Penman for Monday, July 29, 2019

I’M SURE I’m not alone in having some fun tracking the online art auctions held regularly by the Leon and Salcedo houses, if only to daydream about the often fascinating artworks crossing the block. Now and then I dabble in a bit of buying and selling—a chair here, a book there—but mostly I’m a kibitzer enjoying the action from the sidelines.

What I do come away with, even just by poring over the auction catalogues (which themselves will very soon become collectible), is an ongoing education in Philippine art. Going beyond the peso signs, learning about our painters and sculptors and the stories behind specific artworks is a reward unto itself, especially given how the arts media today—driven and sometimes threatened by advertising and PR—devote precious little attention and space to historical subjects.

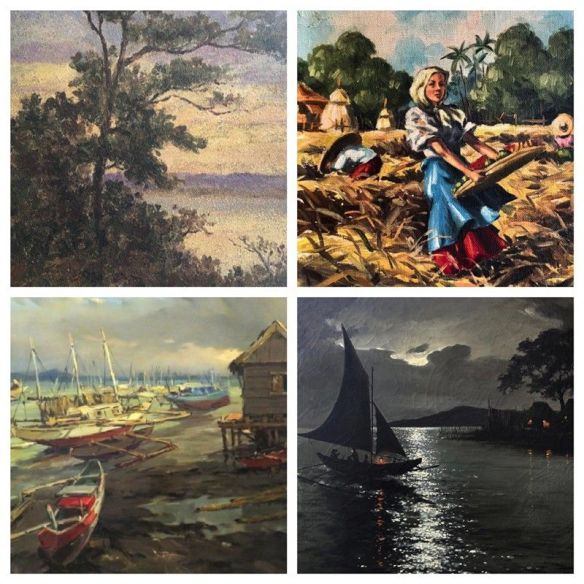

I love discovering (or rediscovering, since they were already well known to others) masters I never knew about, like Lorenzo Guerrero, Felix Martinez, Isidro Ancheta, and Jorge Pineda—most of them, not incidentally, painters of the kind of traditional, romantic Filipino landscape I personally prefer, as they give me comfort and peace of mind and spirit in my old age. Among their successors who figure prominently in my small collection are Gabriel Custodio (see below) and Elias Laxa, whose pieces I can never tire of looking at across a room.

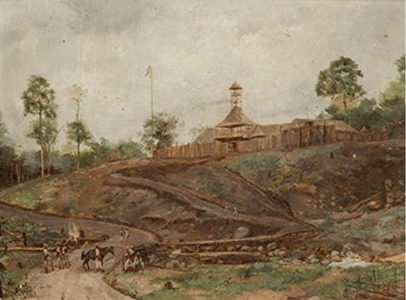

For example, just last month, a Spanish auction house featured two remarkable paintings of Marawi by the Spanish soldier and painter Jose Taviel de Andrade (1857-1910), who at one time was assigned to watch over (and perhaps spy on) Jose Rizal in 1887 but who later became his friend, and whose brother Luis served as Rizal’s defense counsel at his trial. The Andrade paintings depict Spanish fortifications and a bridge from the campaign against the Muslim resistance in Marawi—and if not for the auction brief, I would never have learned about and looked up this story of an improbable friendship, and about that campaign. (The two Andrade paintings opened at 8,000 euros and sold for 32,000—way above my pay scale!)

Yet another painter I just recently came to know about was Anselmo Espiritu, whose name and work I was alerted to by an online acquaintance named Wassily Clavecillas, who shares my interest in old books and artworks. Drawing on some scant references to Espiritu from various books and sources, Wassily introduced me to the fact that Anselmo—whose birthdate remains unknown, but who reportedly died in 1918—was a student of Lorenzo Guerrero, along with his brother Manuel (among Guerrero’s other students was Juan Luna). I’ll let Wassily narrate the rest of the story, slightly paraphrased by me:

