Penman for Monday, June 8, 2015

TWICE OVER the past three months, I’ve been giving workshops to medium-sized groups of people in my general age range (let’s put that at 50 to 70), people who came together because they had stories to tell, but needed some guidance on how to tell them. These workshops were arranged by the publisher and writer Marily Orosa, who had come up with very engaging book ideas to which these potential writers could contribute, and who thought that it would be a good idea to have a practicing writer give them a bit of coaching before they plunged into the actual task of writing.

I was glad that Marily put these workshops together, first because I’ve always believed that every person has at least one good story in him or her, and that it’s my job as a writing teacher to get that story out of the person. Second, being a senior myself, I’m happy when older people get an opportunity to express themselves in this obsessively youth-centered world.

Many if not most members of my audience were retirees or approaching retirement after many decades of productive work in their professions. One was a former Cabinet secretary and another a university president, among other luminaries, but in the end, it wasn’t one’s position that mattered as much as one’s experiences, which seniors have in spades.

I couldn’t cram a semester’s worth of lessons into a Saturday afternoon, but I did what I could to give them a framework, an approach, and some tools with which to get their stories out of their memories and onto the digital page. First, we talked about the basic difference between life (their life experience, the raw material) and art (the finished product they were expected to come up with).

What do artists—writers, painters, musicians, and so on—do to and with their materials to make works of art? What do artists see in the things around them that most other people don’t? In this way, we try to get people to see their own lives and experiences as matter to be structured and shaped—not to distort the truth (the object, I think, of all honest art) but precisely to get at it and to bring it out, even if it may not always be pleasant—and indeed much art out there is meant to disturb.

We talk about selection, and how the writer or artist chooses material to use directly in the artwork (the text) and leaves other things out (the context), given that you can’t possibly use everything out there. We talk about how artists work with concrete images and objects to suggest ideas, rather than the grand abstractions that, say, editorial writers and philosophers use.

When we consider life experiences, we then talk about distances in space and time, and about physical and emotional distance. Many participants at these workshops, for example, want to talk about travels they undertook to interesting places, and what I try to do is to get them to write something beyond the verbal equivalent of a posed snapshot in front of the Eiffel Tower or the Golden Gate. A trip to Paris isn’t just ever about Paris, but also, implicitly, about Tagbilaran or Bayombong, wherever it was the narrator or protagonist came from, and it’s that perspective that makes this particular experience of Paris unique.

Writing about the past really involves two protagonists (taking a page from Thomas Larson): the remembered self and the remembering self. Writing about a journey involves not just traversing physical territory, but also that internal space within which the character grows—so the physical journey is always paralleled by an internal, often spiritual, one.

After clarifying these fundamental concepts, I then introduce them to some basic tools of the trade—the elements of fiction which, when carried over to nonfiction, liven up the narrative and make both writing and reading a more engaging experience. We talk about plot, character, theme, point of view, dialogue, description, and setting—how to employ time, how to bring scenes to life, what to say and what to leave out.

I remind them what a lonely and (for most people) unremunerative occupation writing is, but going beyond the money or the lack of it, how important it is to write one’s stories down before the memory deserts or defeats us. It’s especially important for the young to know about how their elders lived and thought. It might take them another 20 years to become receptive readers, but the record will be there, and they’ll be surprised to find, as we ourselves did, how the past anticipated the future in so many ways.

I feel drained at the end of these three-hour workshops, faced with a flood of eager questions, but I also feel elated by all the creative energy I seem to have unleashed among my fellow seniors, and I can only begin to imagine what a touch of art can do to that rich lode of memories lying deep in their many-chambered brains.

AND NOW’s as good a time as any to draw attention to the good work done by Marily Orosa’s Studio 5 Designs, which has been in the business of producing not just books but prizewinning ones, lauded both for their design and their substance. I’ve had the pleasure of working with Marily on a couple of coffeetable book projects, most notably De La Salle University’s centennial volume, The Future Begins Here, which I edited and wrote for, and which won a Quill and an Anvil Award (the Quill, Anvil, and National Book Awards are the local publishing and PR industry’s measures of excellence).

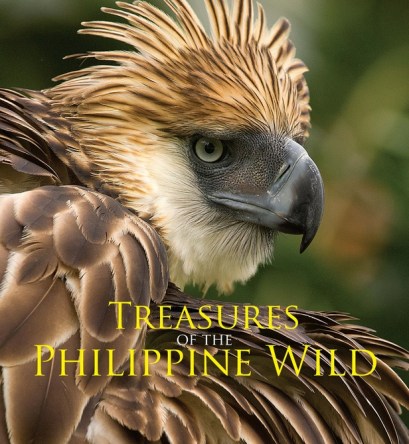

Studio 5 has also won NBAs for In Excelsis (The Martyrdom of Jose Rizal) by Felice P. Sta. Maria and The Tragedy of the Revolution (The Life of Andres Bonifacio) by Adrian Cristobal. Malacañan Palace (The Official Illustrated History) by Manuel Quezon III and Jeremy Barns also won a host of local and international awards, as did the magnificent Treasures of the Philippine Wild. Freundschaft/Pagkakaibigan (celebrating 60 years of friendship between Germany and the Philippines) will be included in the prestigious international design annual, Graphis.

Beyond being visual treats, these are all significant books, and their creators and publisher deserve high praise and encouragement.

Penman for Monday, September 1, 2014

Penman for Monday, September 1, 2014