Penman for Sunday, April 6, 2025

FEW MAY have noticed, but this year, 2025, marks the centenary of what has been widely acknowledged to be our first classic short story in English, Paz Marquez Benitez’s deathless “Dead Stars.”

As I’ve often observed as both a writer and teacher of Philippine literature, there’s probably no literary form more popular among Filipinos than the short story and its predecessors—myths, legends, folktales, and such stories that draw on the power of narrative to tell and teach us something about human life.

A lot of this has to do with the fact that people and cultures everywhere have made use of stories to make sense of things—to establish causality in human actions—often as a way of prescribing and also proscribing certain behaviors. Stories were there to learn from, like the biblical parables, Aesop’s fables, and the creation myths. The more exciting and entertaining the stories were, the easier the learning happened. Even the mere recognition of oneself in a story that could have taken place a thousand years ago in a place across the planet makes our lives seem more meaningful.

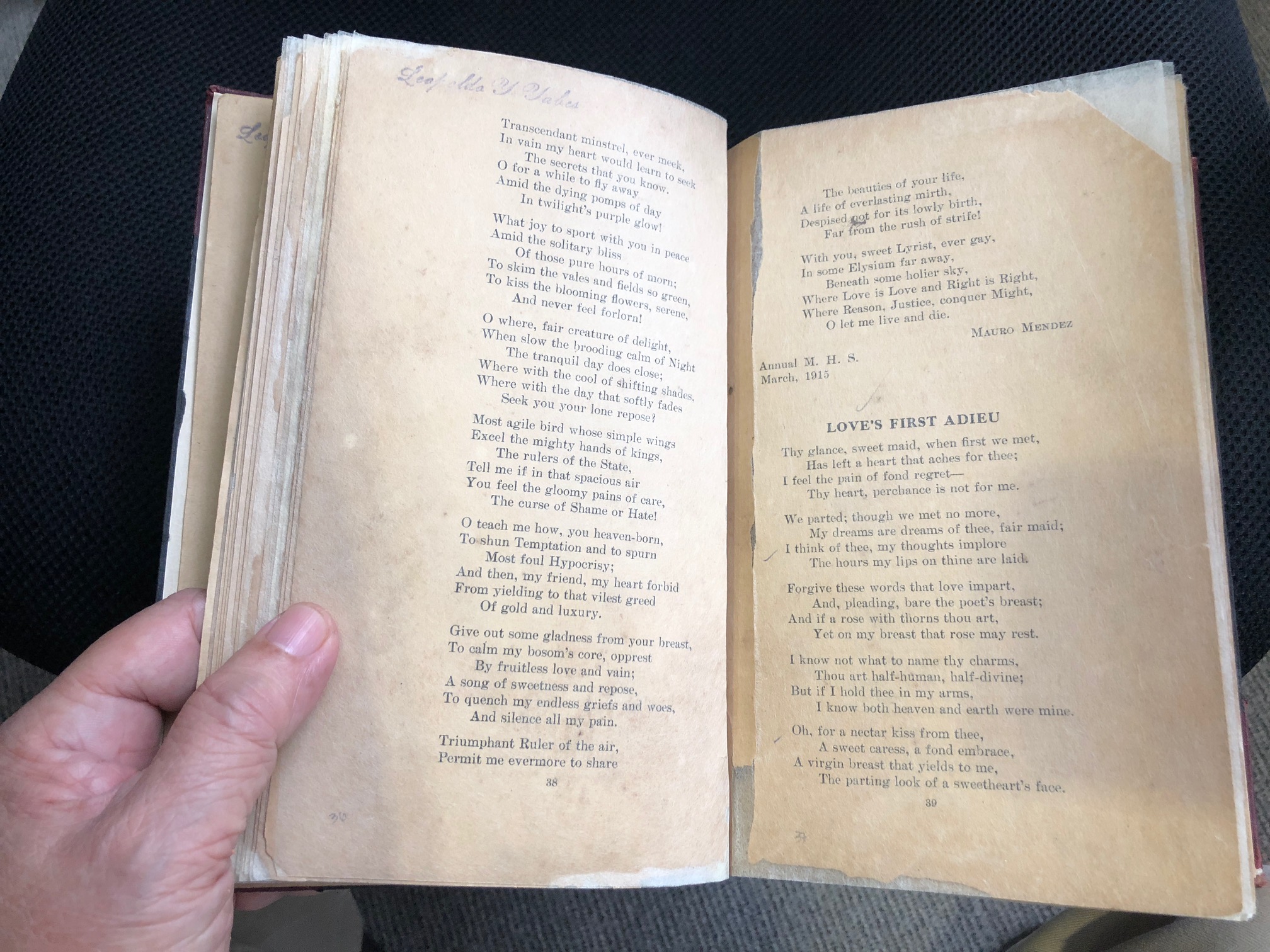

In the Philippines—as it did in the West, where the modern short story took form—the short story was a staple of prewar weekly magazines like the Sunday Tribune, where a story written by an American author would be matched by a local story during what our early literary scholars like Leopoldo Yabes would call our period of apprenticeship. This was in English, but the short story in Filipino (then Tagalog) and other Philippine languages had developed even earlier, and continued (as it continues) to explore new forms and material.

Why the short story and not the novel? That’s another long discussion to be had, and I’ve addressed it in a lecture titled “Novelists in Progress,” but the short of it is that, well, we Pinoys like things in small doses (think Nick Joaquin’s “heritage of smallness”), and the short story satisfies our craving for a touch of fiction and fantasy in our ordinary lives. We’re not marathoners, but great sprinters; we’re not summiteers or navel-gazers, but masters of the street and alley.

