Qwertyman for Monday, November 24, 2025

I”M NOT a historian, although there are times I wish I were, and at an early crossroads in my youth, I actually had to choose between Literature and History for my major, settling for the former only because I thought I could finish it faster. But I’ve retained a lifelong interest in history, for the treasure trove of stories to be found in the past and for what those stories might foretell of the future.

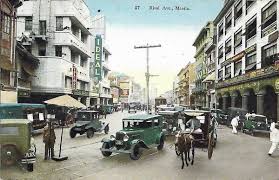

I’m particularly fascinated by the prewar period—what Filipinos of the midcentury looked back on as “peacetime” and what Carmen Guerrero Nakpil called our “fifty years in Hollywood,” which were enough to occlude much of the influence of our “three hundred fifty years in a convent” under the Spanish. It was an age of many transitions, from the jota to jazz, from the caruaje to the Chevrolet, from tradition to that liberative and all-embracing buzzword, the “modern.” Much of that went up in smoke during the Second World War, but you can still catch the ghost of this lost world on the Escolta, among other vestiges of our love-hate affair with America. (You might want to visit the Art Deco exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Arts, ongoing until May 2026; I have some items on display there.)

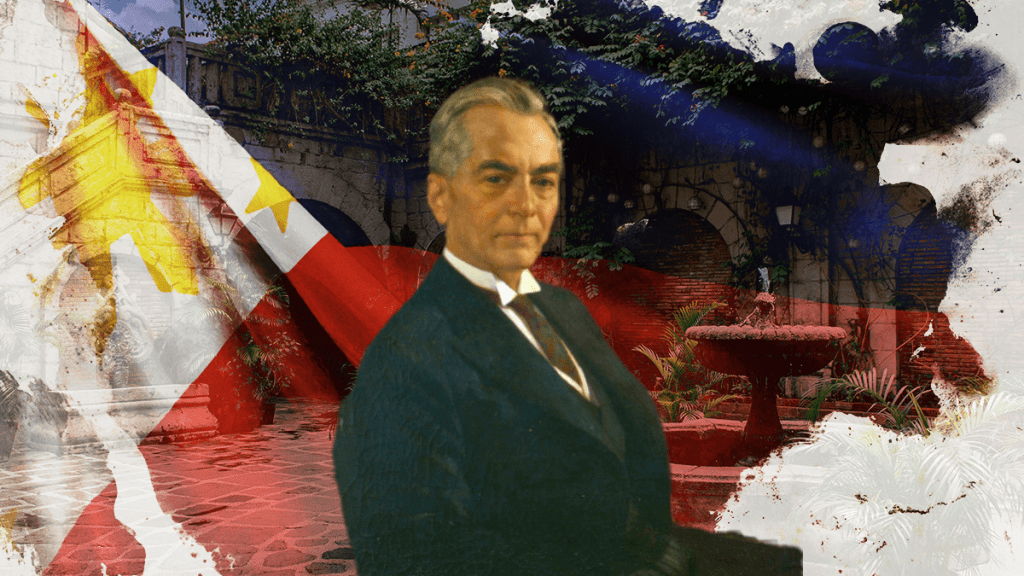

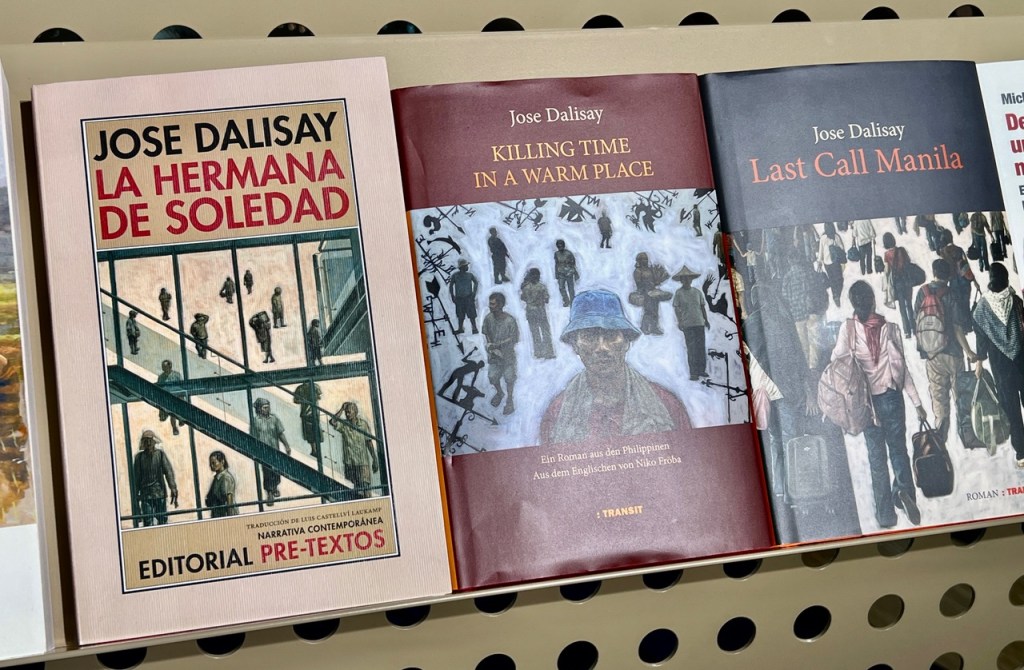

So entranced have I been by this time that I decided, during the pandemic, to set my third novel in it, at the birth of the Commonwealth and upon Quezon’s assumption of ultimate power, an upstairs-downstairs narrative about the comprador upper class and the world of the Manila Carnival set against the embers of the Sakdal uprising, the fuming and scheming Aguinaldistas, and the netherworld of printing-press Marxists and tranvia pickpockets. Progress has been slow because novels always take the back seat to life’s more pressing needs, but I still hope to get this done if it’s the last thing I do.

