Qwertyman for Monday, June 30, 2025

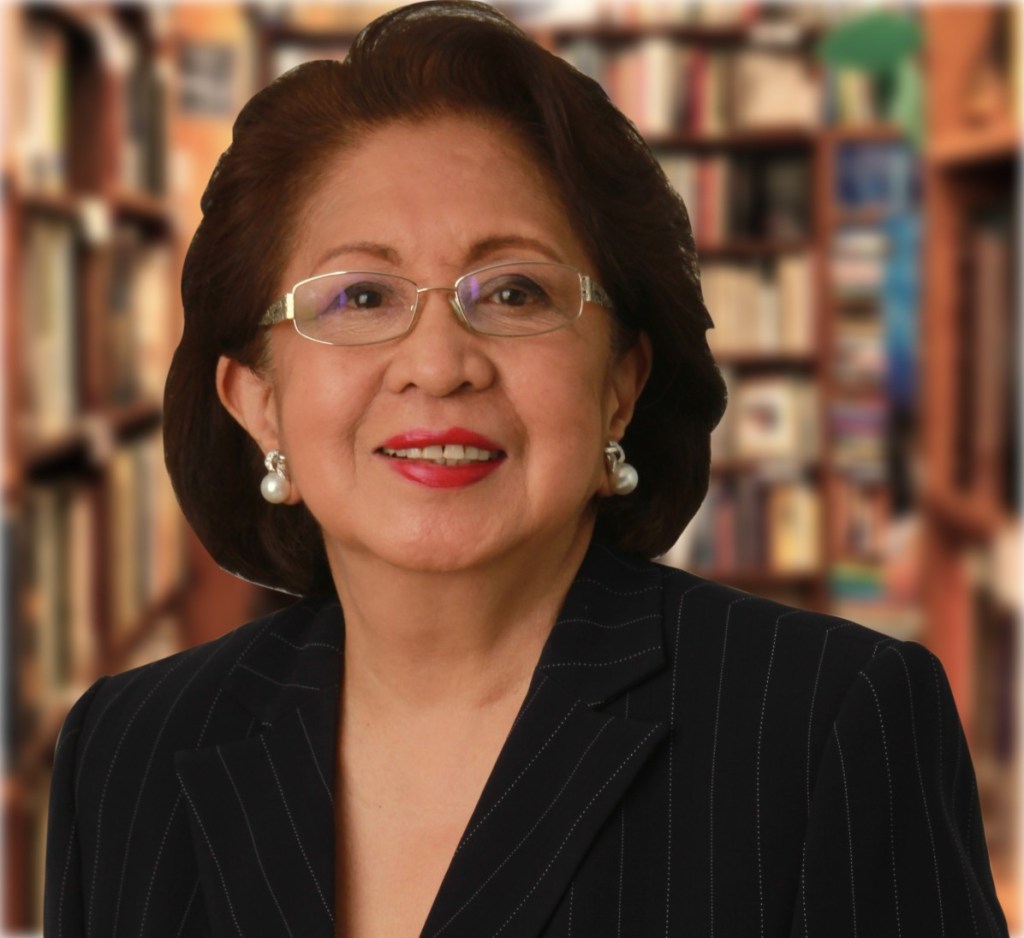

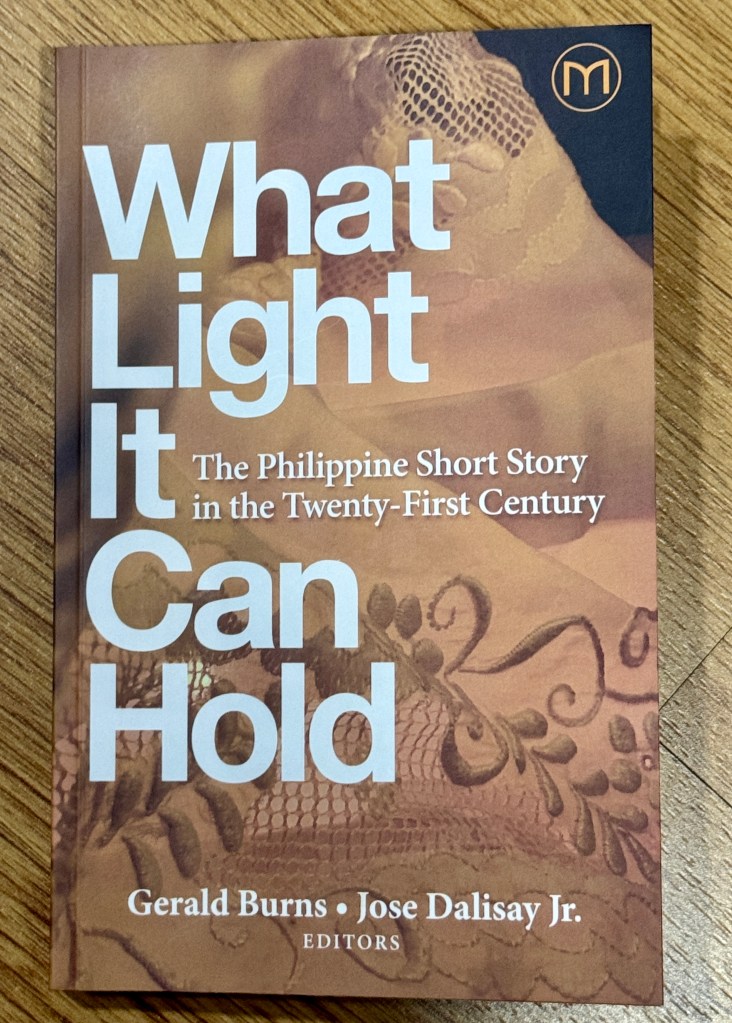

IT WON’T officially be out for another couple of weeks, but I’m happy to announce the publication of my latest book, the biography of one of the Philippine judiciary’s most fearless and remarkable women, former Supreme Court Justice and Ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales. Begun during the pandemic, Neither Fear Nor Favor: The Life and Legacy of Conchita Carpio Morales (Milflores, 2025) traces the journey of a probinsyanafrom Paoay, Ilocos Norte to the country’s highest court, followed by an even more distinguished period of service as “the people’s agent” at the Office of the Ombudsman.

I’ve written a number of biographies of outstanding Filipinos before—among them the accounting titan Washington SyCip, former UP and Senate President Edgardo Angara, and the renowned economist Leonides Virata, as well as the revolutionary Lava brothers—but this was different in many ways.

Foremostly, it was because my subject was a woman working her way up a heavily male-dominated system, constantly challenged to adhere to her fundamental values and principles in an environment of corruption, intimidation, and political accommodation. For the men—given that they had the talent and the grit, and possibly the right connections—success was practically a given; for such women as Conchita, proving oneself worthy was often doubly difficult.

Since the Supreme Court of the Philippines was established in 1901, almost 200 justices have been appointed to that exalted bench; only 18 have been women as of 2023, and it wasn’t until 1973 that the first female justice, Cecilia Muñoz Palma, took office. After Morales was appointed to the SC by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo in 2002, among the first cases to fall on her lap was the impeachment of no less than Chief Justice Hilario Davide, brought on by pro-Estrada congressmen who believed Davide had misused the Judiciary Development Fund. A fellow Justice approached the novice to ask her pointblank, “Chit, do you think you can handle this?” Inhibiting herself from the case would have been the prudent option, but she took it on, and wrote the decision disposing of the complaint.

She would soon be known for her fierce independence. Despite death threats—a grenade was once left outside her Muntinlupa home, along with a threatening message—she worshiped no sacred cows, spared no one from judicial scrutiny when the situation demanded. This was even much clearer when she retired from the Supreme Court and was appointed Ombudsman, in charge of investigating and prosecuting high-profile cases of graft and corruption in government. Among the cases that crossed her desk were those against PGMA, President Noynoy Aquino, former Senate President Juan Ponce Enrile, and former Vice President Jejomar Binay.

