Qwertyman for Monday, December 2, 2024

FOLLOWING THROUGH on last week’s piece about the challenges faced by creative writers trying to make a living in this country, let me share some further thoughts on that topic that I wove into my Rizal Lecture last week at the annual congress of Philippine PEN. My talk was titled “The Living Is in the Writing: Notes on the Profession of Writing in the Philippines.”

Our writers of old made a profession of writing, often by working as journalists, speechwriters, and PR people at the same time that they wrote poems, stories, novels, and essays on the side. Some also taught, and of course some writing comes with that territory, but with teaching you get paid for your classroom hours than for your word count. (To which I should also add, so much of the writing that our literature professors do today is understandable only to themselves.)

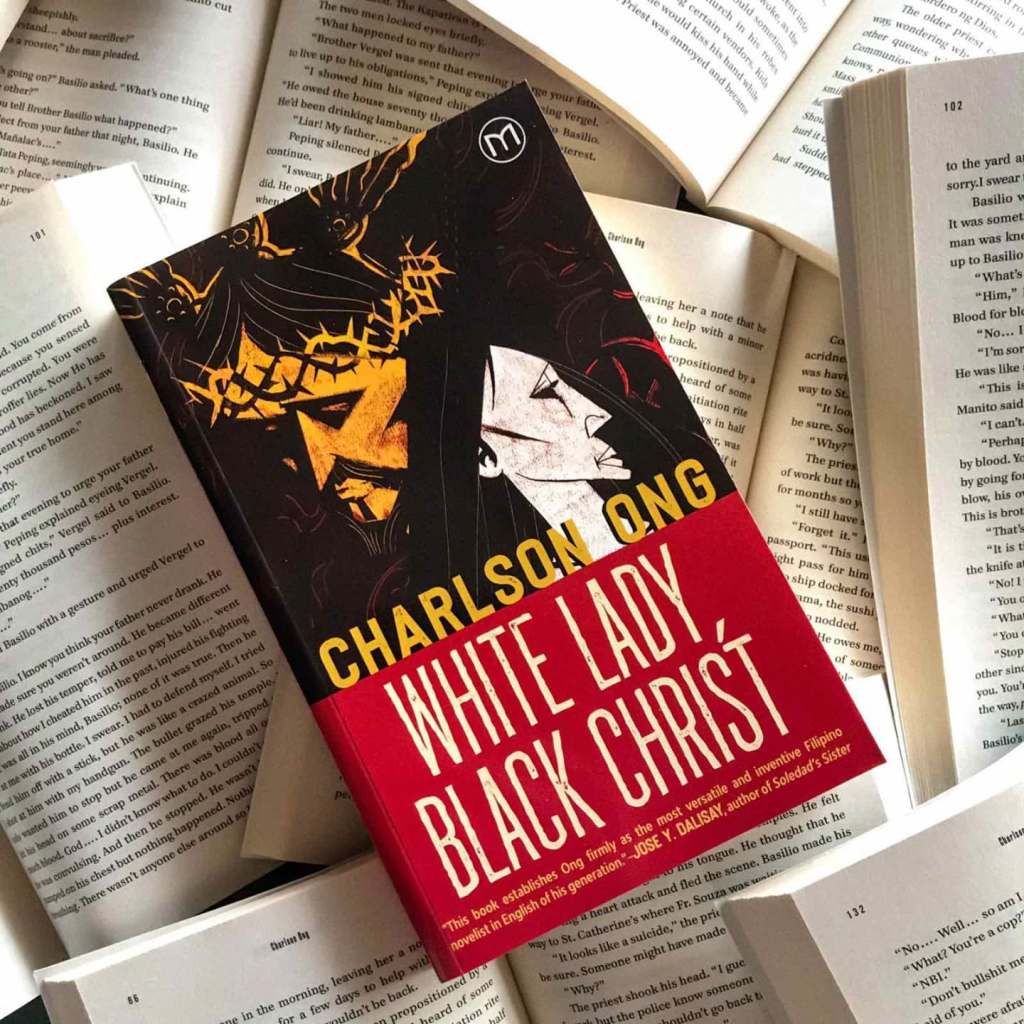

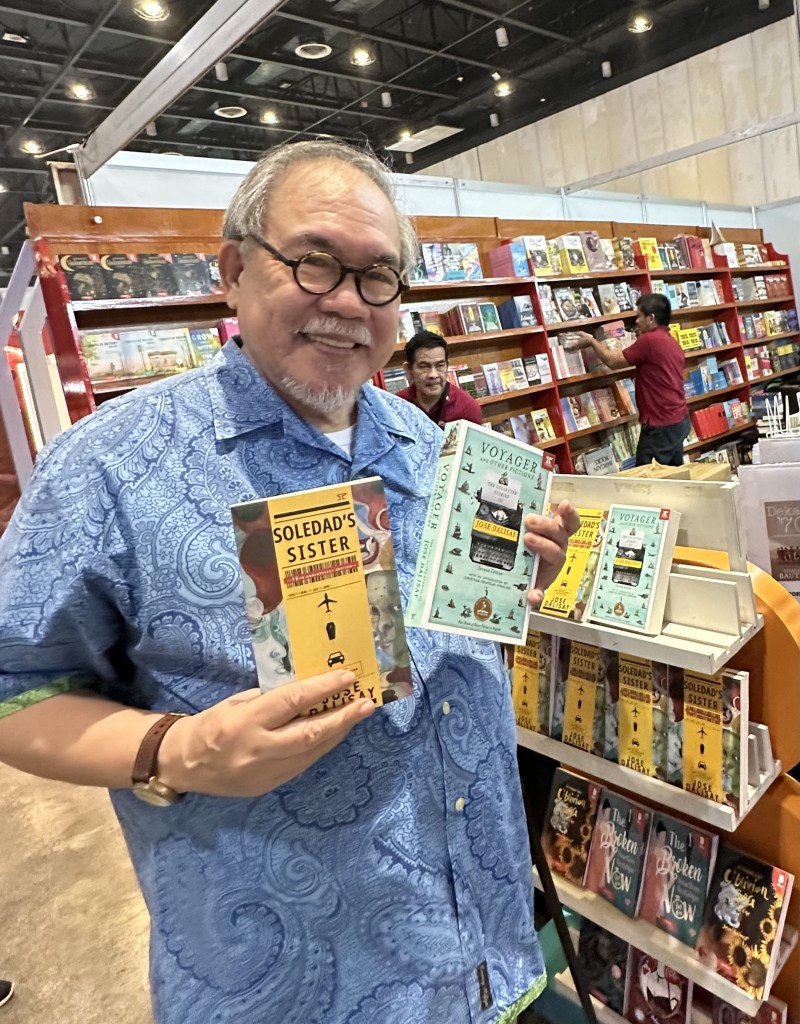

Our best and most prolific writers lived by the word and died by it. The two who probably best exemplified this kind of commitment to writing—and nothing but writing—were Nick Joaquin and his good friend Frankie Sionil Jose. Both were journalists and fictionists (in Joaquin’s case, a poet and playwright as well). We can say the same for Carmen Guerrero Nakpil and Kerima Polotan, as well as for Gregorio Brillantes, Jose Lacaba, Ricky Lee, Alfred Yuson, Cristina Pantoja-Hidalgo, and Charlson Ong, among others.

These were all writers whom you never heard to claim, as has been recent practice, that “I am a poet!” or “I am a fictionist!” They were all just writers, for whom the practice of words was one natural and seamless continuum, and a profession they mastered just as well as we expect doctors, engineers, mechanics, and lawyers to do. This was also when journalists could be poets who could also be politicians and even reformers, revolutionaries, and heroes.

This was paralleled in other arts such as painting, where artists such as Juan Luna, Fernando Amorsolo, and Botong Francisco routinely accepted commissions to support themselves and any other personal undertakings. (Of course, this was well within the old Western tradition of writers and artists having wealthy patrons to help keep them alive and productive.)

But then came a time when, for some reason, creative and professional writing began to diverge, as creative writing withdrew from the popular sphere and became lodged in academia, where it largely remains today. Professional writing, or writing for, money, came to be seen as the work of hacks, devoid of art and honor. Even George Orwell urged writers to take on non-literary jobs such as banking and insurance—which incidentally T.S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens did, respectively—rather than what he called “semi-creative jobs” like teaching and journalism, which he felt was beneath them. (Orwell himself worked as a dishwasher in Paris, where he wryly observed that “nothing unusual for a waiter to wash his face in the water in which clean crockery was rinsing. But the customers saw nothing of this.”)