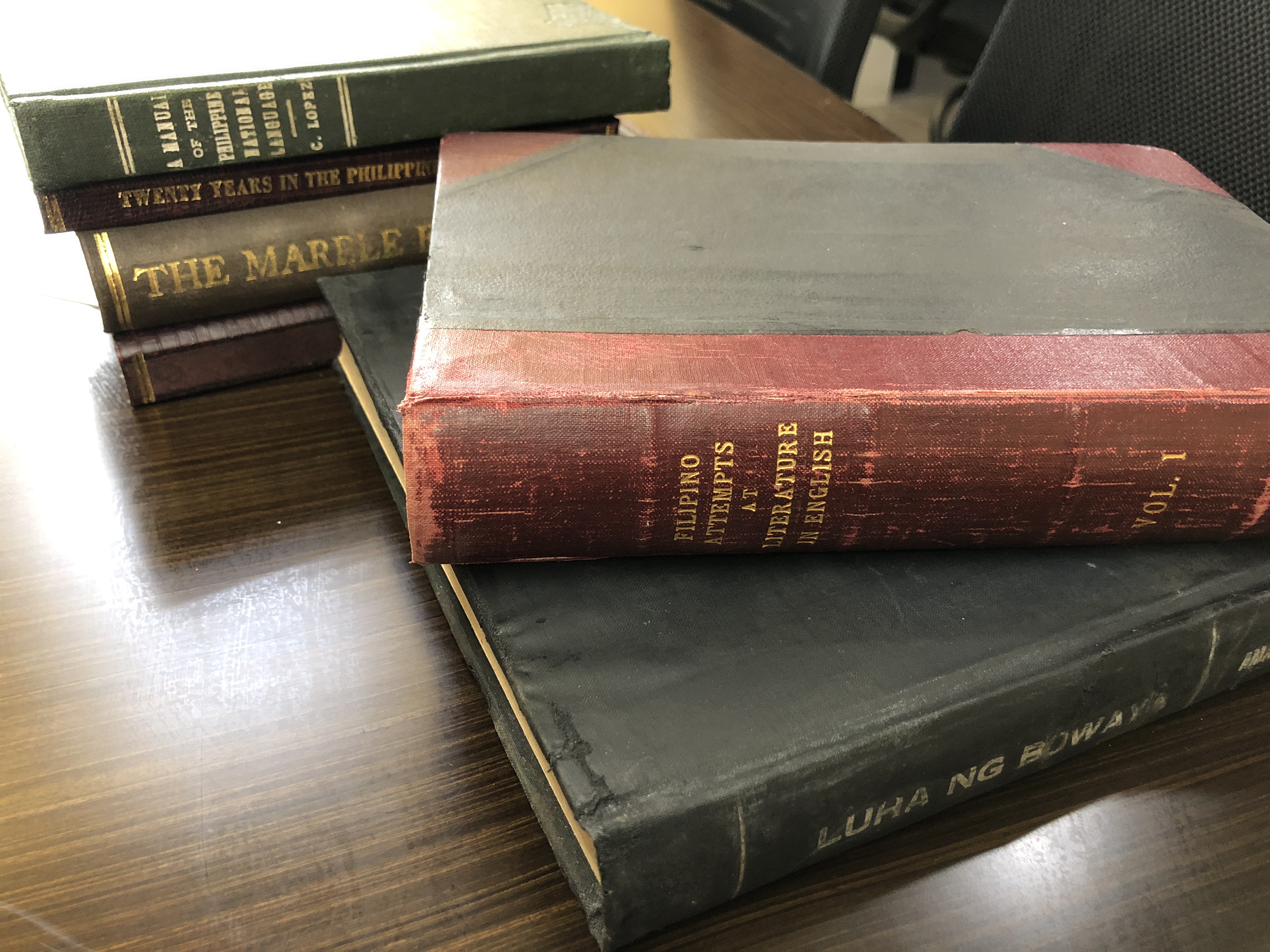

And so, over the past century, important anthologies of the Philippine short story have been published, tracking the development of the genre and its practitioners, from Yabes’ landmark Philippine Short Stories 1925-1940 (a project continued by Gemino Abad for 1956-2008) to Isagani Cruz’s Best Philippine Short Stories of the Twentieth Century (2000). Outside of English, Mga Agos sa Disyerto edited by Efren Abueg came out in 1964, proclaiming new directions for Tagalog short fiction, and the much-needed Ulirat: Best Contemporary Stories in Translation from the Philippines was published in 2021, edited by Kristine Ong Muslim.

But the 21st century is now a quarter of the way through, and just in these past two decades or so, a fresh bumper crop of brilliant new stories has built up, awaiting harvest.

