Qwertyman for Monday, January 6, 2025

I’M WRITING this on New Year’s Day in San Diego, California, where we’ve been visiting our married daughter Demi, who’s been living and working here for the past seventeen years. It was our first Christmas in America in ten years, and our second visit since the pandemic ended.

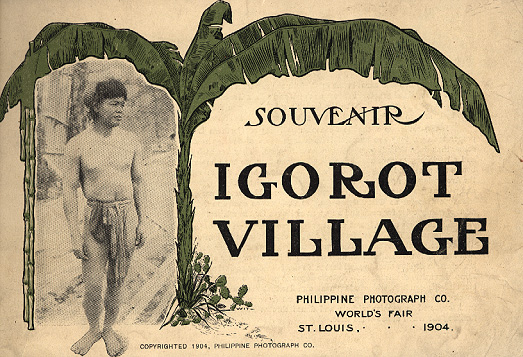

Last night, just before midnight on New Year’s Eve, I watched a long and fascinating documentary on cable TV on the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, which ran from April to December that year. We Filipinos recall that event for its importation of over 1,000 of our countrymen to demonstrate what “savagery” meant—specifically, through the public butchering and eating of dogs.

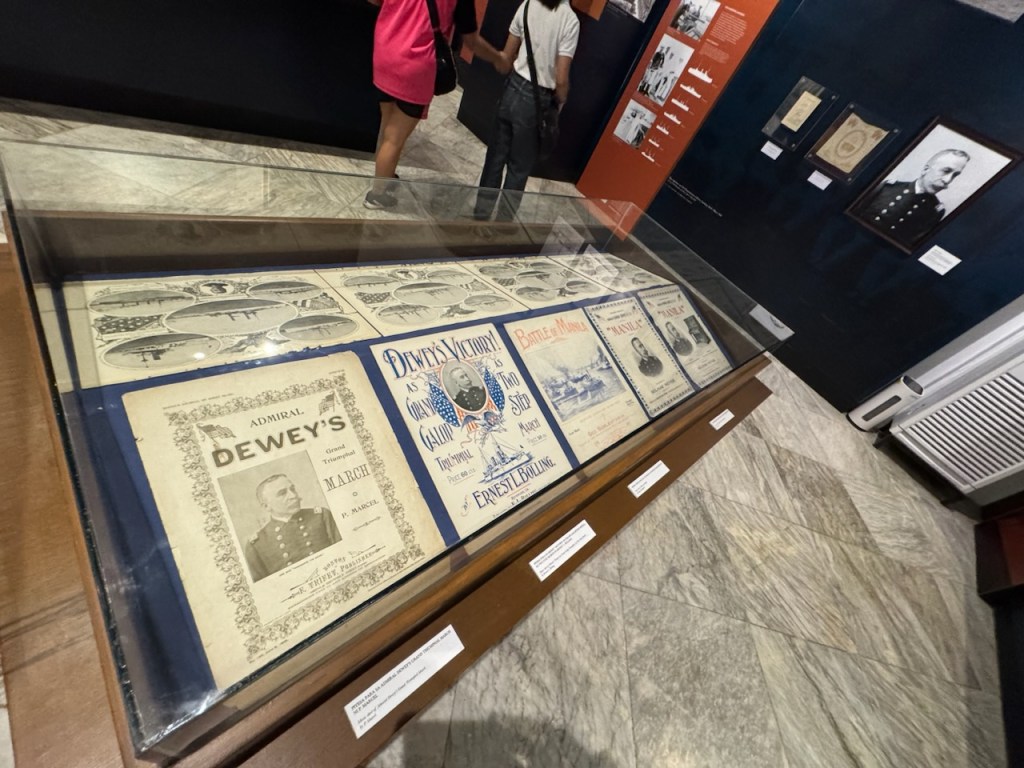

That bloody sideshow raised an outcry even then among both Filipinos and Americans, a pain we still feel more than 120 years after. Lost to many of us as a result of that diversion was the magnificence of the fair in many other respects, especially in terms of advances in science and technology. Many necessities and amenities we associate with the 20th century—electrical lighting, wireless telegraphy, the X-ray machine, baby incubators, and tabletop stoves, among others—were first shown to the public at the fair.

