Qwertyman for Monday, March 9, 2026

I TRY not to get triggered by everything I read on Facebook—half of which is probably fake or trash, but which we respond to all the same—but one recent post I just couldn’t ignore came from the Department of Education, happily announcing the removal of 15 core senior high school (SHS) subjects and their integration into five new “interdisciplinary” subjects.

The subjects removed were Oral Communication; Reading and Writing Skills; 21st Century Literature from the Philippines and the World; Media and Information Literacy; Komunikasyon at Pananaliksik sa Wika at Kulturang Filipino; Pagbasa at Pagsuri ng Iba’t-ibang Teksto Tungo sa Pananaliksik; Personal Development; Physical Education/HOPE; Statistics and Probability; Earth and Life Science; Physical Science; Understanding Culture, Politics, and Society; Contemporary Philippine Arts from the Regions; and Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person.

They will be replaced by Effective Communication/Mabisang Komunikasyon; Life and Career Skills; General Mathematics; General Science; and Pag-aaral ng Kasaysayan at Lipunang Pilipino.

The rationale for the streamlining, says the DepEd, was that “Instead of treating the old core subjects separately, the revised core subjects integrate key competencies from related disciplines and will be offered across the entire academic year—supporting more sustained, in-depth learning and an interdisciplinary approach.”

That all sounds good on the surface—the word “streamlining” is one of those managerial buzzwords that instantly evokes efficiency, waste reduction, and forward movement—but I had to wonder at the wisdom of this decision, just looking, for example, at where the arts and culture will go under the new program, and how well they will be taught and learned under their new rubrics.

I can sense a general urgency to get the kids out of school sooner, to make them employable, and to get them employed. As it is, we already added two years with K-12 to their pre-collegiate education, with many parents, politicians, and even some teachers remaining unconvinced that those extra years were really necessary, given the added expense. I’m not sure if the reduction of 15 core subjects to five has budgetary implications, or was driven by them.

What worries me, going by the subject titles, is that once again, the arts (to include literature, music, dance, the visual arts, and art appreciation) are being subsumed into topics so broad that they will lose the specificity they require to make an impact and leave an impression on the student, to make it self-evident why the arts matter in human life.

I’ve often said in this respect that for far too long, the arts and culture have been treated by our government if not society in general as forms of entertainment, as intermission numbers to lighten the implicit gravity of business, politics, and science. (The guest of honor’s boring speech, following an equally long and tedious introduction, has to be framed by lively song and dance routines to awaken the audience.)

There’s value to that, of course—the ameliorative power of art is one of its primary functions—but as the dramatist will say, comedy is dead serious business behind the laughter. While science and math strive for certainty and precision, thereby addressing the best use of our increasingly limited resources, the arts remind us of our humanity—of our innate imperfections, of our capability to doubt, to weigh and choose between this and that, such as between self-interest and the collective good.

That’s what happens when you read a good poem or novel or stand before a great painting: you begin to wonder more about yourself and your environment, about your standards of justice or beauty, about the distance between what should be or should have been and what is. Studying literature is about far more than learning communication skills (which you will, along the way)—it is, indeed, about “Life and Career Skills.”

