Penman for Sunday, September 7, 2025

IT’S ALMOST criminal to admit this, given the understandable outpouring of grief and adulation that followed the announcement of film director Mike de Leon’s recent passing. But the truth is, I didn’t really know him or his work all that well. I’d seen a few of his movies—Kisapmata and Citizen Jake come to mind—but for some reason missed out on the best and most celebrated ones: Batch 81, Sister Stella L, Kung Mangarap Ka’t Magising, and so on. I shouldn’t have, but there it is, like all the great books I never got to read, because I was busy doing something else.

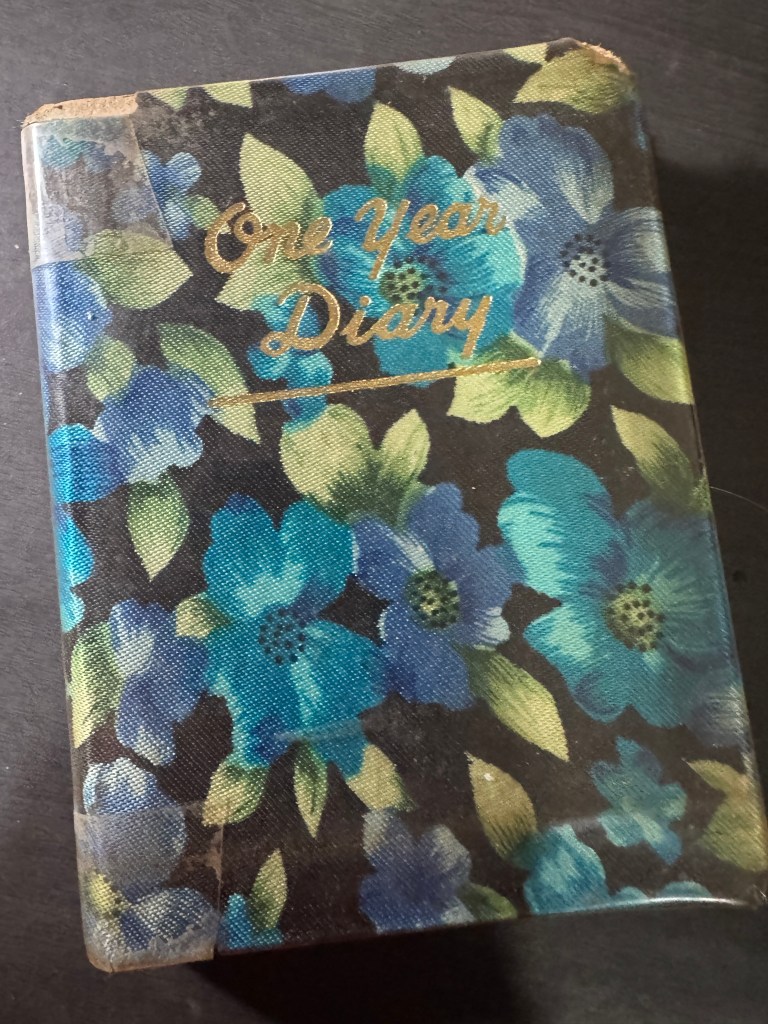

From the late 1970s to the early 2000s, I was writing scripts for many directors—mostly Lino Brocka, but also Celso Ad. Castillo, Marilou Diaz Abaya, Laurice Guillen, Gil Portes, and Joel Lamangan. (Never for Ishmael Bernal, either, nor for Eddie Romero; they’re all gone now except for Laurice and Joel.) Mike de Leon was and remained a mystery—until, on December 30, 2022, from out of the blue, I got this message in my inbox (I’ll be excerpting Mike’s messages to me from hereon; he typically writes in lowercase but I’ve edited everything):

Butch,

We’ve never met but I guess we know of each other.

I just wanted to know if you are interested in working with me on a possible screenplay that I hope I can still turn into a film even at my late age (going on 76, Stage 4 prostate cancer, but still able to function).

I admit I have never seen any of the films you made with Lino, and the only book of yours that I have is The Lavas which I have largely forgotten. But in that anthology book, Manila Noir, I found your short story, “The Professor’s Wife” the best of the lot.

The only thing I can say about my film idea is that it is part of my memories as a young boy during summer months in Baguio in the late 1950s. In other words, it is just about a group of rich people who play mahjong and the battalion of maids and drivers who serve them. This is probably the result of the flood of memories that are still spilling out of my mind after completing my book Last Look Back. It is no big production because it is the characters I am most interested in. A picture of the members of the idle rich when Baguio was still the exclusive enclave of the privileged elite, from which I’ve descended, of course.