The research for the book, however, has brought its own rewards. Among my main sources for the background has been a slim volume—long out of print and now very hard to find—titled The Radical Left on the Eve of War: A Political Memoir by James S. Allen (Quezon City: Foundation for Nationalist Studies, 1985). Allen (actually a pseudonym for Sol Auerbach) was an American scholar and journalist, an avowed Marxist who traveled to the Philippines in 1936 and 1938 with his wife Isabelle, also a member of the American Communist Party, to meet with local communists and socialists (then headed by Crisanto Evangelista and Pedro Abad Santos, respectively) and to get a sense of the Philippine situation under American rule.

Even that early, the threat of a Japanese invasion was already looming on the horizon and causing great anxiety in the Philippines; Japan had earlier occupied Manchuria and as much as a quarter of the entirety of China by 1937. It seemed like a confrontation between Japan and the United States was inevitable, although some Filipino nationalists—fiercely anti-American—preferred to ally themselves with their fellow Asians than with prolonged white rule. At the same time, others like Pedro Abad Santos feared that the independence Quezon sought would be granted prematurely to give the US an excuse to abandon the islands and avoid confronting the Japanese.

This is where I tell you why I’m bringing up James Allen’s memoirs this Monday—because of our present situation vis-à-vis China and (in one of history’s ironic reversals from victim to victimizer) its growing domination of the South China Sea. In Quezon, Filipinos had a leader who was deeply mistrusted and opposed by many; the United States’ willingness to defend the Philippines was in doubt; and the threat of a foreign invasion was clear and imminent.