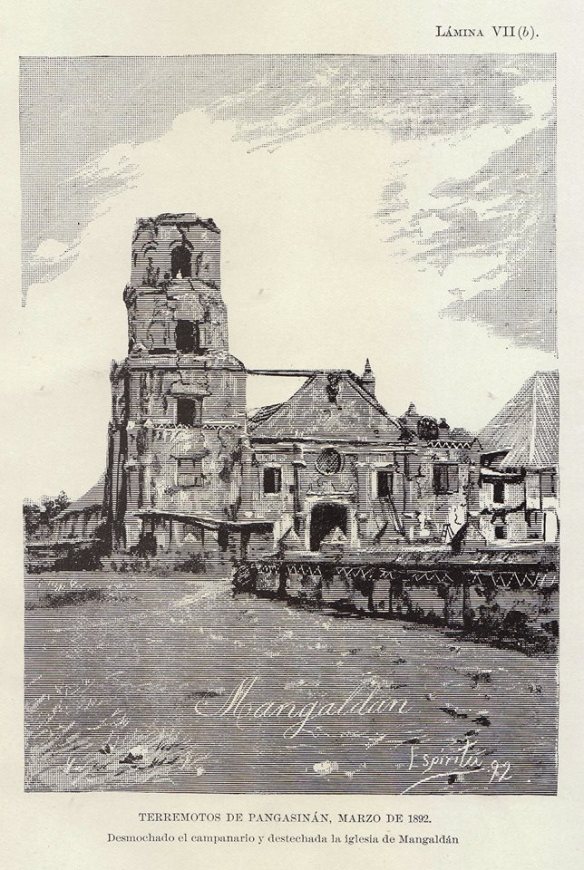

“According to my research, Anselmo Espiritu was once commissioned by the Observatorio de Manila, then managed by Padre Federico Faura, SJ. In 1892 a great earthquake struck Luzon, decimating churches in Pangasinan. The Observatorio commissioned Anselmo to make paintings of the devastated churches, after which he then made serigraphs or silkscreen prints of those same paintings. Sadly the original paintings and their silkscreen versions perished along with the observatory itself during the Second World War, and the only copies of Espiritu’s depictions of the earthquake’s ravages in Pangasinan, as far as I know, have come down to us in the form of offset prints.” (Wassily has a few of these prints, and sent me digitized copies.)

He raised another interesting question: “One also has to ask why the Observatorio and Padre Faura chose to commission Espiritu to do paintings of the devastated churches when photography was already available and even possibly affordable at that time. Why go through the effort of hiring a painter when photos were more accurate down to the minutest detail? Was it an aesthetic decision, in the way that the engravings in Alfred Marche’s book on Luzon and Palawan are prime examples of the engraver’s art?”

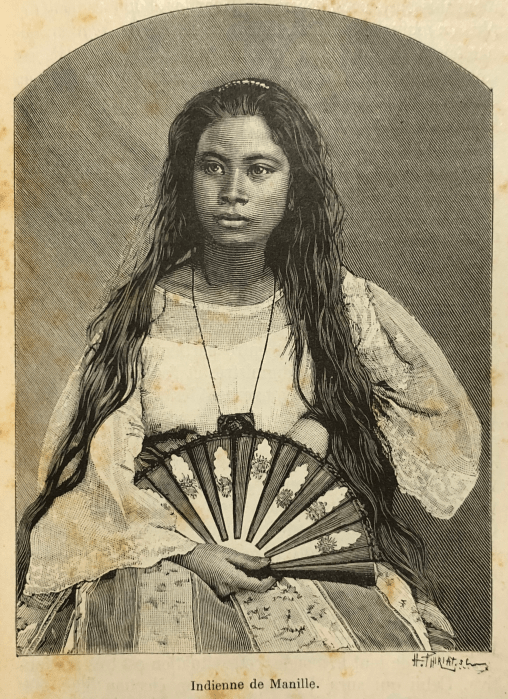

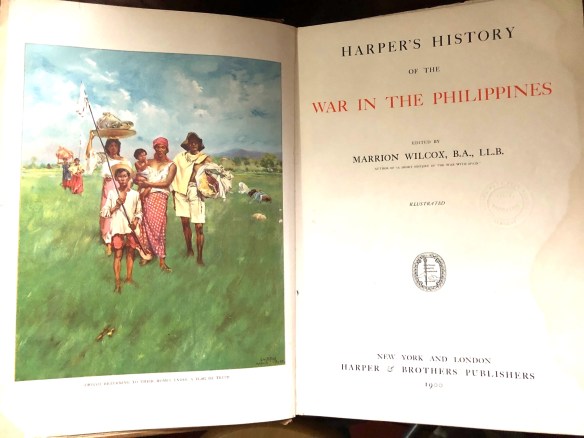

He was, of course, referring to Voyage aux Philippines, which the French naturalist and explorer published in 1887 after six years of traipsing around Tayabas, Catanduanes, Marinduque, and Palawan, among other places. I was lucky to acquire a copy of the original Hachette edition a few years ago, which will take me time to digest, as it’s in French (thankfully, an English translation is also available), but the illustrations (like the one below) are indeed exquisite, tending to support Wassily’s conjecture that an artist’s hand can often be more evocative than a photographer’s eye.

Espiritu would go on from that commission to become a celebrated painter in his own right, winning medals for his works at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, where the likes of Juan Luna, Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, Fabian de la Rosa, Juan Arellano, and Isidro Ancheta also exhibited. His nephew Oscar (1895-1960) also became an established painter.

Two paintings of barrio scenes by Espiritu sold last month at a Leon Gallery auction for substantially higher than their opening bids. They came out of a private collection in Spain—or I should say, came home, which is one great service these auctions perform, even as newer Filipino artworks now cross the seas with the growing and well-deserved popularity of Philippine art. I’m happy just to watch this majestic traffic go by.

Penman for Monday, May 20, 2019

Penman for Monday, May 20, 2019