Penman for Sunday, April 7, 2024

WHY IS it that just when you think you’ve begun to figure out a foreign city’s transport system, it’s time to come home? That happened again barely two weeks ago when my wife Beng and I flew to France for some speaking engagements in Paris and Le Havre. We were there for work, not tourism, and more work waited for us as well back home, so we couldn’t stay for as long as we would have wanted to. We’d been to Paris three times before and had done the obligatory Louvre and Eiffel Tower visits, but it almost seems criminal not to linger and loiter around such a beautiful city.

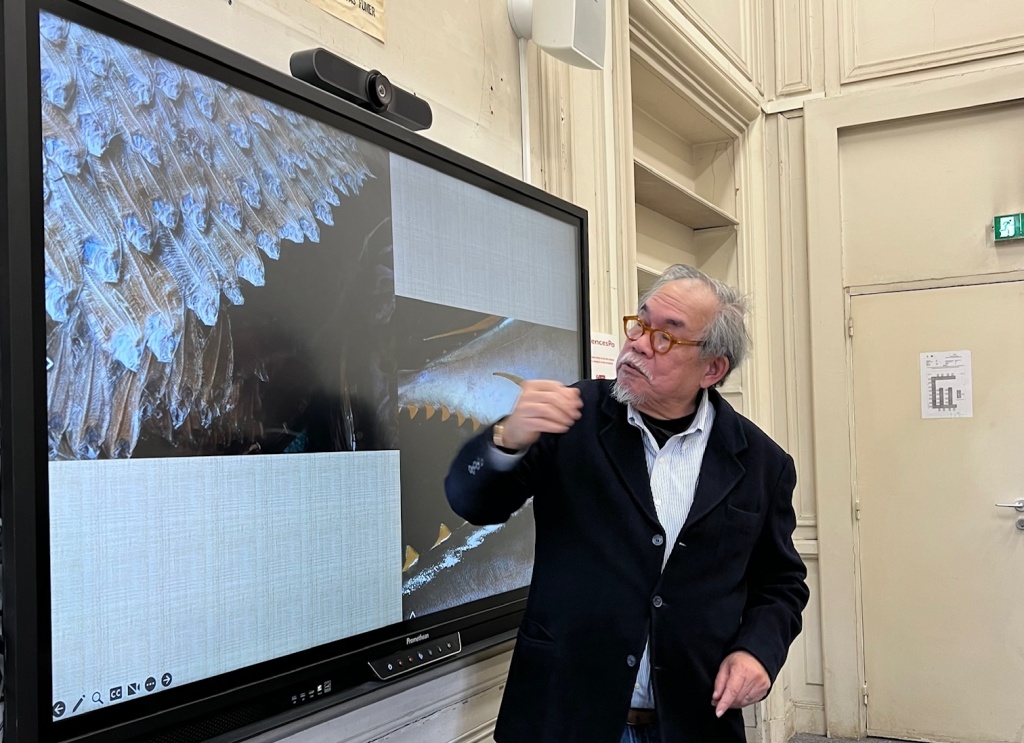

We were there at the invitation of SciencesPo, France’s leading social sciences university, for a series of talks on Philippine literature and art. Along with France-based writer Criselda Yabes, I gave a reading as well at the Philippine embassy in Paris at the behest of our most gracious ambassador, Mme. Junever “Jones” Mahilum-West, an avid amateur painter and supporter of Philippine culture. Our host at SciencesPo, Dr. Pauline Couteau, also arranged some events for us at their campus in Le Havre and sponsored a special screening of Lino Brocka’s classic “Maynila sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag” at the Entrepot Theater in Paris.

It was a hectic week that left these footloose septuagenarians exhausted but exhilarated at the same time, warmed up in France’s unseasonably chilly weather (often falling below 10C) by the enthusiasm of our new friends, both French and fellow Filipinos.

