Penman for Monday, January 28, 2019

THE RECENT return of the fabled bells of Balangiga from the American West to their home in Samar reminded me of my fleeting involvement years ago in the effort to draw renewed attention to that traumatic episode of the Philippine-American War.

Sometime in 2001, the late film director Gil Portes called to ask me to work with him on a project that would focus on what people—echoing the American view—were then calling the “Balangiga massacre,” culminating of course in the loss of the bells (hardly the event’s most tragic outcome, considering the slaughter of innocents that the Americans undertook in the attack’s aftermath).

I suppose we were still basking in the afterglow of the Philippine Centennial, and directors were eager to take on historical subjects, long before Heneral Luna would prove that history artfully told could do well at the box office. In fact, our project ran alongside a similar one being put together by the formidable tandem of director Chito Roño and screenwriter Pete Lacaba. (Pete and I were good friends and knew what the other was doing.) The main difference was that our version was going to be a Filipino-American co-production, with the script in English, for a global audience.

I can’t recall now who our producer was, but I knew that Gil was in conversation with US-based financiers, and I did get a down payment for the sequence treatment and the script itself, so we were seriously engaged in the project—seriously enough that Gil and I went on a reconnaissance visit to Balangiga.

Balangiga is a small fourth-class municipality in Eastern Samar, reachable by surprisingly good roads (at least that long ago) from Tacloban across the San Juanico Bridge and past Basey. When we went there, we were billeted in the only “hotel” in town, where the rooms cost P100 a night and I tried to read my notes under a 10-watt lamp. But we were able to find and interview the descendants of Valeriano “Bale” Abanador, the town’s chief of police who led the attack in retaliation against American repression. I was even shown the wooden stick that Abanador was supposed to have waved as a signal to begin the attack that morning of September 28, 1901.

Sadly, after all the research and three drafts of the script, and despite rumors that Sony was going to be involved and that the likes of John Malkovich were being considered for the lead roles, our project fell through, as did the other one. One reason I heard was that in the wake of 9/11, it was proving difficult to bring a battalion of American actors over. Years later, Gil asked me for a copy of the script, thinking to revive the project, but then Gil himself died suddenly two years ago.

I don’t pretend to be a Balangiga expert, although I drew heavily on the writings of such real Balangiga scholars as UP Prof. Rolando Borrinaga and writer Bob Couttie, who have sorted much of the fiction from the facts of the event. I did fictionalize my treatment, as I was expected to do for dramatic purposes, without altering the basic facts as they were known to me. My chief conceit was to create a character named Ramon Candilosas, the fictional son of the bell ringer Vicente, who was a teenager when the attack happened.

My treatment opened this way:

SEQ. 1. Intro. EXT/INT. Fort Warren, Wyoming. Day.

An old man, around 70, walks across the yard in Fort Warren, Wyoming, to where they keep the Balangiga bells. He pauses before one of them, takes off his hat, and reaches out with a trembling hand to touch one of the bells.

Later, we see him signing his name with a scratchy fountain pen on a guestbook; a CLOSE-UP reveals his name: RAMON CANDILOSAS. “I do not know everything,” his voice begins to intone. “This is only what my father told me, and what I imagine to have happened in our hometown, in a war over a hundred years ago. It is a war we have forgotten, a war we find difficult if not impossible to believe.”

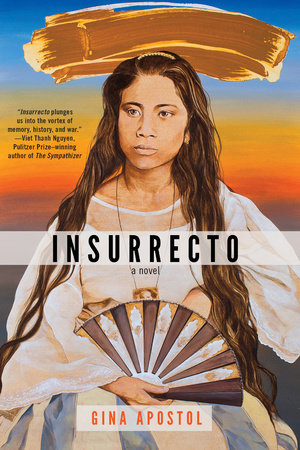

Indeed, as I often remark to my American friends, I can understand if few Americans remember the Philippine-American War (downplayed for the longest time in American annals as the Philippine Insurrection). What’s sad is how few Filipinos do. At least writers like the US-based Gina Apostol are reviving that memory through her most recent and highly acclaimed novel Insurrecto, a complex and contemporary take on that century-old event.

But I’m glad for history’s sake that the bells are back, and that, for once, the fact has overtaken the fiction.

Penman for Monday, December 24, 2018

Penman for Monday, December 24, 2018

Penman for Monday, December 10, 2018

Penman for Monday, December 10, 2018

Penman for Monday, November 5, 2018

Penman for Monday, November 5, 2018