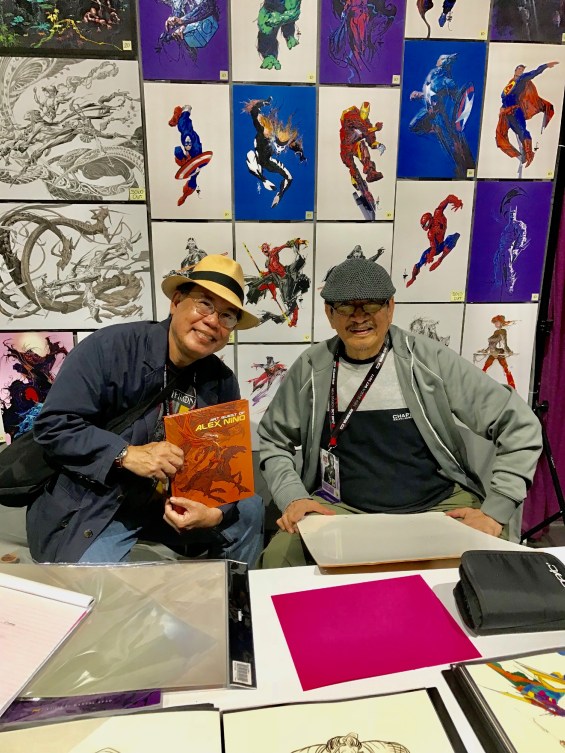

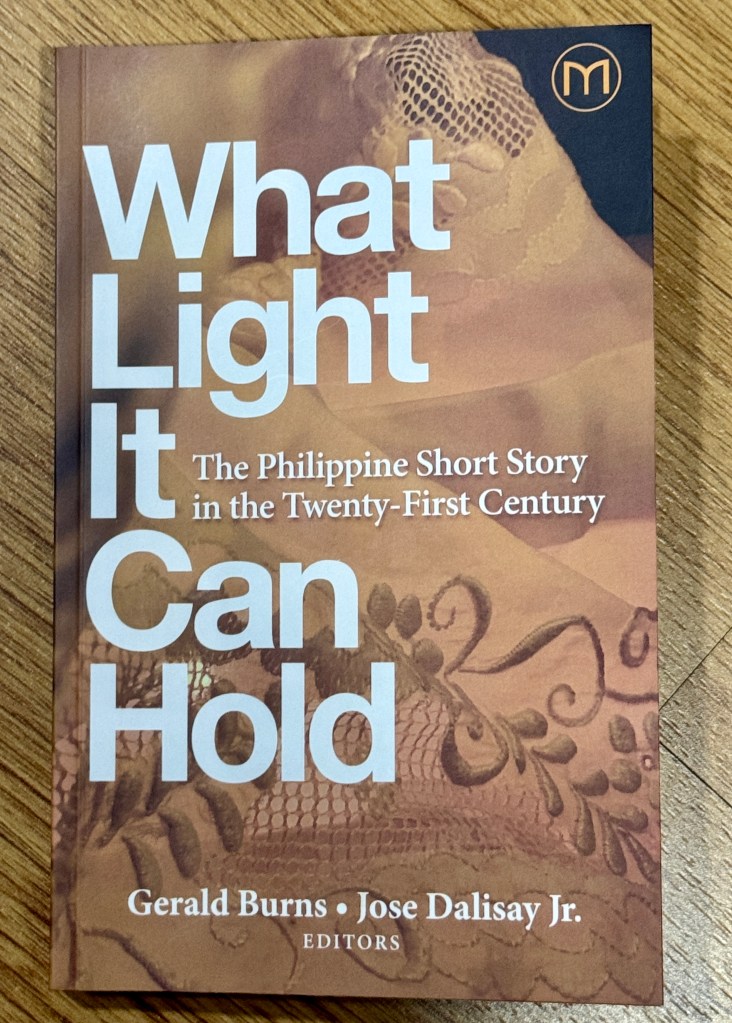

Five years ago, an American friend named Gerald “Jerry” Burns—a fellow academic and a scholar of Philippine literature in English, now Emeritus Professor at Franklin Pierce University in New Hampshire—decided to do just that: review the best of the newest Philippine short stories and produce a selection with which to introduce them to the world. He needed a collaborator, and having worked with Jerry earlier when he was a Fulbright professor at our English department in UP, I agreed to co-edit the volume with him. Because of our backgrounds, our stories would be mainly those written in English (and the excellent Ulirat had already covered much more ground in the other Philippine languages than we ever could) but Jerry wisely insisted that we should have at least some representation of non-English stories in translation in the book, if only to lead the reader to explore more in Ulirat.

The selection process was predictably long and bruising, with all the political, aesthetic, and practical considerations that go into anthologizing, but in the end we came up with 18 stories written by both familiar and fresh names, from within and beyond the Philippines, including the diaspora: Dennis Andrew Aguinaldo, Dean Francis Alfar, Mia Alvar, John Bengan, Ian Rosales Casocot, Richard Giye, Vicente Groyon, Ino Habana, Carljoe Javier, Monica Macansantos, Perry Mangilaya, Doms Pagliawan, Ma. Elena Paulma, John Pucay, Anna Sanchez, Larissa Mae R. Suarez, Lysley A. Tenorio, and Socorro Villanueva. We also found an agreeable and supportive publisher, Milflores Publishing, fortuitously run by Andrea Pasion-Flores, herself a fine fictionist who understood the need for a new anthology like this, especially on the threshold of the Philippines’ participation as Guest of Honor in this year’s Frankfurt Buchmesse.

The book’s title, What Light It Can Hold: The Philippine Short Story in the Twenty-First Century, was suggested to Jerry by an encounter with the piña weavers of Kalibo, Aklan, and a caption he saw that said: “How fragile a single thread of piña is, how delicate, but look how much light it can hold.” He explains that “What Light… is intended to recognize the limited capacity of the Philippine short story in this period to offer any widespread or definitive illumination of the nation’s life and culture. At the same time, a more expansive understanding of that title is possible. For the short story, as will be suggested in the next pages, is a signature Philippine product, too. And these slender narratives, fashioned by their makers with a skill, patience, and devotion comparable to the piña weavers’, bring what light they can hold to vital areas of contemporary Philippine and larger human experience.”

No anthology project will be without its perceived failures and omissions, and Dr. Burns and I remain fully open to criticism in that respect. But we believe the sympathetic reader still stands to profit from both the selections and the introduction, penned largely by Jerry, that makes salient observations on the changes that have taken place in this most favored literary form of ours over the past century. Happy reading! (What Light It Can Hold is available on Lazada and Shopee.)

Penman for Monday, December 24, 2018

Penman for Monday, December 24, 2018