I did ask Sarge Lacuesta and he was quite interested but he is going to direct his first film for Cinemalaya. So I picked up Manila Noir again and looked for that story and found out that it was you who wrote it.

Anyway, as I always say, suntok sa buwan. Baka hindi rin matuloy because of my health but I’d like to give it a try anyway. If you think you might be interested, please email me back.

I wrote him back to say that of course I was happy and honored to be asked to work with him:

The project sounds like something I’d be very comfortable with—a quiet family drama with an upstairs-downstairs element to it. Coincidentally, i’ve been working on a novel set in 1936 in one of those Dewey Boulevard mansions, with the Manila Carnival (and Quezon and Sakdalistas in the background). But that’s at least still another year from being done. I just wanted to say that the idea of revisiting the past to show how it has shaped the present—throwing light and shadow where they belong—is dear to me.

And now, the inevitable hitch: I’m working on three commissioned book projects at the same time, and these books will be due in 2023. I’m retired, but I’m also writing columns for the Star and teach one graduate class in UP.

I can imagine from your situation that this project is a matter of great personal significance and urgency to you—which is why I so want to be a part of it, despite my own load. At the same time, I don’t want to be a hindrance to you, especially if you want this done soonest. If you just need me to flesh out some scenes and develop some ideas and write up the sequences and dialogue as we go along, maybe we can do something together. Let the thing grow and go where it will.

Then he sent me more notes about what he had in mind:

As you probably know by now, I like shooting a film in Baguio. I now own the former family house and I’ve restored it and maintained it well. It can still pass for an authentic American colonial house of the late 1950s. Actually, the house was built in the 1930s, but I’m not sure of the exact date until I find the papers. The original owner was an American officer named Emil Speth. He married one or two native women and was the vice-mayor of Baguio when the Japanese bombed the city on December 8, 1941. Quezon was in the mansion and I read an account that Speth asked Quezon to take shelter in his house (maybe not the same one because Speth owned many houses) because he had a bomb shelter.

By the way, this is not an autobiographical film. It’s the mahjongistas I’m more intrigued about. I used to watch them with a fascination because it was not really gambling but a form of social intercourse with its own rituals.

Within a few days, much to his surprise, I emailed him back with a full storyline based on what he said he wanted to do. I’ve always been a fast writer, and I guess it was one of those things I would be known in the trade for. I delivered quickly, without fuss, just needing to be paid.

He responded:

Quite surprised to get this email and story idea. I just read it quickly but I will read it more carefully in a while, when I’m wide awake. It seems too complex, the characters as well. I was thinking of more opaque characters (from the point of view of the young boy, and the viewer, they cannot explain their behavior, that is what I’m looking for). His memories are speculative and will probably remain so until his old age. By which time, most of them are dead anyway. But I’m amazed at how you put this story together. Give me a couple of days to react to it and I will jot down my own notes.

On January 9, in the New Year, began what would become a painful series of revelations:

Sorry for the late reply. I’ve not been feeling well, possibly because of the gloomy rainy weather. I can’t take my regular early morning walks around Horseshoe or Greenhills. Also, I’m kinda antsy about my scheduled PET scan next week. My doctors told me last year, after the first PET scan, that I may not live another eight months or so, but it’s been more than a year and I’m still here. Fortunately, I was able to finish my book.

I am writing my “impressions” of what I feel the film should be or “feel.” One important thing is that I think the film should start in medias res, the family is already in Baguio, several weeks in fact. The kids are playing or doing what they usually do (perhaps a little bored) and mahjong sessions are ongoing. I don’t want to give them family names, just Tita Rita, Tito Hector, Nicky (the kid).

I think I need to paint a more vivid picture of what life was like back then for your benefit. I’m selecting photos of my youth in Baguio and sending them to you. I would like to give the impression that the film is “almost” biographical but not entirely so. So please give me another week to put something together. So there can be nothing like a murder. Psychological violence is more interesting to me.

Pahinga muna ako, I’m always tired.

A couple of weeks later, he followed through:

Sorry for the long silence. I’m pondering a lot of things at the moment. I haven’t written anything but the concept keeps growing in my mind that it is becoming unfeasible. I finished reading a book on the 1950s and I started reading “Cameo” last night, and I really like the way you write.