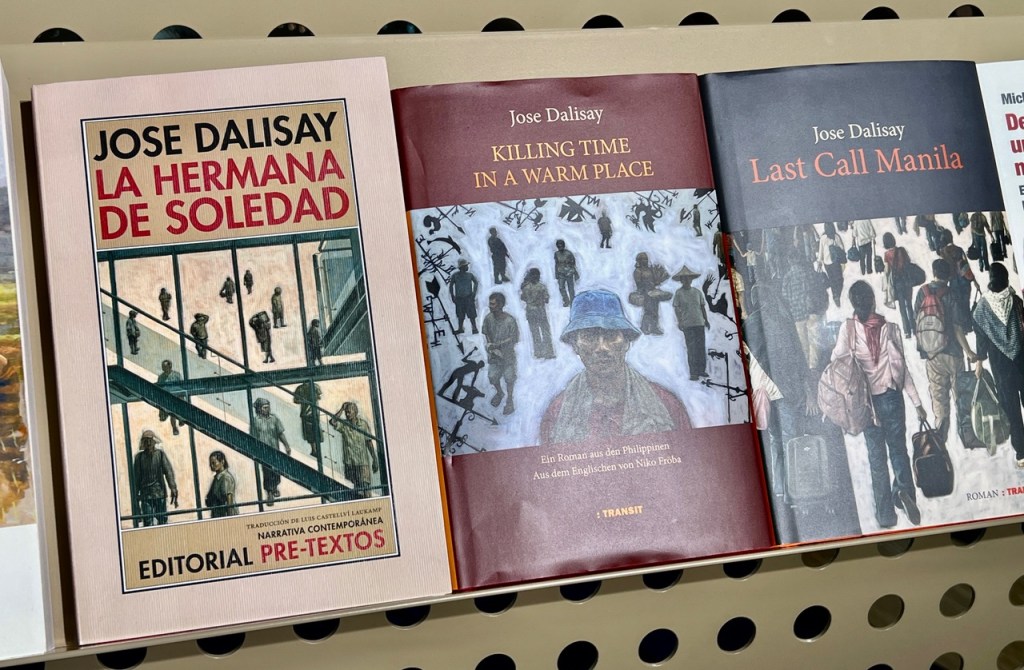

It is the arts that are inherently interdisciplinary; for example, when I discuss a short story by Manuel Arguilla, we will inevitably discuss history, geography, politics, economics, psychology, and language—while, at the same time, trying to understand the emotional experience we have just been put through. This is the specificity I mentioned earlier, which I fear will be lost in the abstractions of “interdisciplinarity.”

The EdCom II’s Final Report (Turning Point, 2026), where the SHS curricular changes are also noted, unfortunately sees this measure as mere “decongestion.” The report also tells us that the SHS streamlining will remove the dedicated Arts and Design track entirely as a recognized pathway.

At this point, I’d like to borrow some words from a good friend and one of our leading arts educators, the sculptor Toym Imao, current dean of UP’s College of Fine Arts, who also pored over the EdCom II report and came away with these observations:

“Upon reflection, something becomes very clear to me. There is no substantial national discussion of arts and culture education. The absence is not minor. It reveals a blind spot in our imagining of national reform. Why does ACaD matter now?

“This is not nostalgia but strategy: in an AI-driven era, art, culture, and design are core competencies for critical thinking, ethical judgment, and human-centered innovation.

“We are living through a time of rapid technological change. Artificial intelligence is advancing faster than most institutions can process. Social media algorithms shape taste, identity, and even memory. Culture is packaged, flattened, and circulated at high speed. Labor markets are shifting. At the same time, we have the Creative Industries Development Act, Republic Act 11904, which positions creativity and culture as economic drivers, but sadly the EDCOM 2 reports is wanting in connecting this to urgent educational reform.

“As an artist and educator, I see what this means on the ground. Artificial intelligence systems are trained on massive global datasets that largely come from powerful nations and dominant languages. These systems are not neutral. They reflect the biases, priorities, and aesthetics of where they come from.

“In a country like the Philippines, with hundreds of distinct indigenous, regional, and linguistic cultures, this has consequences. If our own students are not deeply grounded in their cultural traditions, histories, and aesthetic languages, then what fills that space will be imported, automated, and algorithmically repeated. Without strong arts and culture education, cultural knowledge slowly thins out in global digital flows. Indigenous aesthetics risk becoming raw material for data, instead of living practices.

“Students become consumers of images and narratives without the tools to question them.

“In the studio and in the classroom, I see the difference. Arts education trains the eye, the hand, and the conscience. It develops judgment, sensitivity, context, and memory. It teaches students to ask where an image comes from, who it serves, and what it erases. These are not decorative skills. They are human skills.”

I can hardly overemphasize how important this is at a time when we are being roiled by massive corruption and when moral standards collapse or vanish to the point that a president can justify extrajudicial murder and be applauded by millions. A lesson in Greek tragedy is what you need for that.