Hindsight for Monday, April 11, 2022

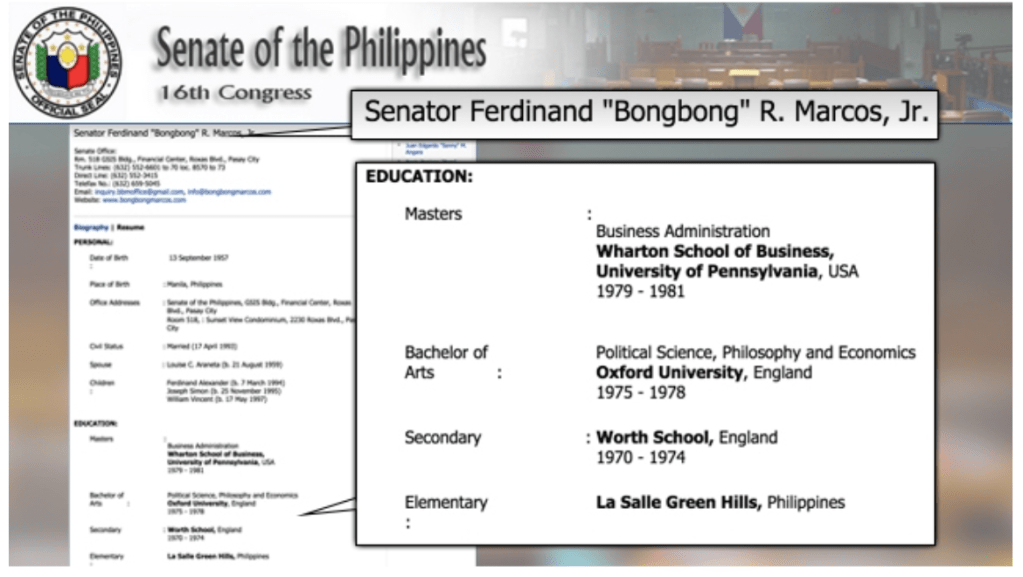

I’VE RECENTLY come across a number of posts online by people complaining about the “self-righteousness” of campaigners for a certain candidate to explain why they might, or will, vote for the other guy—yep, the tax evader, debate dodger, academic cipher, political under-performer, and, if the surveys are to be believed, our next President.

Now, I can understand their irritation. Nobody likes to be told they’re wrong to their faces, or have the truth shoved down their throats.

I can just hear someone muttering: “How can you be so sure of your manok? Don’t you know she’s an airhead, lost in space, a Bar flunker, an unwitting decoy for the (choose your color—Reds or Yellows)? There may not be much I can say for my bet—and okay, I’ll admit I don’t really know or care what he thinks because he’s not telling—but I prefer him to your insufferable assumption that you and your 137,000 friends are torchbearers for the good, the right, and the just. (And you’re such a hypocrite, because I know what you pay your maids, which isn’t more than what I pay mine, but at least I don’t pretend to be some crusading reformer.) To be honest, it’s you I can’t stand, not since you put on that silly all-pink wardrobe and plastered your gate and walls with pink posters. But guess what—you’ll lose! All the polls say so, and I can’t wait to see you crying your eyes out on May 10.”

Whichever side of the political fence you’re on, I’ll bet my favorite socks (which I haven’t worn for the past two years) that you know someone on the other side who’s thought of or verbalized what I just wrote. The forthcoming election has become a test not just of friendships, but of how far some of us are willing to pretend that all politicians are the same, all opinions are equal and should be equally respected, XXX number of people can’t be wrong, and that whoever wins, democracy will, as well.

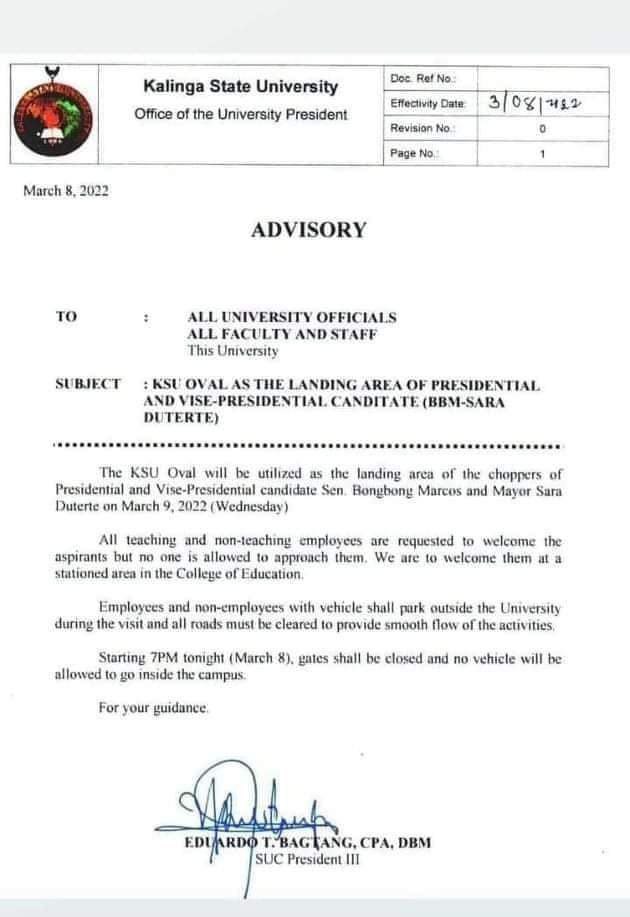

This presumes a parity of political, financial, and moral power that just doesn’t exist and probably never did, at least in this country. The playing field is far from even. It’s been horribly distorted by disinformation, vote-buying, intimidation, and who else knows what can happen between now and May 9 (and the days of the vote count, after). The dizzying game of musical chairs that preceded the final submission of candidacies to the Comelec last October (resulting, ridiculously, in the ruling party being frozen out of serious contention for the top two slots) was but a preview of the seeming unpredictability of Elections Ver. 2022. I say “seeming” because there may be outfits like the former Cambridge Analytica that will presume to be able to game everything out and bring a method to the madness that will ensure victory for their clients.