But the fair, above all, was meant to showcase American ascendancy in politics and culture and in military and industrial might. America had just defeated Spain and had become a global maritime power, and was eager to flex its muscle, so this triumphalism underscored the great urge at St. Louis to introduce the world to America, and America to the world.

Just a few days earlier, we came out to San Diego’s famous waterfront to watch a parade to celebrate the Holiday Bowl, a football game scheduled for the Christmas break, with floats, balloons, marching bands, and military vehicles. It was a moment of pure Americana, brimming with Christmas cheer. I did my best to keep politics out of my mind for that golden hour, but of course it was never far away—especially in San Diego, a border city that could soon find itself caught in the mass-deportation drama promised by the incoming Trump administration, which takes office in less than three weeks.

This morning we woke up to the news of at least ten people being killed and dozens more injured on the street in New Orleans by an ISIS sympathizer plowing into a crowd of New Year revelers. That could very easily have been us at the parade, and again I had to wonder if—despite all the bad press the Philippines gets, with some reason—the US was truly a safer place, given its new realities of normalized and often racist violence.

It doesn’t even take a bearded terrorist to wreak havoc in American life; as of December 17 last year, 488 mass shootings had been recorded in the US, so often that they’ve become a news staple eliciting just about as much outrage and action as another mugging at Central Park. Anti-Asian violence—to include both physical assaults and verbal or online abuse—has been on the rise, with Southeast Asians reporting the highest number of threats, despite polls showing most Americans believing that anti-Asian-American attitudes are on the wane, post-pandemic.

That’s not going to deter the hundreds of thousands of Pinoys who, like us, still need or want to visit America each year—mostly as tourists who just want to see Disneyland, the Golden Gate Bridge, and the Empire State Building, aside from picking apples in Michigan, tasting wine in Napa Valley, and skiing in Colorado. The magic of an America we fantasized about—growing up watching Hollywood movies, listening to American songs, reading American books, and following American idols—remains powerfully attractive, enhanced by an image we retain of America as an innocent, benign, and giving place. This might be especially true of us Boomers who learned about snow and white Christmases long before we came across the real thing.

I doubt, of course, that our forebears who stood half-naked in their tribal garb for the delectation of the crowd in St. Louis saw anything so warm and fuzzy about America. Instead they saw curiosity, pity, and revulsion. American “innocence” was always a romantic illusion; America the Beautiful can turn on a dime to become America the Ugly.

When I put all these things together in my mind, I wonder if we 21st-century Filipinos identify more ourselves today with those “savages” on exhibit or with their onlookers, particularly those Pinoys who have crossed over to become Americans—in some cases, even “more American than the Americans,” as I’ve heard it said, proud of their assimilation into a mainstream moving farther than ever to the political right.

As a teacher of American literature and society—who also studied, taught, and worked in the Midwestern heartland for many years—one thing I always remind my Filipino students is that there’s no such thing as a single, monolithic America, and that, whatever its current majorities might say, American society is diverse and ever more diversifying. To the American right, that’s the “great replacement theory” at work, the horrifying possibility that non-whites—the carnival freaks—are taking over the country, prompting the Trumpist turnaround from “diversity, equity, and inclusion” or DEI policies. To me, diversity offers both challenge and hope.

Out of respect for my hosts and friends here in San Diego—some of whom, for their own reasons, voted for Donald Trump—I’ve held my tongue for the time being, telling myself that it’s their country and their choice, although that choice will inevitably affect our lives halfway around the world.

Among my liberal American friends, I sense an urge to disconnect at least temporarily from political reality and to go into passive resistance while they regroup. It’s a position that I can identify and sympathize with, as we sort out our options in the Philippines of 2025. We survived martial law; you’ll survive Donald Trump, I tell them. To survive may well be our best New Year’s resolution: against the aggravations and vexations of the world we’ve come into, survival is the best revenge.