While most of a Justice’s or Ombudsman’s work is done quietly, away from public view, occasionally they come into the limelight even against their wishes because of our fraught political environment where issues often end up in court. One such case was the 2011 impeachment of Chief Justice Renato Corona, a highly significant and contentious case that centered on serious allegations of corruption and betrayal of public trust.

Then the Ombudsman, Morales engaged a former Supreme Court colleague, Serafin Cuevas, in what came to be known as the “battle of retired justices. “I had been summoned as a hostile witness by the defense,” Conchita recalls. “I sensed that the defense wanted to embarrass and humiliate me even. They thought that my alleged opinion that Corona had millions of dollars in undeclared deposits had been based on the three complaints filed before the Office of the Ombudsman. But it was the Anti-Money Laundering Council that had furnished me with the CJ’s record of bank transactions. I had requested their assistance as reported by the media even before I was summoned to testify. The three complaints filed at the OMB never mentioned any dollar deposits. If the defense counsels had been insightful enough, they should have figured that out.” Corona was eventually impeached on a vote of 20-3.

Her confrontations with former President Rodrigo Duterte—a distant relative, through the marriage of her nephew Manases Carpio to presidential daughter Sara—were also the stuff of theater. At the 2016 wedding of Manases’ brother Waldo, the President and the Ombudsman walked down the aisle together arm in arm—he in a cream barong and she in a bottle-green gown—and appeared friendly, making small talk. The cordiality would not last long.

One year later, in October 2017, President Duterte challenged Conchita to resign as Ombudsman, claiming that she had exercised “selective justice” in asking her deputy, Arthur Carandang, to investigate his unexplained wealth. Duterte suspended Carandang, and threatened to impeach Conchita. “Resign now,” he told Morales, “at kung hindi, huhubaran kita!” The last line—which literally translates into “or else I’ll strip you naked”—was egregiously coarse, but came as no surprise to audiences familiar by this time with Duterte’s tough-guy and often misogynistic language.

Morales promptly hit back, vowing not to be intimidated. “If the President has nothing to hide, he has nothing to fear,” she coolly told a press conference.

What most people never saw was Conchita’s lighter side. The first time she went to Broadway in 1981, she watched Evita with her sister Vicky. Before watching, they had dinner at Gallagher’s, where the size of the steaks made Conchita’s eyes pop. She couldn’t finish her portion and, ever the Ilocana, wanted to have it wrapped to take home. Her sister told her not to do that, so Conchita went to the ladies’ room, got some tissue paper, and wrapped the steak. The following day, they went to Washington, where they went to dinner and had shrimp cocktail. Conchita then took out the previous day’s steak to the shock of Vicky, who said, “Don’t bring that out. Don’t embarrass me!” The steak ended up in the wastebasket.

Lawyer Ephyro Amatong and others who trained with her were privy to Conchita’s moods and modes. “When she was in her ‘Justice’ mode, she was very strict, very sharp, very hard to read, with an incredible poker face. I knew lawyers like the co-head of litigation at a big firm who thought that she was scary,” Eph says. “But while she could be reserved, she could also be very charming and accommodating. She had a great sense of humor. I remember when she had to attend an en banc meeting or when she had a ponencia for deliberation, just before she went out the door, she might be laughing or making jokes about the grilling she might get, or mention what she was wearing and how fashionable she was. But once the door opened and once she stepped out, her ‘Justice’ face came on, ready for battle.”

You can read more about this feisty Filipina, the Ramon Magsaysay awardee for public service in 2016, in the book. Neither Fear Nor Favor: The Life and Legacy of Conchita Carpio Morales will be available on Shopee and Lazada or from milflorespublishing.com very soon.