Again, however, we had a sweet problem to deal with even before we flew to Paris: with such little time left on our schedule for more casual diversions, what places or experiences would we put on top of our list for our relaxation and amusement, given Paris’ almost inexhaustible offerings of wonder and delight?

Anthony Bourdain, bless his soul, famously advised short-term visitors to Paris not to make a mad dash to try and see everything all at once, but to just relax, have coffee, imbibe the neighborhood culture, stay in bed (and for those able and inclined, make love). Beng and I recalled, with both fondness and regret, how we had first seen Paris a quarter-century earlier from the back of a bus on a 99-pound budget tour from our base then in Norwich, England. The bus went by the city’s landmarks so fast that Beng missed Rodin because she was in the on-board restroom then. Subsequent visits afforded us a bit more time to see the Mona Lisa (of course) and to go up the Eiffel Tower (of course) but our happiest memories came, as Bourdain suggested, from just walking in the city gardens and along the Seine.

This time, we decided to do just two things with our limited free time: visit one museum, and hit the flea markets. This follows a pattern that Beng and I have observed over decades of traveling together, from Amsterdam, Barcelona, and London to New York, Tokyo, and Shanghai. The museums capture and preserve the glory of the past, and if you’re lucky, rather than pay for made-in-China miniatures at the museum gift shop, you can find some genuine article from that past in the flea market.

Our choice of museum was easy: Paris has dozens of fantastic museums—and you’ll never, ever finish the entire Louvre in one visit—but the great one we’d never been to was the Musée d’Orsay, the former train station that’s become France’s cathedral of Impressionism. Finally, this time, in the few hours we had just before boarding the train to Le Havre, we managed to step into the Musée d’Orsay, and what a divine experience e that was, to find room after room filled by the masterworks of Renoir, Monet, Manet, Seurat, Degas, Redon, Courbet, and so on, like walking into a book of pictures.

Understandably, hundreds of other people had the same idea, so the best time to visit may have been after 6 pm—the museum closes at 9:45—when admission rates are also cheaper. Not a few friends have remarked that they found the Musée d’Orsay much better than the Louvre, perhaps because of its relative compactness and its delivery of proven crowd-pleasers in its collection.

Our flea-market sorties proved just as wondrous, with the additional thrill of unpredictability, as each table will be different from the one before it and you need a quick, trained eye to spot the jewel in the junkyard. As flea-market addicts from decades back when we used to scour the yard sales and antique barns of the American Midwest for things we could drag home, Beng and I have developed a routine of scan-and-scrutinize, looking for our respective grails (old fountain pens for me, old bottles and costume jewelry for her).

We were lucky to be billeted near our first flea market, the one at Porte de Vanves, which has about a hundred dealers strung along a large city block selling all manner of goodies from 18th-century books and Christofle silverware to walking sticks and paintings. I searched in vain for that lost Juan Luna and that stray copy of the Fili (which Rizal finished in Paris), but the flea-market gods blessed me instead with an early 1900s “safety” fountain pen sheathed in gold, perfect in every way, lying all by its lonesome on a table of bric-a-brac. “Combien, madame?” I asked in my schoolboy French, my throat dry with anticipation. “Cinquante euros,” she said; it was easily worth five times that, but I gathered up all my courage and countered, “Quarante?” “Okay,” she said, “A quick “Merci!” and 40 euros later, I was a happy boy with a new toy—what could be a better memento of this short trip than a gorgeous century-old pen with the word “Paris” on its 18-carat nib?

Of course, this luck was not to be repeated on our visit to the big flea market of St. Ouen in Clignancourt—reputedly the largest of its kind in the world—a few hours before boarding the plane back for home, but we rewarded our labors with a late lunch in a Chinese restaurant. After a week of French cuisine, immersed in the grandeur of French art and culture, huge platefuls of Cantonese fried rice sounded just about right. It was as if we were being told, “You’ve had your Parisian interlude and your souvenirs, it’s time to go home.” Au revoir!