Don’t hold me to this but I’m thinking that “The Professor’s Wife” may be the right kind of film for me but I was wondering if it can be set in Baguio. Not in my house, of course, it’s too grand for the story. I have some very dear friends in Baguio who may help me look for the right location for the story.

I’ve been asking myself the same question over and over, do I still want to make films? It’s not just my health but a lot of other things.

I’m sorry if I seem very unpredictable but I feel you can understand and empathize with my situation. I thought I’d be dead by now, but I’m not.

And then:

Sorry for the long silence. My new PET scan results are not very encouraging. Although the bone metastasis has not spread (from the prostate cancer), there is worrisome new activity in my liver that was not there before. I will have to undergo a liver biopsy, an outpatient procedure but my doctor wants to have me admitted. And if I can do this early next week, it takes a week for conclusive results to come out.

So that kinda leaves in a kind of limbo. In many ways, I feel so vulnerable, something that I did not feel when I was first diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2016. I feel that my life has just stopped. Anyway, the story I’m most interested in now is the aborted script of my own “Unfinished Business,” or its new title “Sa Bisperas” for obvious reasons. I was beginning to make major revisions when Bongbong was elected, but now it seems very appropriate to my life—an existential film masquerading as a ghost story.

Sorry about all of this, butch. I will keep you updated. Perhaps we can co-write the revisions if you are open to that sort of thing. But in the meantime, I have to try to beat this thing.

In January 2024, a year after our first contact, he wrote me:

I hope you’re doing fine and I’m really sorry for the long silence. So much is happening in my life right now but I’m still hoping to make one more film next year, that is if my medical condition doesn’t take a turn for the worse.

I was wondering if anyone has made a film of your short story “The Professor’s Wife”, included in Manila Noir. I’ve been thinking about it and it could be something I can still do. If it’s possible, I can option it for a certain period and pay whatever you feel is a good price. The same would go for the screenplay—that you will be paid whether I can make it or not. I think it has the potential to become a small but intimate and intense film, character-based, with a murder thrown in, like Kisapmata.

I wrote and sent him a full storyline based on my short story, but told him that I wasn’t going to bill him for anything until the project was actually underway. Six months later, on July 10, he wrote:

There are a couple of questions I should ask you right away. The professors’ academic argument, could it be about some “obscure” historical event or incident like something set during the Japanese Occupation? Perhaps an issue of collaboration. That way, we can subtly bring in the political situation today.

Is it still possible to shoot in UP? Or in some relatively quiet location at the teachers’ village, so I can record direct sound, and avoid dubbing. It would be wonderful to set the story in Baguio, but I don’t want to force it.

I’m going to travel in Europe in November, perhaps for the last time. My excuse is the restoration of Sister stella which is currently being restored in Bologna. I don’t have a Schengen visa and an invitation from my friend Davide of Ritrovata may help a lot in getting me one and for my caregiver as well.

He wrote later about visiting our home on the campus, where my story was set:

I think a visit to your place would help me tremendously. There are so many possibilities to this story and since this is the first time we’re working together, I must warn you, makulit ako. But at least this time, the germ is there, the story is there. I just want to know more about the milieu.

It’s a noir film and a social drama at the same time, I think. As I was writing, I was thinking of Cornell Woolrich, James M. Cain, and even Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley series or the Cry of the Owl, yata. Are you familiar with the 1947 film “Out of the Past” by Jacques Tourneur?

I will continue to write down my rambling notes and send them to you in a day or two.

He came to the house on July 29, 2024. It was only the second—and would be the last—time for us to meet. We had a pleasant chat over a light merienda prepared by Beng in our garden gazebo in UP. I can’t recall if he even touched the food; he looked pale against his usual black shirt, but then he always seemed to be like that. We discussed the revisions I was thinking of making on my story to shade it even further. He said that he found me refreshingly easy to talk to, which I was happy to hear, but at the same time we were both aware that we were dreaming up a film neither of us would get to see.

On October 12, 2024, I got the message I could not be surprised by. I wrote back to wish him well.

I’m sorry I have to write you this email, wherever you are. I’ve been quite sick these last two weeks. I was in the hospital for several days for a blood transfusion.

My recovery will be slow, according to my doctors. But they don’t really have to tell me that. I’ve been very weak, most probably due to a multitude of causes, foremost among them is the metastasis caused by prostate cancer.

Needless to say, I don’t think I will be able to make a film, so you might as well know now. I even had to cancel my trip to Europe. I’m sorry that I wasted your time. I hope you understand.

Best and thank you very much

Mike