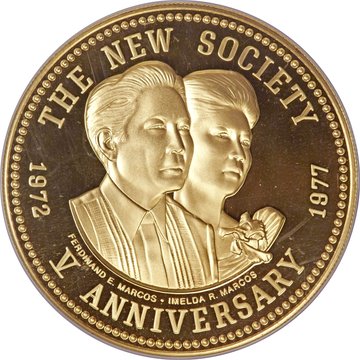

What we know is that this will be the first presidential election, at least in recent memory, where the presumptive frontrunner refuses to be questioned about important issues, faces legal liabilities that would crush anyone less powerful, campaigns on little more than a vapid slogan, ignores China’s encroachment into Philippine territory, claims to know next to nothing about his parents’ excesses, and takes no responsibility for them. Even more alarmingly, his lead in the polls suggests that these issues don’t matter to many voters, thanks to miseducation and disinformation.

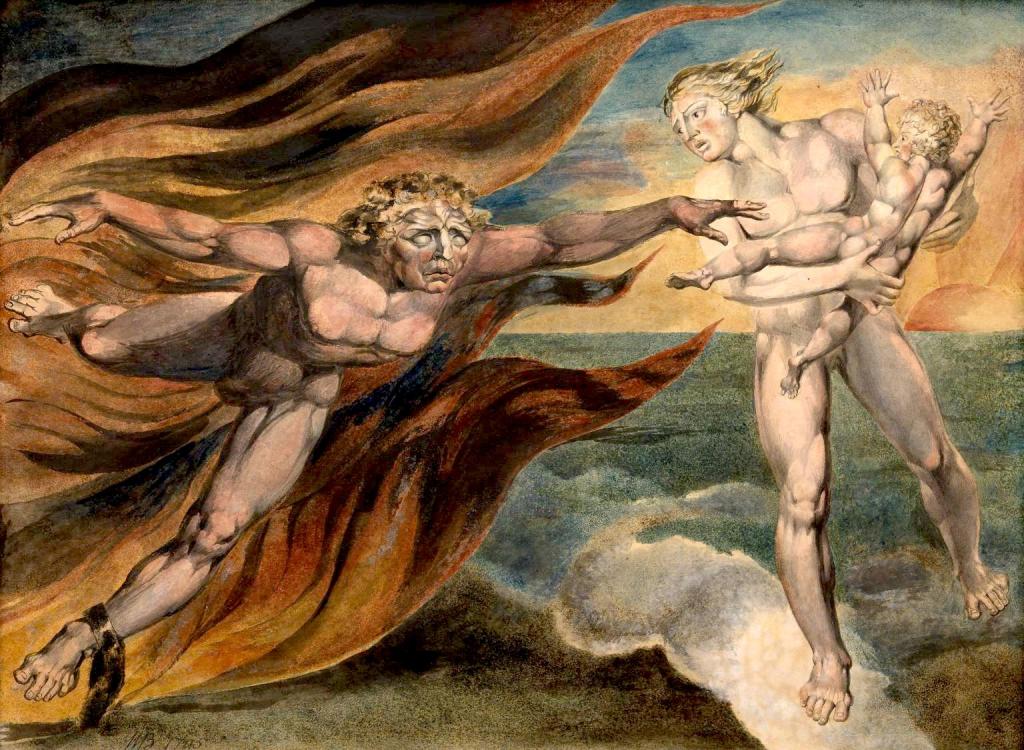

So, no, not all politicians are the same, and not even all elections are the same. But for all its surface complications, May 9 truly and inevitably comes down to a simple choice: that between good and evil—between those who stand for truth, freedom, justice, and the public interest and those who side with falsehood, dictatorship, oppression, and corruption. If you can’t distinguish between the two, or refuse to, or prefer to obfuscate the matter by repackaging it into, say, a war between families or between winners and losers, then you have a problem.

This isn’t just self-righteousness; it’s righteousness, period. You can’t justify preferring evil because of some perceived shortcoming in the good. It’s in the nature of things that “the good” will forever be imperfect, forever a work-in-progress. It can be clumsy, patchy, plodding, long drawn out, and sometimes, if not often, it will lose skirmishes and battles to the enemy; fighting for it can be wearying and dispiriting. On the other hand, evil is well thought-out, comprehensive, well-funded, and efficient; it can attract hordes to its ranks, and promise quick victory and material rewards. Evil is often more fascinating and mediagenic, from Milton’s Lucifer to Hitler and this century’s despots. But none of that will still make it the right choice.

Commentators have pointed out that Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s embattled president, may not be the shining hero that the media has served him up to be, because he had repressed his enemies before the Russian invasion and had established links with neo-Nazi groups. Now that may well be true, although it will be hard to believe that the Zelensky that emerges out of this crisis—if he does—will be the same man he was before.

But none of that excuses Vladimir Putin’s murderous rampage, nor elevates his moral standing, nor permits us to turn our eyes away from the carnage in the smoking rubble. The “Western media” and “Big Tech”—the favorite targets of despots, denialists, and conspiracists—may have their problematic biases, but only the radically lobotomized will accept the alternative, which is the Chinese, Russian, and North Korean interpretation of what constitutes journalism, and of an Internet within a net.

We cannot let the imperfections or even the failures of the good lead us to believe that evil is better and acceptable. You don’t even have to be saintly to be good. If you’ve led a life of poor decisions, making the right one this time could be your redemption. There are far worse and darker crimes than self-righteousness in others.