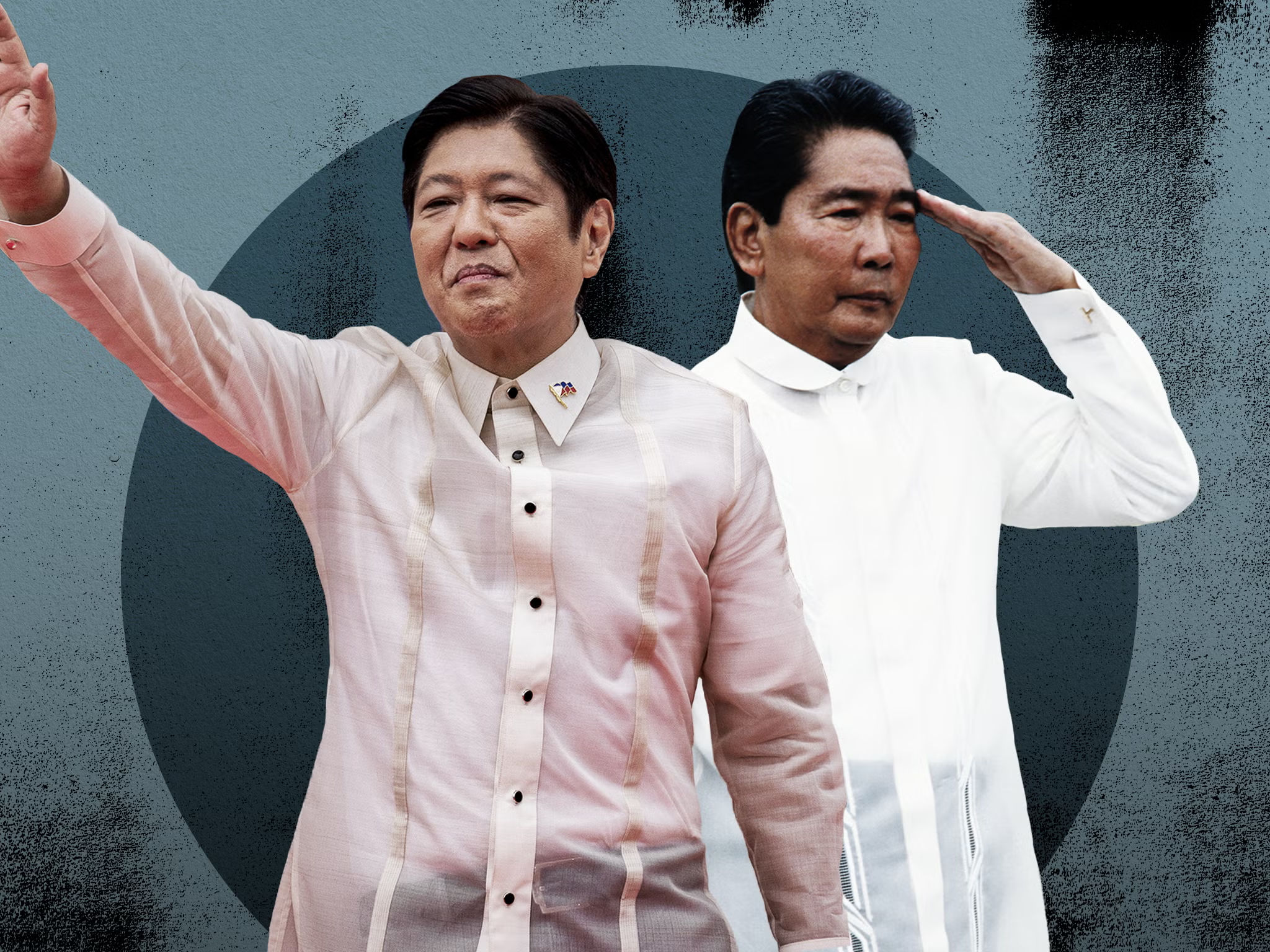

Allen actually sat down with Quezon for a long interview at the latter’s invitation, and was impressed by the man’s grasp of politics and his singular ambition. But the article that came out of that encounter displeased MLQ; Allen, after all, was still a communist at heart, which makes the following quotation—from a letter Allen would compose and send to his American colleagues in October 1937—even more interesting. I’ll leave it to you to observe the parallels, and to cast them against the Marcos-Duterte issues of our time.

“Filipino Marxists and radicals need to relate independence from the United States to the world crisis created by fascism. The immediate concern in the struggle for an independent and democratic Philippines is to safeguard the country against the threat of Japanese aggression. The objectives of complete independence from the United States and the internal democratic transformation must be obtained without endangering such gains as have been made or subjecting the country to new masters. The people must be awakened to the prime and pressing danger to their national existence. The United States is moving toward alignment with the democratic powers against the fascist bloc, albeit slowly and indecisively.

“Roosevelt is shifting somewhat toward the Left of Center to keep pace with his mass support from the surging labor movement and anti-fascist and anti-war popular sentiment. The national interests of the Philippines call for vigilance and precautions against Japanese aggression. This coincides with the interests of the United States in the Pacific area, and it would be folly not to take full advantage of this concurrence. In the broader perspective, the outcome of the struggle in China will be crucial for all the peoples of the Far East, and if the United States were to withdraw from the Philippines this would be a serious blow against China and encouragement to Japan’s designs upon Southeast Asia and the islands of the Pacific. The cause of Philippine independence at this time can best be served by cooperation with the United States.

“The situation also requires a change in the attitude toward Quezon, from frontal attack to critical support. Unprincipled opposition for the sake of opposition-as with some leading participants in the Popular Alliance is dangerous, for it plays into the hand of pro-Japanese elements and sentiments. Quezon certainly is not an anti-fascist, but he is not intriguing behind the scenes with Japan. The greatest opposition to his early independence plan comes from the landed proprietors, particularly the sugar barons, while it enjoys support among the people. The Popular Alliance should also support the plan, including provisions for mutually satisfactory economic, military and diplomatic collaboration after independence. Though Quezon is far from being a Cardenas or Roosevelt in his domestic policies, every effort should be made to move him away from his pro-fascist and land baron support by providing him with mass backing for such pro-labor and progressive measures as are included in his social justice program. In sum, the Popular Alliance should encourage a national democratic front devoted to the preservation of peace in the Pacific, the safeguarding of Philippine independence, and defense and extension of democracy in the country.”