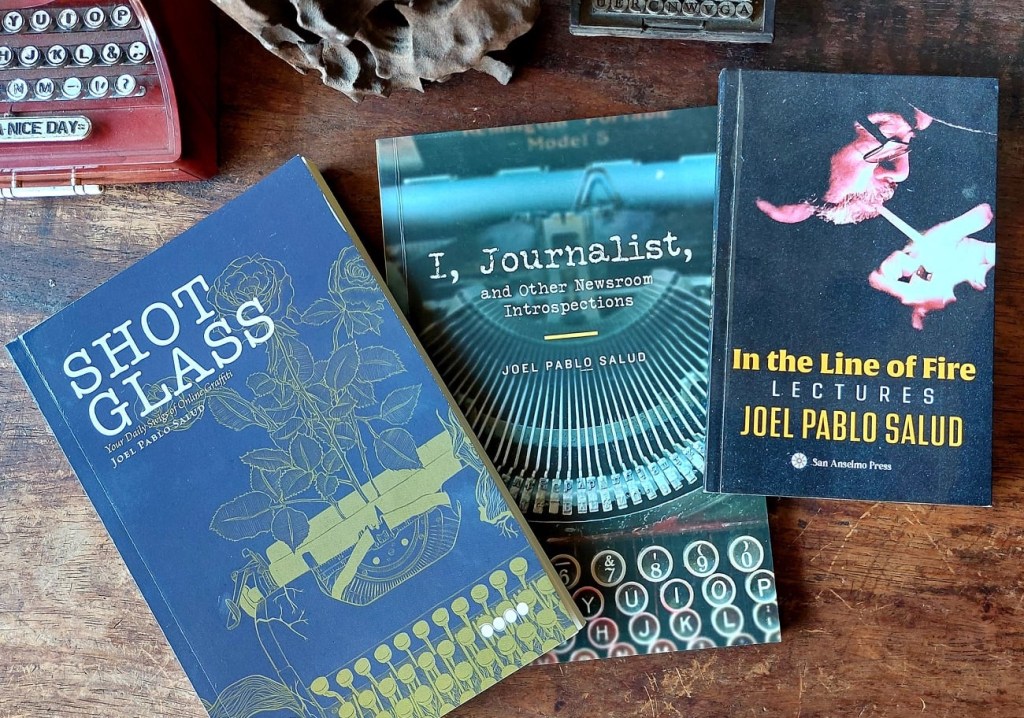

An attitude of condescension soon emerged among poets and fictionists who looked down on journalists as a lesser breed—something I have always warned my students against, having been a journalist who had to turn in a story, any story, by 2 pm every day on pain of losing my job. Never knock journalists. Let’s not forget that when it comes to facing real dangers brought on by one’s written word, poets and fictionists have it easy. The last Filipino novelist who was shot for what he wrote was Jose Rizal; the only writers dying today are our journalists and broadcasters in the hinterlands offending the local poobahs. Governors and generals read newspapers, not novels; they are impervious to metaphor.

Professional writers, on the other hand, saw creative writers as artsy dilettantes enchanted by fancy words and phrases that no one else understood and very few people paid for. Creative writers took it as a given that they were wedded to a life of monastic penury, unless they had another skill or job like teaching, doctoring or lawyering, or marrying into wealth. It even became a badge of honor of sorts to languish in financial distress while reaping all manner of writing honors, in the misguided notion that starving artists produced the finest and most honest work.

The fact is, both are two sides of the same coin, which is the currency of public persuasion through words and language. One is an artist, the master of design; the other is the artisan or craftsman, the master of execution. Both can reside in the same person, unless you’re foolish enough to disdain one or the other. You can produce great art, if you have the talent, the discipline, and the hubris for it; but you can also live off your artistic skills, if you have the talent, the discipline, and the humility for it.

(That said, I have to report that in my forty years of teaching creative writing, some of the students who find it hardest to switch to fiction are journalists, who just can’t let go of the gritty and often linear reality they’ve been accustomed to; poets come next, those who feel preciousness in every word and turn of phrase, so much that they can’t move from one page to the next without agonizing, or, going the other way, without drowning us in verbiage.)

This was why, more than twenty years ago, I designed and began teaching an undergraduate course at the University of the Philippines called “CW198—Professional Writing.” Mainly intended for Creative Writing and English majors who had very little idea of their career options after college aside from teaching, the course syllabus includes everything from business letters, news, interviews, and features to brochures, scripts, speeches, editing, publishing, and professional ethics. The first thing I tell them on Day One is this: “There is writing that you do for yourself, and writing that you do for others. Don’t ever get the two mixed up.”

Penman for Monday, May 20, 2019

Penman for Monday, May 20, 2019