the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act, and when Palma retired after ten hard years in the hot seat, citing a technicality, the government denied Palma the gratuity that was his due. When Palma died, however, Quezon reportedly went to his wake to deliver a eulogy worthy of the man.

You didn’t see that Quezon in the movie—and then again, maybe you did.

(Image from banknoteworld.com)